Richibi’s Weblog

Just another WordPress.com weblog

Category: up my idiosyncrasies

August 15, 2023

how to listen to music if you don’t know your Beethoven from your Bach, XVIII – Rachmaninov

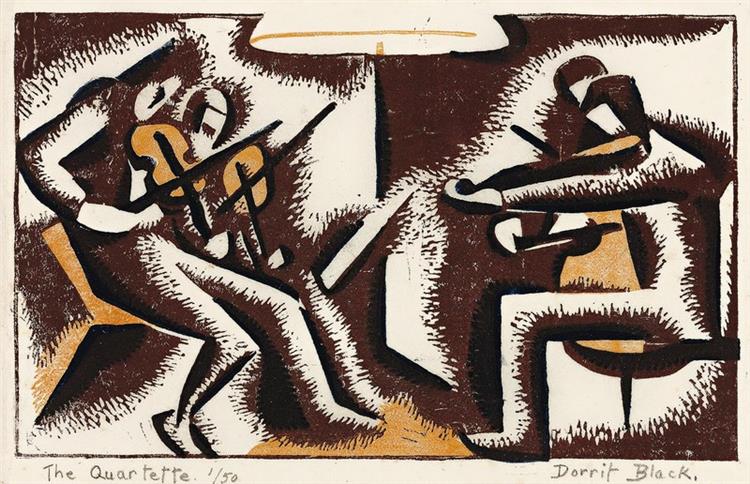

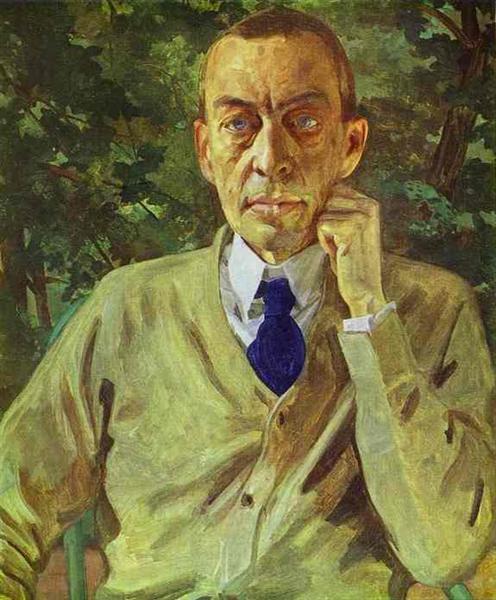

“Portrait of the composer Sergei Rachmaninov“

Konstantin Somov

______

though you probably still wouldn’t be able

to tell a prelude from a hole in the wall,

nor, admittedly, can I, unless indicated,

if you’ve listened to the pieces I’ve

recently presented, you’ve noted, even

merely sensed, really, that the preludes

of one composer don’t sound at all like

those of the others, Bach doesn’t sound

like Chopin, who doesn’t sound at all

like Debussy, the first step in telling

your Beethoven from your Bach, as

promised in my title

you might not even be able to tell which

is which as you’re listening, but you can

tell they’re different, you do the same

thing telling your Monet from your

Renoir

Rachmaninov also wrote, like Chopin,

and Debussy, 24 preludes, and, like

Chopin, in every key, major and minor

but spread out through three publications,

Opus 3, no. 2, from 1892, comprising of

only one prelude, but a scorcher, The

a second set, Opus 23, consists of ten,

mostly iconic, pieces, you’ve heard

them somewhere before, therefore

iconic

the final set comes out in 1910,

Opus 32, with thirteen preludes,

for a total of 24

you’ll marvel, even Marilyn Monroe

famously did

enjoy

R ! chard

April 26, 2023

how to listen to music if you don’t know your Beethoven from your Bach, XII – on rhapsodies

