Richibi’s Weblog

Just another WordPress.com weblog

Category: Mozart

April 27, 2024

a veritable Schubertiade, VII

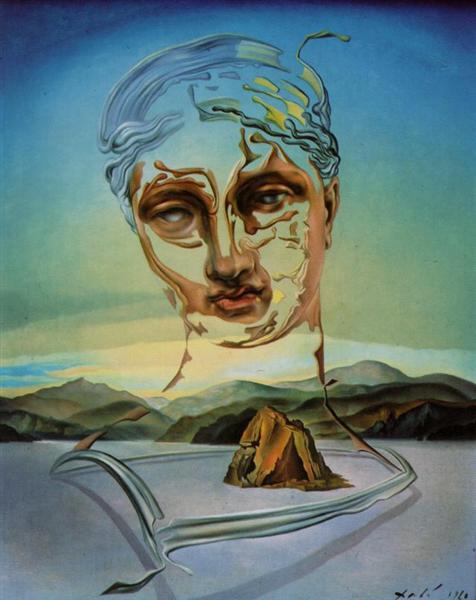

“Birth of a Divinity“ (1960)

Salvador Dali

______

during the third evening of recitals, the

program, to my surprise, starts with a

work even earlier than the earliest

one we’ve heard yet in this

Schubertiade, his D 568, his Seventh

Schubert’s Piano Sonata No. 4 in

A minor, D 537, was written when

he was seventeen, he would’ve

been, and was, steeped in Mozart,

music to amuse musical coteries

but at the start of the second movement,

I heard an air I’d heard somewhere

before, it turned out to be the seed of

a magical part in one of his later

transcendental pieces

Schubert was already imbued with his

divinity, see above, you can hear it,

listen

R ! chard

April 23, 2024

a veritable Schubertiade, VI

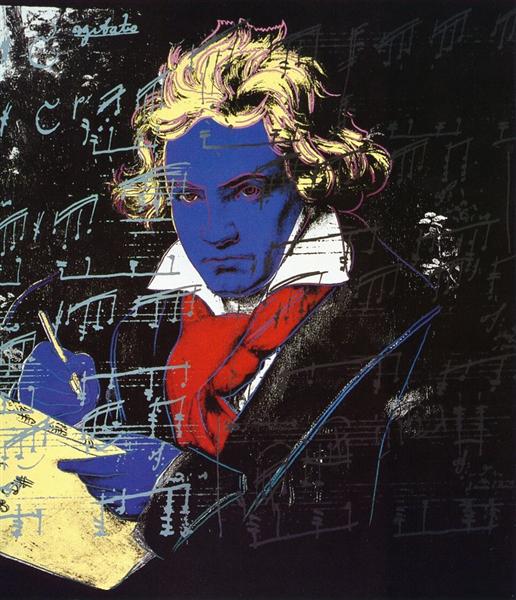

by this time, in his Piano Sonata in A minor,

D 845, Schubert has accumulated so much

Beethoven that his Beethoven is beginning

to shine through in his own compositions,

Beethoven was a forefather, still present,

it’s often difficult to tell one, indeed, from

the other, even here

Beethoven, see above, punched through

Classicism – Mozart, Haydn – its artificiality,

delivering emotion, instinctively, from the

very start, from which he nearly

single-handedly delivered to the world no

less than Romanticism, like delivering the

recalibration of time and space after

Einstein essentially, so profound a

cultural metaphysical reorganization

Schubert remains ever more courteous,

more beholden to the upper crust that

supports him, and that he ever wants to

court, you can hear it, listen, there is no

confrontation here, just, dare I say,

entertainment

Schubert was not a revolutionary

R ! chard

April 18, 2024

a veritable Schubertiade, V

“The Dreamer“ (1820 – 1840)

