November / Month of the Sonata – 15

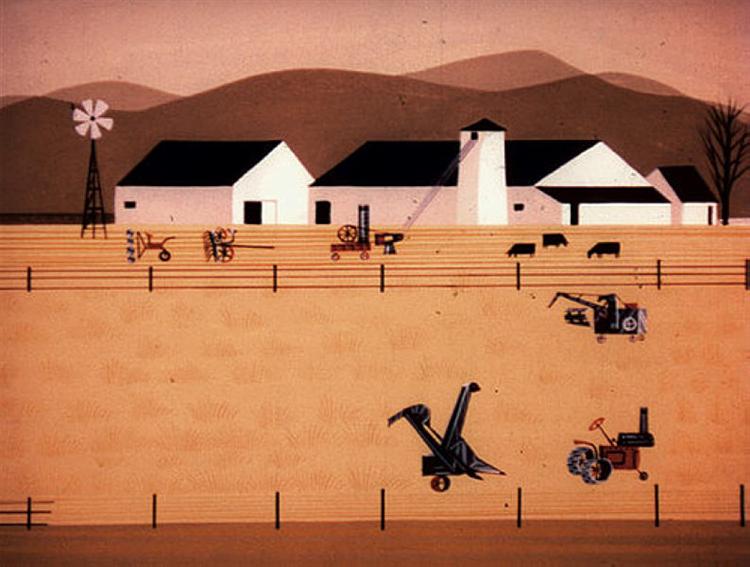

“Rhapsody of Steel“ (1959)

________

so what’s a rhapsody

_

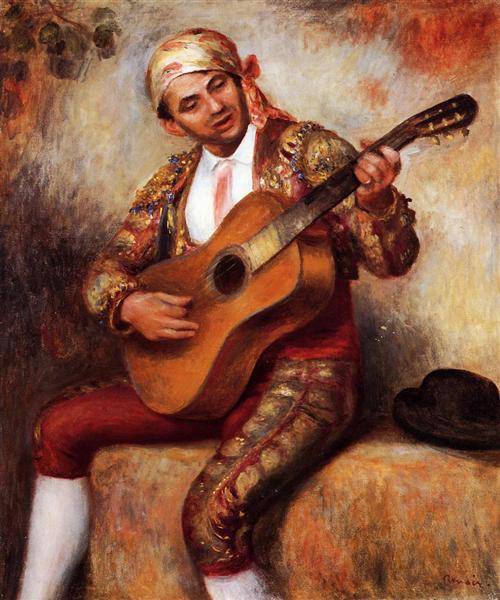

“Liberty Leading the People“ (1830)

_________

for everyone, with great gratitude,

who reads me, I mean only to

bring poetry, which is to say,

light

though I’d considered leaving the

Romantic Piano Concertos behind

to explore other areas of the period

in this survey, it seemed unfair,

indeed remiss of me, not to include

the three among my top ten that I

haven’t yet highlighted, Beethoven’s

2nd, 3rd, and 4th Piano Concertos,

Opuses 19, 37, and 58 respectively,

after all, these are where the spirit

of the age, the Zeitgeist, was

constructed, like a building, with

walls, windows, a hearth, all of

which would become a church,

then a Church, and by the time of

Brahms, a very Romantic Cathedral

the foundation had already been laid

by Mozart with his 27, but music had

not yet become anything other than

an entertainment by then, or

alternatively, an accessory to

ceremonial pomp and circumstance,

see Handel and England for this, or

liturgical stuff, see, among many

others here, Bach

but with the turn towards

independence of thought as the

Enlightenment progressed, cultural

power devolved from the prelates,

and their reverent representations,

to the nobles, who wanted their own

art, music, which is to say, something

secular, therefore the Classical

Period, 1750 – 1800, in round figures

then in the middle of all that, 1789,

the French Revolution happened,

and the field was ripe for prophets,

anyone with a message of hope,

and a metaphysical direction, midst

all the existential disarray – the Age

of Reason had set the way,

theoretically, for the possibility of a

world without God, something, or

Something, was needed to replace

the The Trinity, the Father, the Son,

and the Holy Ghost, Who had been

seeing Their supremacy contested

since already the Reformation

Beethoven turned out to be just

our man, don’t take my, but history‘s

authentification of it, see the very

Romantic Period for corroboration

in a word, Beethoven established a

Faith, a Vision, not to mention the

appropriate tools to instal this new

perspective, a sound, however

inherited, musical structure – his

Piano Concertos Two, Three, and

Four, for instance, are paramount

amongst a host of others of his

transcendental revelations

briefly, the initial voice, I am here, in

the first movement, is declamatory,

even imperious, but ever

compositionally solid, and proven,

tempo, tonality, recapitulation, the

materials haven’t changed from the

earlier Classical epoch, just the

design, the interior, the

metaphysical conception

his construction is masterfully

direct, the line of music is

throughout ever clear and concise,

despite flights of, often, ethereal,

even magical, speculation, you

don’t feel the music in your body

as you would in a dance, as in the

earlier era, of minuets, but follow

it, rather, with your intellect, you,

nearly irresistibly, read it

but the adagio, the slow movement,

the middle one Classically, is always,

for me, the clincher, the movement

that delivers the incontrovertible

humanity that gave power to the

Romantic poet, who touched you

where you live

Beethoven says life is difficult, and

eventually, at the end of his Early,

Middle and Late Periods, life may

even have no meaning

but should there be someone, he

says, who is listening, Someone –

though implicit is that one may be

speaking to merely the wind – this

is what I can do, this is who I am

and while I am here, however

briefly, I am not insignificant, I

can be worthy, even glorious,

even beautiful, I am no less

consequential, thus, nor

precious, than a flower

for better, of course, or for worse

R ! chard

“Egg on Plate with Knife, Fork, and Spoon“ (1964)

