Just another WordPress.com weblog

Category: Haydn

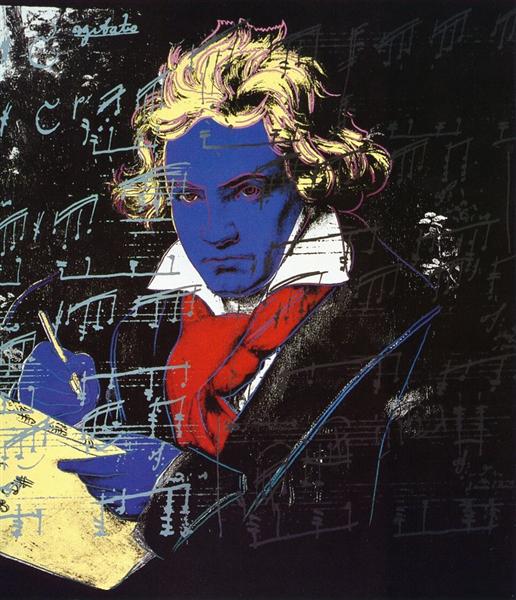

D 845, Schubert has accumulated so much

Beethoven that his Beethoven is beginning

to shine through in his own compositions,

Beethoven was a forefather, still present,

it’s often difficult to tell one, indeed, from

the other, even here

Beethoven, see above, punched through

Classicism – Mozart, Haydn – its artificiality,

delivering emotion, instinctively, from the

very start, from which he nearly

single-handedly delivered to the world no

less than Romanticism, like delivering the

recalibration of time and space after

Einstein essentially, so profound a

cultural metaphysical reorganization

Schubert remains ever more courteous,

more beholden to the upper crust that

supports him, and that he ever wants to

court, you can hear it, listen, there is no

confrontation here, just, dare I say,

entertainment

Schubert was not a revolutionary

___________

o, I said, when my flute teacher, an art I’d taken up

too late in life, presented me with a piece I should

learn to play, the second movement of Haydn’s

adagios always remind me of John, I’d read, at

a modest ceremony of remembrance for him,

from a text I’d prepared, which prophetically,

transcendentally, connected me with a

cornucopia of adagios, I’d sought them out,

been consoled, repaired, eventually inspired,

by them, Haydn’s Opus 76, no.1, movement

two, had been a total shoe-in

Haydn is where the history of string quartets

starts in the West, they existed before, but

not formally as a musical format, became

thereafter, however, an identifiable category,

and consequently, imitated

the string quartet, a piece of music written

for four instruments, all string traditionally,

two violins, a viola, and a cello, playing

more than one segment of music,

Classically three, then becoming four,

became a structure that has not even

nowadays lost its appeal, though the

individual combinations might’ve

significantly, since, been altered

Haydn wrote 68 string quartets, which

established him as their spiritual father,

all string quartets devolve from him,

including Beethoven‘s, those of

marvel

R ! chard

_____

if a trio is a sonata written for three instruments,

a sonata, a piece of music consisting of more

than one segment, or movement, written for

four instruments, is called a quartet

a quartet is also what we call the group itself

of four players

quartets can play more than just quartets, they

can also play waltzes, nocturnes, rhapsodies,

for instance, just as trios, groups of three, can

play more than just trios

but quartets, the form, have had a long and

glorious history, from Mozart and Haydn,

the Classicists, through Beethoven, an

ardent Romantic, to the more political

Shostakovich, enemy, for a time, of his

repressive Soviet state, and on to

Messiaen, who composed his own

concentration camp

let me start with the Messiaen, now that I’ve

whetted your appetite, and work our way back

to Mozart to see where we came from, and

how

there are seven movements in Quartet for

four, atonality abounds, discordant, not

unexpectedly, progressions, repetition also

takes its punches, not easily identifiable

throughout, but tempo, the third pillar of

Western music, more or less holds its

own, keeping the tradition, however

precariously, together, listen

it’s 1941, we’re in a concentration camp,

Messiaen is caught between hope and

despair, give the guy a break, he hasn’t

many absolutes to hold onto, tempo

might be one of them, the heartbeat,

pulse, perseverance, an actual human

pace, a rhythmic instinct, by which

eventually, hopefully, meaning

transpires

hope is in one’s creativity, he says, each

individual answer can be a tribute to

one’s own tribulations, our responses

can be poetry, lessons rather than

invectives, epiphanies rather than

agonies, may the Force, in other words,

be with you, in the face of even the most

trying difficulties, honour can supplant

