“The Transformation of Io into a Heyfer” (III) – Ovid

a cow

poets can be confounding

least Western, faith communities

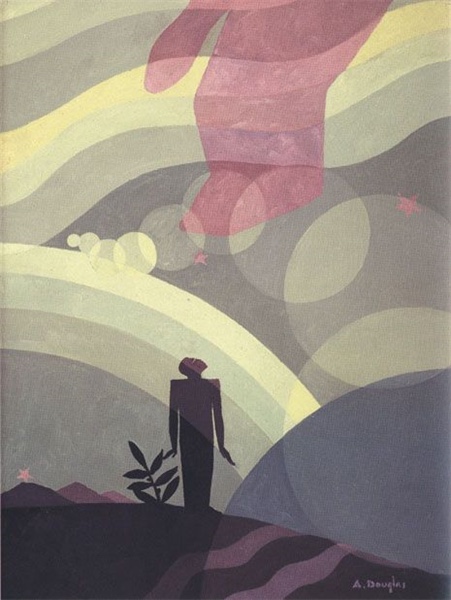

“The Siver Age“ (c.1516)

Then land-marks limited to each his right:

For all before was common as the light.

Nor was the ground alone requir’d to bear

Her annual income to the crooked share,

But greedy mortals, rummaging her store,

Digg’d from her entrails first the precious oar;

Which next to Hell, the prudent Gods had laid;

And that alluring ill, to sight display’d.

Thus cursed steel, and more accursed gold,

Gave mischief birth, and made that mischief bold:

And double death did wretched Man invade,

By steel assaulted, and by gold betray’d,

Now (brandish’d weapons glittering in their hands)

Mankind is broken loose from moral bands;

No rights of hospitality remain:

The guest, by him who harbour’d him, is slain,

The son-in-law pursues the father’s life;

The wife her husband murders, he the wife.

The step-dame poyson for the son prepares;

The son inquires into his father’s years.

Faith flies, and piety in exile mourns;

And justice, here opprest, to Heav’n returns.

“The Golden Age“ (1637)

The golden age was first; when Man yet new,

No rule but uncorrupted reason knew:

And, with a native bent, did good pursue.

Unforc’d by punishment, un-aw’d by fear,

His words were simple, and his soul sincere;

Needless was written law, where none opprest:

The law of Man was written in his breast:

No suppliant crowds before the judge appear’d,

No court erected yet, nor cause was heard:

But all was safe, for conscience was their guard.

The mountain-trees in distant prospect please,

E’re yet the pine descended to the seas:

E’re sails were spread, new oceans to explore:

And happy mortals, unconcern’d for more,

Confin’d their wishes to their native shore.

No walls were yet; nor fence, nor mote, nor mound,

Nor drum was heard, nor trumpet’s angry sound:

Nor swords were forg’d; but void of care and crime,

The soft creation slept away their time.

The teeming Earth, yet guiltless of the plough,

And unprovok’d, did fruitful stores allow:

Content with food, which Nature freely bred,

On wildings and on strawberries they fed;

Cornels and bramble-berries gave the rest,

And falling acorns furnish’d out a feast.

The flow’rs unsown, in fields and meadows reign’d:

And Western winds immortal spring maintain’d.

In following years, the bearded corn ensu’d

From Earth unask’d, nor was that Earth renew’d.

From veins of vallies, milk and nectar broke;

And honey sweating through the pores of oak.

way more fun than the Bible

Richard

___________

High o’er the clouds, and empty realms of wind,

The God a clearer space for Heav’n design’d;

Where fields of light, and liquid aether flow;

Purg’d from the pondrous dregs of Earth below.

Scarce had the Pow’r distinguish’d these, when streight

The stars, no longer overlaid with weight,

Exert their heads, from underneath the mass;

And upward shoot, and kindle as they pass,

And with diffusive light adorn their heav’nly place.

Then, every void of Nature to supply,

With forms of Gods he fills the vacant sky:

New herds of beasts he sends, the plains to share:

New colonies of birds, to people air:

And to their oozy beds, the finny fish repair.

A creature of a more exalted kind

Was wanting yet, and then was Man design’d:

Conscious of thought, of more capacious breast,

For empire form’d, and fit to rule the rest:

Whether with particles of heav’nly fire

The God of Nature did his soul inspire,

Or Earth, but new divided from the sky,

And, pliant, still retain’d th’ aetherial energy:

Which wise Prometheus temper’d into paste,

And, mixt with living streams, the godlike image cast.

Thus, while the mute creation downward bend

Their sight, and to their earthly mother tend,

Man looks aloft; and with erected eyes

Beholds his own hereditary skies.