Caspar David Friedrich

______________

from the start, in his Piano Sonata in C major, D 840,

Schubert is steeped in Mozart, the exhilaration, the

fantasy, not surprisingly, Mozart is Schubert’s

motherland, the courts, the salons, the chamber

music, in Schubert’s day, aristocrats still sponsored,

to a great degree, the arts

but soon the Romantic impulse takes hold, the

introduction of melancholy into the mix, rather

than sang froid, artifice, merely, Schubert has

imbibed, to supplement his manifest technical

agilities, the temper of the times, Schubert is

moving his cultural world forward, into

Romanticism, see above

there are only two movements in his D 840,

there are sketches of its third and fourth

movements, but Schubert had abandoned

them, the sonata, unfinished, was only

published after he died, profoundly worthy

still, if truncated

what do you think

April 16, 2024

a veritable Schubertiade, IV

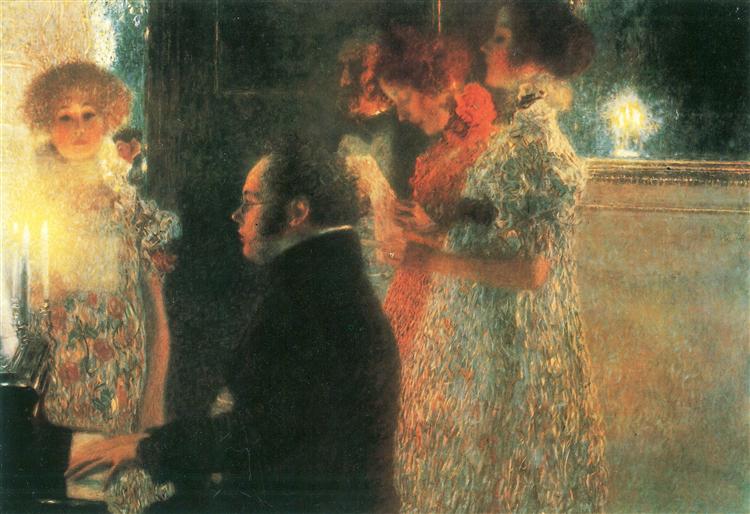

“Schubert at the Piano II“ (1899)

Gustav Klimt

______

for the second evening of Schubert sonatas

during my May Schubertiade, it wouldn’t be

surprising to hear again an early work, 1819,

Schubert would’ve been 22, the series is

undoubtedly and necessarily somewhat

chronological

his Piano Sonata in A major, D 664, is

blatantly anchored in the Classical idiom,

you can hear Mozart all over the place, not

all pejoratively, Mozart is effervescent, full

of exuberance and creativity, Schubert

diligently follows

but Romanticism equals intimacy, poignancy,

which Schubert touches upon in his andante,

the second movement, to a degree not yet

as markedly as, for instance, Chopin yet,

famous for his sweeping Romanticism, but

still convincing and promising

the third movement, the allegro, is right back

at Mozart, to delight the aristocracy, his

essential audience, see above

listen

R ! chard

April 9, 2024

a veritable Schubertiade, III

“Impression, Sunrise“ (1872)

Claude Monet

________

what struck me most about Schubert’s Piano

Sonata no. 17 in D major, his D850, was, more

than its emotional impact, its technical

wizardry, from the start Schubert dazzles with

his prestidigitation, his manual dexterity, the

notes fly

there’s a lot of Beethoven in this composition,

working against the beat, apart from the fourth

movement, the rondo, Schubert is being

unequivocally Beethoven

the fourth movement is, incidentally, utter

Mozart, you can tell from the preponderance

of trills

texture, meanwhile, overcoming melody,

in, most notably, the third movement, is

right out of Chopin, his “Winter Winds“

for instance, an inspired combination

of both melody and texture, where is

the supremacy of either, listen, you tell

me, do the “Winds“ conquer the groans,

the tribulations, of the underlying melody,

the left hand, the low notes, the chthonic,

the earth, or does the dexterousness of

the right hand, the ephemeral, the

transitory, win the day

texture will overcome melody eventually,

as the century moves along, Impressionism

will prioritize perspective over emotion, the

head over the heart, Debussy, among

others, Renoir, Monet, Pissaro, will

dominate, see above, but that’s another

story

meanwhile Schubert

listen

R ! chard

April 5, 2024

a veritable Schubertiade

“Una melodia de Schubert” (c.1896)