trials, he concludes, given grace and

integrity

Beethoven says pretty much the same

corroboration

R ! chard

________

though there are other, and quite significant,

composers who fit into this category,

Beethoven, Schubert, and Chopin pretty

much define, all by themselves, the

Romantic Period

Chopin composed only two sonatas of note,

plus one more that is overlooked for being

an early, student effort, not up to the

standard of his later ones, Chopin, rather,

wrote mostly shorter pieces, nocturnes,

études, preludes, polonaises, and more,

that later became the very stuff of his

reputation

Schubert wrote enough sonatas that he

could be compared to Beethoven, indeed

it can be difficult to tell one from the other,

much as it can be difficult to tell Haydn

from Mozart, products in either case of

being both of their respective eras

when I was much younger, a guest among

a group of academics, where I’d been invited

by the host’s wife, a co-worker, what I knew

of Classical music, in the large sense, which

is to say comprising all of the musical periods,

Classicism, Romanticism, Impressionism,

and beyond, was all self-taught

is that Beethoven, I asked the host, about

a piece of music he’d put on

that’s Schubert, he replied, aghast, as

though I’d just farted

I blushed, deep red, confounded

Schubert, having great admiration for

Beethoven, took on many of the older

composer’s lessons, four movements

instead of the Classical three, for

instance, and many of the technical

tricks of his forebear

but there’s an essential component of

their styles that marks one from the

other, an easy way to tell them apart,

Beethoven always composes against

the beat, Schubert following it

listen to the first few notes of Beethoven’s

“Pathétique”, for instance, the beats are

erratic, confrontational, the mark of a

revolutionary, Beethoven was brashly

proclaiming his worth, he had something

to prove

Schubert, who was essentially playing

for friends, just wanted to entertain

them, which he did in spades, without

bombast or bluster

D959, for example, no swagger, no

ostentation, delivering nevertheless

something quite, and utterly,

enchanting, everything following,

unobtrusively, the beat

enjoy

R ! chard

_______

cause most composers, including the great

ones, didn’t write many sonatas, or not many

to equal their greatest compositions, I’ll skip

directly from Bach to Beethoven, who first

gave sonatas their commanding position

on the cultural map

he wrote 32, the early ones competent,

even admirable, others inspiring, several

completely transcendental

of the 32, here’s the first of my favourites,

“Pastorale”, German spelling, of 1801

you might wonder about all the letters and

numbers in the naming of early music, much

of it compiled by later musicologists, cause

titles hadn’t been given to musical pieces,

even Beethoven’s “Pastorale” had been

later provided by his publisher

music before the late Classical Period

might’ve been written down, but not

widely distributed, there wasn’t a

market for it until the advent of the

Middle Class, who now wanted

access to what the aristocracy had

earlier, what compositions existed

would’ve been the property not of

the composer, but of the duke,

baron, or prince who’d hired him

for his court, see Haydn here, for

when greater demand grew for music

manuscripts, titles little by little became

a manner of increasing marketing,

scores found their way throughout

Europe to supply the many amateurs

who’d gather and play before we had

television

some of these amateurs became

noteworthy performers, who also

began to proliferate, to fill the

burgeoning concert halls,

incidentally, there’s also a “Pastorale”

Opus 68, you might want to listen to

and compare

enjoy

R ! chard

“Mona Lisa“ ( c.1503 – c.1519)

__________

the next sonata, Beethoven’s “Piano Sonata

is one that everyone’s heard, if only ever in

fragments, right up there with “Jingle Bells”

