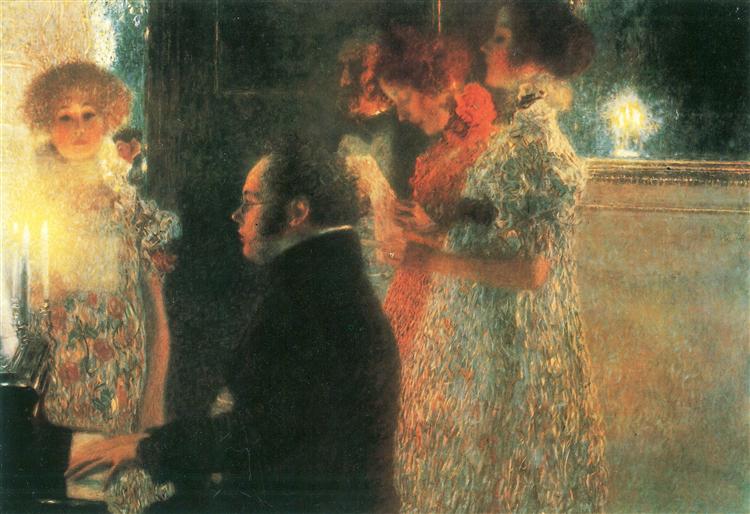

D 894, October, 1826, Schubert would’ve

known he was about to die, he was 29,

he would die two years later, November,

1828, you can hear it, his encounter with

Heaven

this is not merely entertainment, this is

contemplation, a description of what he’s

seen at the Celestial Gates, you can

actually hear the stars twinkle in their

great expanse of infinity from the very

first movement

later, dance rhythms suggest an embrace,

an embrace as a symbol of acknowledgment,

acquiescence, acceptance, welcome, into

the Beyond, whatever you might want to

call it

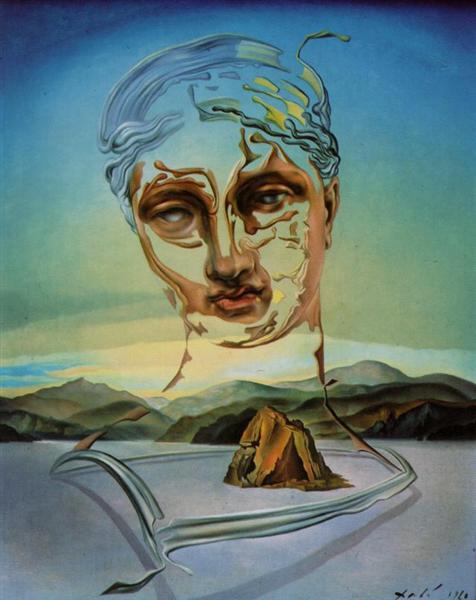

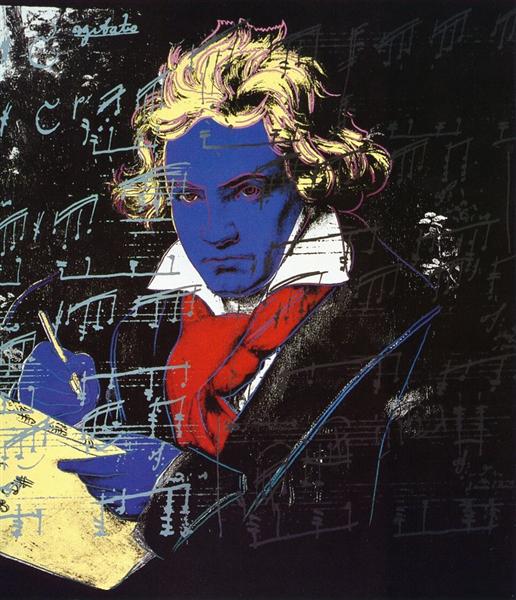

Beethoven confronts God, Schubert describes

his personal death experience

but that’s not one, but a couple of other stories

R ! chard