From such rude principles our form began;

And earth was metamorphos’d into Man.

though I’d been reading a not unaccomplished version of Ovid‘s “Metamorphoses“, thrilling already at much of it, for the sake of comparison I happened upon this other utter masterpiece

the pedigree is impeccable, an array of the most illustrious English poets of the eighteenth century in concert around a mighty translation of one of poetry’s crowning works, Sir Samuel Garth, John Dryden, Alexander Pope, Joseph Addison, William Congreve, “and other eminent hands”, according to the web page, do the work, and it is masterly

read on, from the very first book of fifteen, its beginning, its genesis

Richard

____________________________

The Creation of the World

Of bodies chang’d to various forms, I sing:

Ye Gods, from whom these miracles did spring,

Inspire my numbers with coelestial heat;

‘Till I my long laborious work compleat:

And add perpetual tenour to my rhimes,

Deduc’d from Nature’s birth, to Caesar’s times.

Before the seas, and this terrestrial ball,

And Heav’n’s high canopy, that covers all,

One was the face of Nature; if a face:

Rather a rude and indigested mass:

A lifeless lump, unfashion’d, and unfram’d,

Of jarring seeds; and justly Chaos nam’d.

No sun was lighted up, the world to view;

No moon did yet her blunted horns renew:

Nor yet was Earth suspended in the sky,

Nor pois’d, did on her own foundations lye:

Nor seas about the shores their arms had thrown;

But earth, and air, and water, were in one.

Thus air was void of light, and earth unstable,

And water’s dark abyss unnavigable.

No certain form on any was imprest;

All were confus’d, and each disturb’d the rest.

For hot and cold were in one body fixt;

And soft with hard, and light with heavy mixt.

But God, or Nature, while they thus contend,

To these intestine discords put an end:

Then earth from air, and seas from earth were driv’n,

And grosser air sunk from aetherial Heav’n.

Thus disembroil’d, they take their proper place;

The next of kin, contiguously embrace;

And foes are sunder’d, by a larger space.

The force of fire ascended first on high,

And took its dwelling in the vaulted sky:

Then air succeeds, in lightness next to fire;

Whose atoms from unactive earth retire.

Earth sinks beneath, and draws a num’rous throng

Of pondrous, thick, unwieldy seeds along.

About her coasts, unruly waters roar;

And rising, on a ridge, insult the shore.

Thus when the God, whatever God was he,

Had form’d the whole, and made the parts agree,

That no unequal portions might be found,

He moulded Earth into a spacious round:

Then with a breath, he gave the winds to blow;

And bad the congregated waters flow.

He adds the running springs, and standing lakes;

And bounding banks for winding rivers makes.

Some part, in Earth are swallow’d up, the most

In ample oceans, disembogu’d, are lost.

He shades the woods, the vallies he restrains

With rocky mountains, and extends the plains.

And as five zones th’ aetherial regions bind,

Five, correspondent, are to Earth assign’d:

The sun with rays, directly darting down,

Fires all beneath, and fries the middle zone:

The two beneath the distant poles, complain

Of endless winter, and perpetual rain.

Betwixt th’ extreams, two happier climates hold

The temper that partakes of hot, and cold.

The fields of liquid air, inclosing all,

Surround the compass of this earthly ball:

The lighter parts lye next the fires above;

The grosser near the watry surface move:

Thick clouds are spread, and storms engender there,

And thunder’s voice, which wretched mortals fear,

And winds that on their wings cold winter bear.

Nor were those blustring brethren left at large,

On seas, and shores, their fury to discharge:

Bound as they are, and circumscrib’d in place,

They rend the world, resistless, where they pass;

And mighty marks of mischief leave behind;

Such is the rage of their tempestuous kind.

First Eurus to the rising morn is sent

(The regions of the balmy continent);

And Eastern realms, where early Persians run,

To greet the blest appearance of the sun.

Westward, the wanton Zephyr wings his flight;

Pleas’d with the remnants of departing light:

Fierce Boreas, with his off-spring, issues forth

T’ invade the frozen waggon of the North.

While frowning Auster seeks the Southern sphere;

And rots, with endless rain, th’ unwholsom year.

High o’er the clouds, and empty realms of wind,

The God a clearer space for Heav’n design’d;

Where fields of light, and liquid aether flow;

Purg’d from the pondrous dregs of Earth below.

Scarce had the Pow’r distinguish’d these, when streight

The stars, no longer overlaid with weight,

Exert their heads, from underneath the mass;

And upward shoot, and kindle as they pass,

And with diffusive light adorn their heav’nly place.

Then, every void of Nature to supply,

With forms of Gods he fills the vacant sky:

New herds of beasts he sends, the plains to share:

New colonies of birds, to people air:

And to their oozy beds, the finny fish repair.

A creature of a more exalted kind

Was wanting yet, and then was Man design’d:

Conscious of thought, of more capacious breast,

For empire form’d, and fit to rule the rest:

Whether with particles of heav’nly fire

The God of Nature did his soul inspire,

Or Earth, but new divided from the sky,

And, pliant, still retain’d th’ aetherial energy:

Which wise Prometheus temper’d into paste,

And, mixt with living streams, the godlike image cast.

Thus, while the mute creation downward bend

Their sight, and to their earthly mother tend,

Man looks aloft; and with erected eyes

Beholds his own hereditary skies.

From such rude principles our form began;

And earth was metamorphos’d into Man.

_______________________________