in our musical repertory, in our cultural DNA,

or, for that matter, Beethoven’s, also, other

the initial chords are peremptory, have

resonated, echoed, reverberated,

throughout the ages

this is not, however, the way one should

be addressing the aristocracy, Beethoven

was speaking for the growing Middle

Classes, who, hungering for the status

and refinement of the elite, the French

Revolution having just happened, were

crowding the burgeoning concert and

recital halls cashing in on that interest

the artist was now the main attraction,

where earlier the performer had been

merely decorative, the sponsored

employee of an, however benevolent,

aristocrat, see Mozart, see Haydn

ages, his revolutionary stuff, thumbing

his nose at convention, demanding

attention

R ! chard

________

Haydn, profoundly underrated, was the

other pillar of Classical music during that

period, Beethoven, with half a foot only

in that era, uses its elements to yank us,

yelling and screaming, into the next, the

Romantic Era, 1800 to 1870 more or less,

more about which later

if Haydn sounds a lot like Mozart, it’s that

this piece was also written in 1789, both

were catering to the aristocracy, courts,

salons, music was therefore frivolous,

meant to be entertaining, not inspirational,

trills, a lot of decoration, technical agility,

prestidigitation over profundity

Beethoven will change all that, stay tuned

meanwhile, listen to, enjoy, Haydn’s Piano

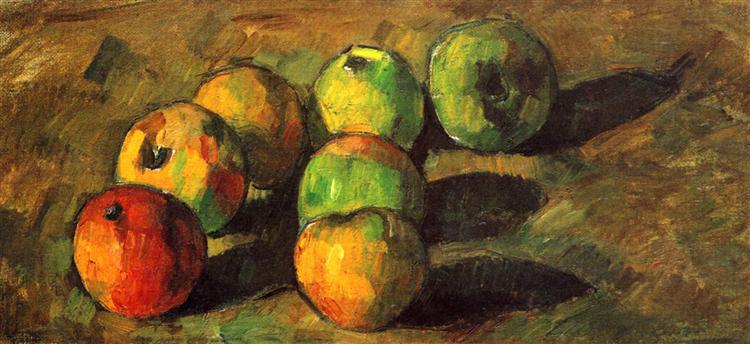

today’s prescribed apple

R ! chard

_____

is to an apple pie, its essential component,

after which the rest is decoration, however

inspired

sonatas existed before Mozart, but he’s

the one, along with Haydn, as well as

early Beethoven, who put them on the

musical map, 1750 to 1800, more or

less

it seems to me appropriate, therefore,

to start my Sonata Month then

here’s something by Mozart, 1789, his

three movements, fast, slow, fast – allegro,

adagio, allegretto – a perfect example of

the sonata as it was establishing itself

then, a piece of music consisting of

several distinct sections, movements,

meant to highlight contrasts, musical

agility in the artist, compositional

imagination

R ! chard

.jpg!Large.jpg)

Vincent van Gogh

_________

having introduced, however peripherally, in my

it wouldn’t be fair to not present Beethoven’s

contain iconic funeral marches, written, even

if you have no interest at all in such music, in

the blood of our Western culture, like

Shakespeare, to be or not to be, you’ve

heard the line, somewhere, even if you have

no idea what he might’ve been talking about

I don’t need to point out the dirges among

the movements, the solemn bits, they will

impose themselves, whether you’re paying

attention or not

Beethoven and Chopin sound a lot alike,

Beethoven, 1770 -1827, is earlier, pushed

the Classical Period into the Romantic Era,

pretty well, astonishingly, by himself

Chopin, 1810 – 1849, gives us the pinnacle

of Romantic music

I tell them apart by their beat, Chopin is

always on, Beethoven is always off, his

schtick, his revolutionary spirit, Chopin,

rather, played for the aristocracy, in

their courtly salons, much like Haydn,

but that’s another story

you might notice also that the last

all texture, a precursor to the later

Impressionism, in all of the arts

Beethoven, however, always takes

you on a journey, never gives you

merely background, there’s always

a core, a foundational melody

enjoy

R ! chard

_______

though I’ve focused especially, during

on Mozart, a second great pillar of

that era is Haydn, 1732 – 1809

here is one of his 62 piano sonatas,

which expresses more than anything

you’ve heard here yet the definition

of what music was at the time, or

should be, tonality, as I’ve earlier

said, tempo and repetition were

tantamount

listen for or the rigidity of the tempo,

the consistent melliflousness of

the melody, and therefore tonality,

and the repetition of all the

component tunes

I remember going to a drum recital

once, here in Vancouver, a guy was

expressing his artistry in a formal

venue, I was sitting in a forward

row, saw him set up his music on

his music stand, and I thought,

he’s going to have to turn the

pages, which he did, a drummer

that’s all I remember of the

presentation, but that was enough,

an entire revelation

turns the pages of his score, back

and forth, an interesting visual

expression of the imperative of

repetition in that era’s music,

having to return to what had

been written on the previous

page

also note that trills abound

note too in the second movement,

the adagio cantabile, the sudden

introduction of arpeggios,

transcendent, as though angels

had just appeared

which prefigures the metaphysical

aspirations of the Romantic Period

which ensued, see, for instance,

note also that we’re on fortepiano

here, a period instrument, a cross

between the harpsichord and the

modern instrument

R ! chard

.jpg!Large.jpg)