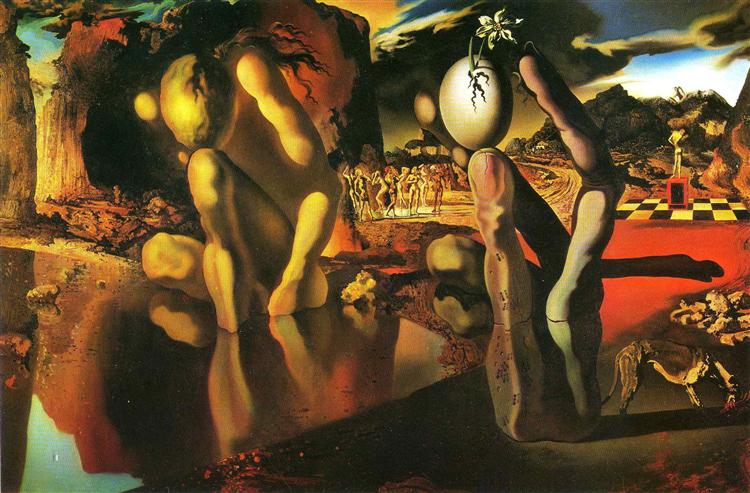

“Rhapsody“ (1958)

_____

if, in my last instalment, I compared iconic

funeral marches, let me do the same for

a couple of iconic rhapsodies, another

musical form that came and went, that’s

come and gone, but not forgotten

what’s a rhapsody

as far as I can make out, it’s much the

same as a fantasia, if you can remember

what a fantasia is, a free form composition,

but with a Romantic, which is to say a

heartfelt, twist, more pathos, less

technical wizardry

Gershwin wrote his Rhapsody in Blue

in 1924, you can hear New York, Times

Square, Broadway, from the first wail

of the languid horn

Rachmaninov’s Rhapsody on a Theme

of Paganini, written in 1934, ten years

later, gives you, however, Vienna, its

Romantic Period, the traditions of,

a century earlier, Beethoven, Schubert

Rachmaninov is personal, introspective,

tragic, Gershwin is extroverted, social,

fun

Rachmaninov looked back to his

European, Old World, traditions,

Gershwin augurs an entirely new

voice

listen, you can hear it

enjoy

R ! chard

January 13, 2023

how to listen to music if you don’t know your Beethoven from your Bach

“Music“(1895)

Gustav Klimt

________

how to listen to music if you don’t know your

Beethoven from your Bach

the first thing to do, I would suggest, is to stop

and listen, spend the time with the work you’re

listening to, it’s no different than spending half

an hour with a friend

but you have to be there, listen, as you would

with a friend, no cell phones

the next thing I suggest is to compare, put your

work up against a different composer, a

different interpretation, a different version of

the piece you have on hand

I learned this as I learned to tell one artwork

from another, while I turned European art

museums into personal art history classes,

spending hours comparing one painting

with another, doing so chronologically,

century after century, imbibing thereby the

history of Western art

it’s not necessary to know who you might

even be listening to, just listen, hear,

later the names will come

here’s some Mozart, here’s some Prokofiev,

for instance, you’ll tell the difference

instinctively, forget about the composers,

just surrender to the magic

here’s a poem which says more or less

the same thing

How to Read a Poem: Beginner’s Manual

First, forget everything you have learned,

that poetry is difficult,

that it cannot be appreciated by the likes of you,

with your high school equivalency diploma,

your steel-tipped boots,

or your white-collar misunderstandings.

Do not assume meanings hidden from you:

the best poems mean what they say and say it.

To read poetry requires only courage

enough to leap from the edge

and trust.

Treat a poem like dirt,

humus rich and heavy from the garden.

Later it will become the fat tomatoes

and golden squash piled high upon your kitchen table.

Poetry demands surrender,

language saying what is true,

doing holy things to the ordinary.

Read just one poem a day.

Someday a book of poems may open in your hands

like a daffodil offering its cup

to the sun.

When you can name five poets

without including Bob Dylan,

when you exceed your quota

and don’t even notice,

close this manual.

Congratulations.

You can now read poetry.

Pamela Spiro Wagner

music is also like that

R ! chard