___________

in May, the recital society of my city is featuring

an internationally famous pianist doing several

Schubert sonatas, twelve of them, spread out

across four evenings, a veritable Schubertiade,

I’ve got tickets for all of them

maybe you’d like to join me

I always do my research before attending any

cultural event, much like reading up on Italy,

for instance, before going there

the program seems to be more or less

chronological, the first night featuring

earlier Schubert sonatas

his D568, his Seventh, composed in 1817,

is, to my mind, enchanting, but not yet

reaching the heights of his later

transcendental productions, more of

which later, should you stick around

Schubert always sounds a lot like Beethoven,

but with more civility, less confrontation,

Schubert is still chamber music, and, in this

outing, I find he sounds a lot like Mozart even,

dexterous, delightful, but fundamentally

frivolous

it’s the difference between dessert and food

that will sustain you, that’ll speak to your soul,

more about which later, should you stick

around

meanwhile, D568, enjoy

R ! chard

December 24, 2023

sonatas, continued (Messiaen – “Quartet for the End of Time”)

“Red Quartet“

Raoul Dufy

_____

if a trio is a sonata written for three instruments,

a sonata, a piece of music consisting of more

than one segment, or movement, written for

four instruments, is called a quartet

a quartet is also what we call the group itself

of four players

quartets can play more than just quartets, they

can also play waltzes, nocturnes, rhapsodies,

for instance, just as trios, groups of three, can

play more than just trios

but quartets, the form, have had a long and

glorious history, from Mozart and Haydn,

the Classicists, through Beethoven, an

ardent Romantic, to the more political

Shostakovich, enemy, for a time, of his

repressive Soviet state, and on to

Messiaen, who composed his own

Quartet for the End of Time, in a Nazi

concentration camp

let me start with the Messiaen, now that I’ve

whetted your appetite, and work our way back

to Mozart to see where we came from, and

how

there are seven movements in Quartet for

the End of Time, not the Classical three or

four, atonality abounds, discordant, not

unexpectedly, progressions, repetition also

takes its punches, not easily identifiable

throughout, but tempo, the third pillar of

Western music, more or less holds its

own, keeping the tradition, however

precariously, together, listen

it’s 1941, we’re in a concentration camp,

Messiaen is caught between hope and

despair, give the guy a break, he hasn’t

many absolutes to hold onto, tempo

might be one of them, the heartbeat,

pulse, perseverance, an actual human

pace, a rhythmic instinct, by which

eventually, hopefully, meaning

transpires

hope is in one’s creativity, he says, each

individual answer can be a tribute to

one’s own tribulations, our responses

can be poetry, lessons rather than

invectives, epiphanies rather than

agonies, may the Force, in other words,

be with you, in the face of even the most

trying difficulties, honour can supplant

trials, he concludes, given grace and

integrity

Beethoven says pretty much the same

thing in his last piano sonata, remember,

his Opus 111, listen, a not not impressive

corroboration

R ! chard

November 22, 2023

November / Month of the Sonata – 22

“Piano“

José Garnelo

_____

having heard Stravinsky’s Concerto for

Two Pianos already, if you’ve taken in

my last instalment, you’ll find it perhaps

the most instructive of any of my

suggested comparisons to hear beside

it Mozart’s Sonata for Two Pianos, the

first, written in 1935, the second, 1781,

you’ll hear the passage of time fly by

both here are played by the same two

performers, brothers, incidentally, an

extraordinary couple, making your

aesthetic decision that much more

contained, straightforward

though Stravinsky might be here

utterly unexpected, even disarming,

he’s evidently much more in tune

with the Twentieth Century, even

the 21st, than the more bucolic

music of, energetic as it is, Mozart,

who is not of our era, however still

entirely relevant

with Stravinsky, you hear the traffic,

the hustle and bustle of modern life,

the pulse and frenzy of a more

frenetic century, though it must be

remembered that Mozart wrote his

piece between the American, 1776,

and the French, 1789, Revolutions,

a couple of historically seismic

events, not at all not turbulent

if you listen, you can hear it all in

the music, art is like that

enjoy

R ! chard

November 18, 2023

November / Month of the Sonata – 18