November / Month of the Sonata – 20

“Rhapsody of Steel“ (1959)

________

so what’s a rhapsody

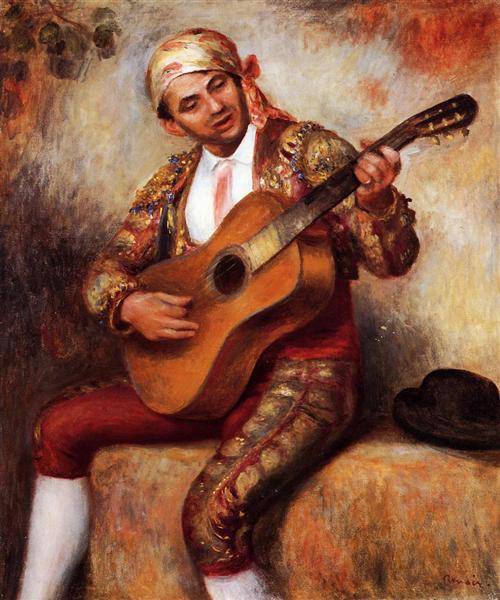

Cyprien Katsaris

________

if there’s only one concert you see

this week – I would’ve said this year

but I have way too many irresistible

concerts to promote – make it this

one, like none I’ve ever seen before,

Cyprien Katsaris, who wowed us in

my last encomium, delivers, not one,

but two concertos, when emotionally

I can usually deal with only one

but you can pause between the pieces,

like I did, to wipe a tear or two away

after the adagios, which remind me,

always, of my beloved, John

but that’s another story

Katsaris starts with an improvisation,

which he elucidates as an art form

much more expertly than I would,

then delivers a stunning rendition of

his mastery of that gift

though I couldn’t identify the first part

of it, the melting melody in the last

section of his homage to, essentially,

the Romantic Period, rushed back

memories for me of a piece I could

never forget, the music from Fellini’s

heartbreaking masterpiece “La Strada“

– listen, listen – right out of Romantic

Period idioms, its very story even, like

Dickens’ “Oliver Twist“, his Little Nell

from the “The Old Curiosity Shop“,

staples of my adolescence, married

to a nearly mythic lyrical invention

let me add that improvisations have

been an integral part of concertos for

a very long time, the cadenzas, an

interpolation by the performing artist,

hir riff, a strutting of hir stuff, late

in the, usually final, movement, a

consequence, incidentally, of the

more forward, individualistic,

18th-Century progression towards

individual rights, some left to the

performing artist, but many

prescribed by the composer himself,

where, here, I must, gender sensitive

myself, unceremoniously interject to

explain my deference to the

designation above, “himself“, to male

merely composers, who were then the

only ones, however culturally ignobly,

to nevertheless shape our quite, I

think, extraordinary musical trajectory,

for better, of course, or for worse

in this instance, I suspect Katsaris

wrote his own cadenzas for the

Mozart, notice his arm at the end of

the first movement fly up in an

especial transport, and in the last

movement, watch his very

exuberance mark the spot, but I

couldn’t put it past Mozart to have

written something so historically

visionary

Bach, incidentally, wasn’t doing

cadenzas, so don’t look for them

the two concertos that follow the

improvisation, Bach’s, my favourite

of his – you’ll understand why when

you hear it – then Mozart’s 21st –

everyone’s favourite – are both

played transcendentally

consider the difference in period,

the earlier Baroque, with Bach’s

notes skipping along inexorably,

the pace required by the

harpsichord, which didn’t have

hold pedals to allow notes to

resonate, the music moves along

therefore nearly minimalistic tracks,

a pace, and musical motif, that don’t

stop, they keep on chugging, until

they reach their destination, their,

as it were, station, or even their

stasis

Mozart’s music is as effervescent,

but conforms to a different cadence,

where a theme is presented, then a

musical, and contrasting, second,

with recapitulation, sometimes

merely partial, which is to say that

the call and response dynamic of

the dance, or for that matter, by

extension, modern ballads, is

being established, codified, and

elucidated

an era has intervened

then as an encore, Katsaris delivers,

not a cream puff, but Liszt, of all

people, we’re used to performers

giving us trifles at this point, but not