____

after my somewhat prolonged side trip

into Bach country, though it is a land

of many more wonders, I’ll get back

on track, more or less, here, with

Beethoven’s Second Cello Sonata,

the other half of his Opus 5

till then, the cello had served as

accompaniment, essentially, for other

more discursive, higher pitched, less

sonorous, less stentorious

instruments

but Beethoven puts the cello back

into the hottest seat in the house, right

next to the ubiquitous piano, a

requirement in any instance following

the neglect of the cello during the

intervening Classical Period, despite

Bach’s earlier luminous illustration of

its incandescent potential

the Opus 5, no 2 starts, audaciously,

with an adagio, not always a wise

choice, as you’ve heard me repeat

here before, it can be unentertaining

but Beethoven gives his adagio tension

by introducing breaks often, which,

rather than stultify, creates momentum,

therefore a narrative, a story to follow

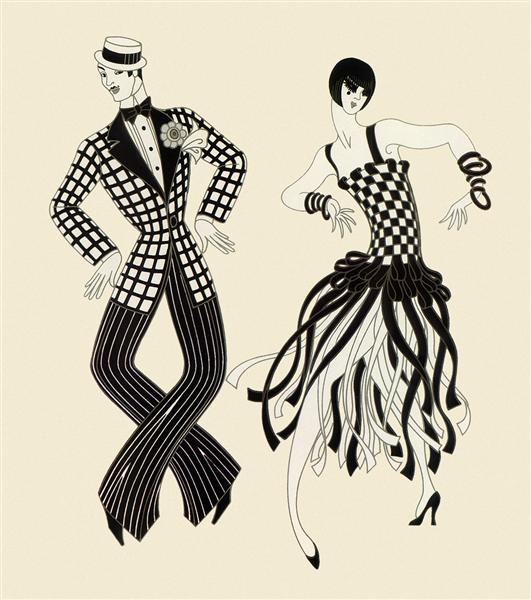

the rhythm is no longer adjusted to

dance essentially, such a spin as is

heard in the second and third

movements, for instance, would

surely sweep one off one’s feet

but the art is in the dance that

Beethoven allows and creates between

the piano and the cello, the first the

filigree on the arm of the more grounded,

more entrenched latter, the crystal, the

silverware that adorn, symbolically, an

however majestic oak table, the creamy

Hollandaise that makes an egg, however

elemental, irresistible, the literary turns

that might transform mere prose into,

verily, poetry, icing on a cake, in a word,

to complement, in stunning and equal

cooperation, the inextricable

counterpart

there is even a moral lesson transmitted

here

Beethoven can often be long-winded,

I’ve found, but there’s always, always,

at the end of the road something

entirely worth the extra minute, the

even several extra minutes

R ! chard

“Joseph Haydn“ (ca. 1791)

_____________

for, especially, Collin

Haydn’s Opus 42 was written in 1785,

he would’ve been 53, which might

explain his return to a less

ideologically driven music than his

earlier more vociferous compositions,

one gets more conservative, nearly by

definition, as one gets older

there is no vehemence in this quartet,

it is meant to merely delight listeners,

lords and ladies looking to be

impressed, there is no call to arms

here, there’s even a minuet

the final movement, the presto, might

seem urgent, but is rather, I think,

engaging than peremptory, more

entertaining than adamant

there’s only one string quartet in the

Opus 42, usually there are six in

Haydn’s opuses, or opera, the piece

is also terse, a wonderland of

extraordinary music within the span

of, however improbably, just 13

minutes

Haydn seems to be giving us his idea

of the string quartet, a nearly Platonic

proposition, in a nutshell

Plato thought that there was an ideal

string quartet somewhere up there in

an ordering space, a mystical

system of specifically representative

entities, determining the accuracy of

definitions, religions presently

struggle with that, the inflexibility of

their intractable propositions, Haydn

was giving us something to think

about, a string quartet to define the

very ages

note the recurrence of the original

theme always with all of its

permutations

note the rhythmic consistency,

though the several movements are

decidedly, and effectively, divided

according to their strict tempos

note that all, though here and there

a strident note may appear, the

tonality, the key, the modality, is

constant

this will change

but for now we have the very essence

of the Classical Period

and it’s hot

R ! chard

psst: to a friend who’s become impressed

by my choice, incidental of course,

of cellists, I would suggest it has

more to do, perhaps, with its sonority,

the low thrum of their instrument, it

can really unsettle one’s kundalini,

the sleeping serpent at the base of

the spine, and not so much the

individual cellist, maybe