Symphony no 11 in G minor, opus 103 (The Year 1905) – Dmitri Shostakovich

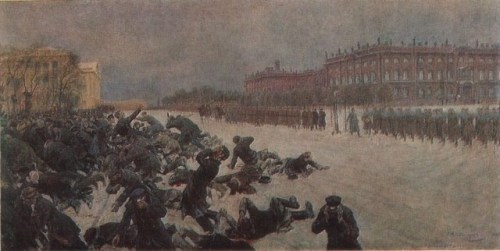

“Bloody Sunday. Shooting workers near the Winter Palace January 9, 1905”

“Bloody Sunday. Shooting workers near the Winter Palace January 9, 1905”

________

if you don’t find a lot to hang on to in

Shostakovich’s 11th Symphony, as I

didn’t, apart from his everywhere

ravishing instrumentation, it’s that

the piece is a commemoration of a

particular event in Russian history,

Bloody Sunday, when the Tsar’s

Imperial Guard opened fire on a

crowd of unarmed protestors who

had come to petition Nicolas ll for

better work conditions, akin, indeed,

to slavery then, there, January 22,

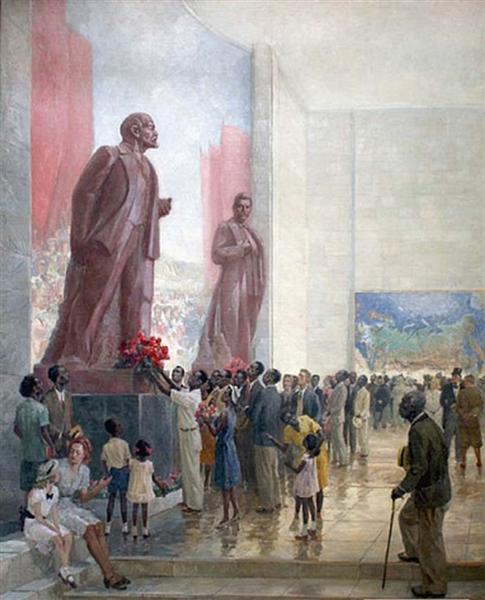

1905, the first stirrings, thus, of the

1917 Russian Revolution, which

installed the Bolsheviks, Leninism,

then Stalinism, and so forth

Bloody Sunday can be compared to

China’s Tiananmen Square, June 4,

1989, it seems totalitarian states will

blithely resort to such dire measures

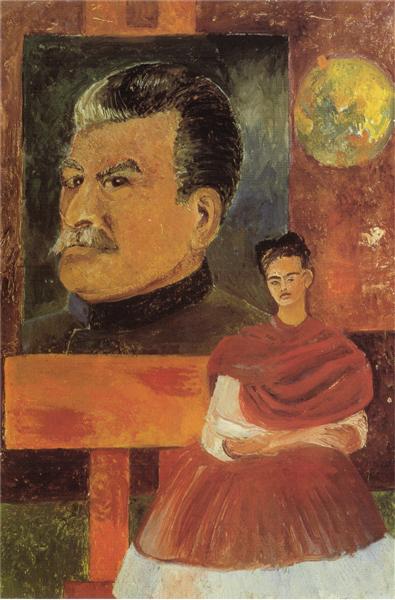

Shostakovich had been commissioned

to write a symphony for the 50th

anniversary of the event, January 22,

1955

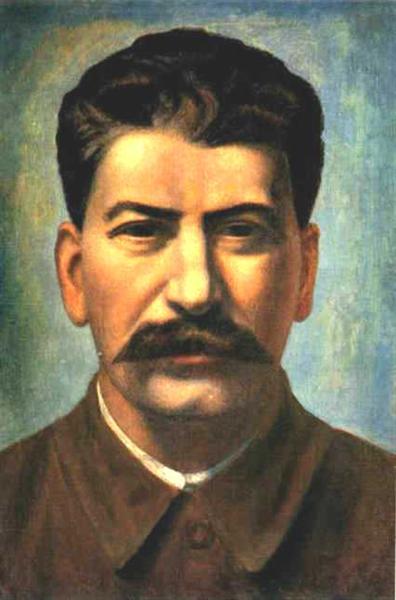

he’d been reinstated by Khrushchev

after the death of Stalin, who’d

excused the tyrant’s condemnation

of Shostakovich by saying the despot

had been too subjective, and rescinded

the law which that earlier ruler had

imposed requiring all artists to

conform to party ideology, see Hitler

again on that one, his proscribed

entartete Kunst, his interdicted

degenerate art

but for personal reasons, Shostakovich

was unable to compose this new work

until 1957, the year after the Soviets had

quashed the Hungarian uprising of 1956

with tanks and ammunition, an event

too reminiscent of, to the composer, the

earlier tsarist massacre, and horrifying

furthermore, his father had been there,

and spoke of children having been shot

out of the trees as they merely watched

the proceedings, felled too suddenly,

apparently, to wipe the smiles off their

innocent still faces

the Symphony is called “The Year 1905“,

it is mighty, but is too local to effect any

universal understanding, I think, the

program is too specifically Russian to

evoke more than historical attention to

an unacquainted observer, listener

I’d visited a church in Rome, Sant’Agnese

fuori le mura, St Agnes Outside the Walls,

once, a place I would not miss were I ever

to return to that illustrious city, before even

the Vatican, the Coliseum, et cetera, the

church was built in the 4th Century and

has weathered the ages, the vicissitudes

of time, with all their impositions

the mass was in Italian, however, not the

Latin that had once united all Catholics

in a common set of sounds that had been

internalized to represent the message of

the service

but now I could only recognize the form,

no longer the content, something like the

response a person without the history

of Russia would have here, I would

contend

this is the dilemma of this, however

significant, composition, I find

you might also imagine that a tribute to

Canadian soldiers who’d died at, say,

Vimy Ridge, or Passchendaele, might

not be as moving to someone who

wasn’t Canadian

Shostakovich received the Lenin Prize

for his achievement, one of the Soviet

Union’s most prestigious accolades

R ! chard