Katsaris

then to top it all off, he plays the Chopin

you thought you’d never ever hear again,

but here immaculate and utterly

inspirational

the orchestra alone performs after the

intermission, works by Ravel and Bizet,

surprisingly similar, I thought, the two

composers, in their musical idiom, the

use of the winds as metaphors, for

instance, for originality, eccentricity,

unmitigated poetry within the context

of what is not unnatural

neither is either composer adverse to

atonality, they work in textures, instead

of melodies, all of which is very

Impressionistic, see of course Monet

and others for historical reference

did I say I want to be Cyprien Katsaris

when I grow up, well there, it’s said,

he’s lovely

R ! chard

__________

if I haven’t spoken much about Bach

until now it’s that, although he is at

the very start of our modern music,

having in fact set up its very alphabet,

the scale we’ve been using since, he

is nevertheless as different from our

own era in music as Shakespeare is

to us in literature, both are stalwarts,

but we no longer say, for instance,

thee or thou, nor write in iambic

pentameter, nor do we dance

gavottes at court, nor congregate

at church to hear cantatas

the turning point is the Enlightenment,

also called the Age of Reason, when

the concept of God was being

questioned, if not even debunked, and

the mysteries of nature were being

rationally resolved, handing authority

to knowledgeable individuals instead

of to popes

by the time of Mozart and Haydn, a

secular tone was gradually pervading

all of the arts, devoid of any religious

intentions, sponsors were private

rather than clerical

Bach had indeed been hired by a prince,

Leopold of Anhalt-Köthen, but was

appointed court musician at his ducal

chapel, Nikolaus l, Prince Esterházy

wanted Haydn’s music, rather, for his

court entertainment, and for himself

as well, incidentally, as a fellow baryton

player

Mozart was also employed by a prince,

but left when he wasn’t being payed

well

times haven’t changed much, see

Trump, for instance

after the French Revolution, there was

not much call for religious music,

human rights took the place of God,

liberté, égalité, fraternité, and all that,

not to mention the American Bill of

Rights, and that’s the route we’ve

been following ever since, for better

or for worse

but hey, we’re still reading Shakespeare,

and still listening to Bach, and loving

both of them, some of us

here’s some more Bach for old times’

sake, his Partita no 2 for solo violin

a partita is just a series of dance suites

– an allemande, a courante, a sarabande,

a gigue, and a chaconne, in this case – I

don’t think anyone other than Bach ever

wrote some, but his are sublime

it’s kind of like my calling my own

stuff prosetry, for whatever infinity

that word might ever deliver, though

no one else might ever use that term

again

listen also to a transposition of its

celebrated last movement, the

Chaconne, for left-hand piano, in

this instance, as transposed by

Brahms, a precursor to Ravel’s

Concerto in G major for the Left

Hand, written for Paul

Wittgenstein, an already

accomplished pianist – the much

more famous philosopher,

Ludwig‘s, brother – who’d lost his

right hand during the First World

War, and who’d hopefully be

inspired, by such positive

reinforcement

art, music, poetry thrives on such

heartfelt expressions of sympathy,

compassion, communion

art is the faith that we rely on now

that God/dess is gone

R ! chard

“Leningrad in blockade. Sketch on the theme of

“Leningrad Symphony” of D. D. Shostakovich.“

(c.1943)

__________

though I’ve been through the Seventh

three times already, consecutively, it

doesn’t reach, for me, the heights the

Fifth did, its first movement is

manifestly imperious, nearly even

overwhelming, certainly unforgettable,

I’ve been humming the ostinato in my

sleep

but the following movements seem to

me – not being Russian, nor having as

intimately incorporated their culture,

where rhythms and history are

inextricably intertwined – muddled

about the reconstruction of its

shattered world, melodies might be

lovely but are lost in a blur of musical

directions, there isn’t enough repetition

of musical motifs to find solid ground,

angry statements follow lyrical adagios

too often to get our bearings on what

might be going on

the first movement, however, remains a

triumph, note the debt owed to Ravel’s

“Bolero“ in the rousing ostinato, the

part where the same musical phrase

obstinately repeats its peremptory and

ever more vociferous mantra, its

headlong incantation, an interesting

blend in either symphonic work of the

sinuous, the seductive, the beguiling,

turning into the overtly martial, all to

do with pulse

the Symphony no 7, the “Leningrad”,

was first presented in that very city

during its siege by the Germans,

which lasted from 1941 to 1944,

however unbelievably, Shostakovich,

already a giant, was expected to deliver

a masterpiece by both the people and

by the regime, imagine Bono doing a

concert for Syria

Shostakovich doesn’t disappoint

players were culled from what remained

of instrumentalists among the survivors

of both Stalin’s criminal purges and of

the German siege itself left in the city,

those who hadn’t survived the famine

there, Valery Gergiev, an exalted

Russian conductor, describes them as

walking skeletons, meagre from

starvation, we’ve seen these before at

Auschwitz

the world heard, and was moved,

imperialism in any form was being

vociferously condemned, going back

to Napoleon even and his own failed

invasion, if not also to Hannibal

crossing the Alps, Caesar, his

Rubicon

much of this symphony is about cultural

resistance, the survival of a proud and

resilient seed, any proud and resilient

seed, hence its international standing

see Beethoven’s 9th Symphony for

comparable fanfare, flourish, and

circumstance, the only other work of

any such historical political importance

and, appreciably, still unsurpassed,

except for, maybe, Roger Waters

channeling Pink Floyd at the Berlin

Wall, along with, not incidentally

there, again Beethoven

R ! chard

psst: the other great composer of the

20th Century, Messiaen, also

composed a commemoration of

an awful moment in our history,

the Holocaust, his “Quartet for

the End of Time“, played originally

in his very concentration camp by

similarly “walking skeletons”, does

for me everything Shostakovich’s

Seventh didn’t

for my sister

a competition program that pits

youngsters against each other,

but on a variety of instruments,

with some operatic voice, has

riveted us to our sets on Friday

evenings, seven o’clock local

time throughout Canada

out of the province of Quebec,

however, and therefore in

French

“Virtuose“ lives up to its name

with extraordinary performances

from mere children, and some

adolescents, you can catch all of

the past episodes, and performers,

on their website

last week a young man delighted

us with a movement from a bassoon

sonata, an unlikely instrument, of

Saint-Saëns, his opus 168

my sister expressed surprise,

un basson, she marvelled

quickly I sought out, of course, the

full composition, it’s otherwise for

me like reading one chapter only

out of a book

it’s a short piece, no longer the

grand statements of the earlier

Romantic Period, but a series of

pastiches, fleeting impressions,

impromptu ruminations rather

than extended dissertations,

something like what I’m doing

here with these texts

you’ll recognize also a similar

approach in other composers of

the period, Debussy especially,

but too Satie, Ravel, Poulenc to

name only a few, the speed of

the new century precluded

extended musical peregrinations,

you’ll remark on the dearth of

symphonies, concertos,

composed during this epoch

the composition is in G major, my

cleaning lady had come over, was

already busy in an adjoining room

at the time, I was nearing the

end of the first movement, the

allegro moderato, a wistful

evocation of spring, I thought,

an innocent, fragile blossom

unfurling its delicate petals

with unaffected grace and

unconscious poetry

the final note sounded, the

bassoonist removed his lips from

the tube, but the note kept on

playing, coming, as I soon

understood, not from the video I

was watching, but from the other

room, Jo had turned on the

vacuum cleaner

o my god/dess, I uttered, hurried

over to where she was, subdued

my enthusiasm in order not to

unduly rattle her, as I brimmed

with my scintillating insight

your vacuum cleaner vacuums in

G, I gushed when she turned to

acknowledge me, it continued the

last note, I explained, of the first

movement of my sonata, Saint-

Saëns’ – say that three times with

a lisp, I interjected – until you

turned your vacuum cleaner off,

which is also, I pointed out, a

wind instrument

her delight was modest compared

to mine, however ever nevertheless

congenial, and quickly she returned

to her duties

I went back tickled pink to my

monitor and the following

movement, the sprightly and equally

enchanting allegro scherzando

Richard

“L’oiseau de feu“ (1910)

________

after playing Scriabin’s 4th Sonata,

in F# major, opus 30, a passionate

but poised performance of a work

dated 1903, Ravel maybe, or

Debussy, at first I thought, though

neither had ever been so furious in

my recollection, then a transcription

for piano of the last movements of

Stravinsky’s “Firebird”, a work as

obstreperous as the Scriabin, and

as revolutionary, relentless and

brash, much more audacity than

diplomacy however ultimately

treasured universally and celebrated,

Maria Mazo undertakes no less than

the mightiest of the mighty, gasp,

Beethoven’s “Hammerklavier”

she takes on the first two movements

at something of a clip, not an

unwelcome occurence so long as you

have the fingers for it, which on the

strength of her earlier numbers I

deemed she would, and did, which

only added to the gravitas of her then

largo, which thereby became

resplendent, luminous, utterly and

verily, indeed, transcendental, note

the cherubs twittering halfway

through, just before Beethoven

enters the portals of very Heaven

and is transformed into radiance and

incandescent light before your

very astonished sensibilities

Maria Mazo should win

Richard