String Quintets – Mozart / Beethoven

“Egg on Plate with Knife, Fork, and Spoon“ (1964)

____

after my somewhat prolonged side trip

into Bach country, though it is a land

of many more wonders, I’ll get back

on track, more or less, here, with

Beethoven’s Second Cello Sonata,

the other half of his Opus 5

till then, the cello had served as

accompaniment, essentially, for other

more discursive, higher pitched, less

sonorous, less stentorious

instruments

but Beethoven puts the cello back

into the hottest seat in the house, right

next to the ubiquitous piano, a

requirement in any instance following

the neglect of the cello during the

intervening Classical Period, despite

Bach’s earlier luminous illustration of

its incandescent potential

the Opus 5, no 2 starts, audaciously,

with an adagio, not always a wise

choice, as you’ve heard me repeat

here before, it can be unentertaining

but Beethoven gives his adagio tension

by introducing breaks often, which,

rather than stultify, creates momentum,

therefore a narrative, a story to follow

the rhythm is no longer adjusted to

dance essentially, such a spin as is

heard in the second and third

movements, for instance, would

surely sweep one off one’s feet

but the art is in the dance that

Beethoven allows and creates between

the piano and the cello, the first the

filigree on the arm of the more grounded,

more entrenched latter, the crystal, the

silverware that adorn, symbolically, an

however majestic oak table, the creamy

Hollandaise that makes an egg, however

elemental, irresistible, the literary turns

that might transform mere prose into,

verily, poetry, icing on a cake, in a word,

to complement, in stunning and equal

cooperation, the inextricable

counterpart

there is even a moral lesson transmitted

here

Beethoven can often be long-winded,

I’ve found, but there’s always, always,

at the end of the road something

entirely worth the extra minute, the

even several extra minutes

R ! chard

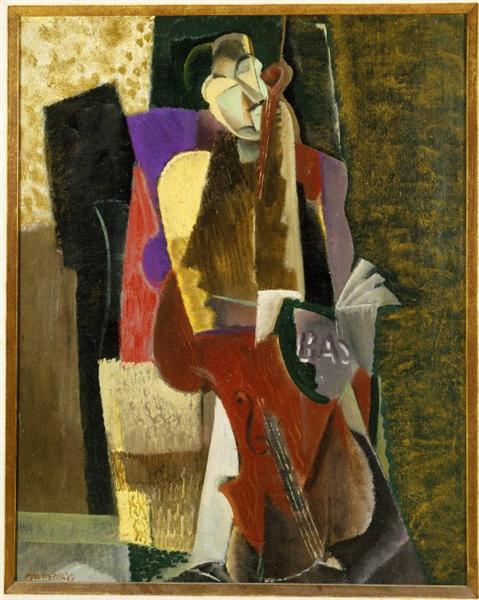

“A Cello“ (1921)

___________

between Bach’s transcendent Suites for

Cello and Beethoven’s reinvention of that

instrument, two only cello works occupy

the last half of that century, both by

Haydn

his Second, however, Concerto, written

several years later than his First, 1783,

indeed nearly twenty years later, seems

to me less accomplished, though ever,

nevertheless, unimpeachably, and

impressively, Haydn

the first movement is long, long works

only until you start thinking it’s long

the initial melody in the adagio, the

second movement, struck me as artificial,

saccharine, though Haydn weaves magic,

not unexpectedly, still, and

continuously, around it in its

development, his elaboration of it

and the pace of the third movement,

following the second, is disconcerting

rather than surprising, rather than,

were it effective, delightful

Mozart wrote a Cello Concerto too,

apparently, but, if so, it is lost

otherwise we’re on to the next historical

epoch, Beethoven’s, after this inauspicious

turn at this generation for the cello, lost

for a while among the more assertive

instruments of that prim, and proper,

Classical Era

R ! chard

“St. George and the Dragon“ (c.1470)

________

it isn’t easy for me to leave Bach behind

whenever I start listening to him, I could

ride his musical train forever

but the middle of the 18th Century did, put

him aside, for about a hundred years, until

Mendelssohn rediscovered him

Bach’s Cello Suites were themselves only

reinstated in the 1930s by Pablo Casals,

the Classical 18th Century had considered

Bach too fussy, his pieces, they thought,

were technical exercises rather than

actual entertainments, form was

overtaking, for them, function

there’s a wonderful book about all this,

“The Cello Suites“, written by Eric Siblin,

a Canadian journalist, which is not only

amazingly informed and probing, but also

beautifully written, it holds a place of

honour on my bookshelf, along with other

inspired, and inspiring, texts

not only was Bach set asunder, dismissed,

during the Classical Era, but all of the

formative music also he had written, for

cello, violin, keyboard, in other words,

the entire curriculum

which, since Bach’s reinstatement, has

become, paradoxically, the very

foundation for learning these instruments

imagine playing a tune with the right

hand, then a few notes later, picking

it up in the left hand while the right

hand keeps on going, imagine what

that does to your fingers, never mind

to your mind, that’s what his Two-Part

Inventions are all about, fifteen of

them, eight in major keys, seven in

minor, consider the technical

difficulties, intricacies, imposed

both compositionally and upon

the harried performer

then Bach follows through with his

Three-Part Inventions to top it all

off, for the keyboard at least, and

only for the moment – there’ll still

be his transcendental “Goldberg

Variations” among other

incandescent masterpieces –

wherein one juggles three tunes at

a time, and all of them in the same

assortment of fifteen contrasting,

foundational, keys, the “Inventions“

– if you can do that, you’re on your

way, one would think, to knowing

entirely what you’re doing

but time marches on, the Classical

Era hits, Haydn takes over, not

unimpressively

the same thing happened in my

generation to Frank Sinatra via

the Beatles, not to mention, a little

later, to either, with Pink Floyd

listen to Haydn’s First Cello Concerto,

note the bravura inherent in the

composition, this is not Bach’s

meditative music, the very Romantic

Period is, through Classical reserve,

expressing already its imminence,

individual prowess is taking over

from community, which is to say

religious, affiliation, the same way

the Renaissance artists, Duccio,

Giotto, Fra Angelico, Filippo Lippi,

Uccello had stood out, incidentally,

from their brethren in the standard

communal art schools dedicated to

decorating the ever burgeoning

churches sprouting out in the still

fervent European environment

musical, though unaristocratic,

talents, this time, were beginning,

within a German context, to flex

their decidedly not unimpressive

muscles, and gaining some

significant purchase

and who wouldn’t when a Cello

Concerto would’ve sounded like

this, listen

R ! chard

“The Cellist“ (c.1917)

______

what struck me immediately upon hearing

the bow’s very first strokes on the violin in

this Fifth Cello Suite of Bach was that the

mood was not only brashly Romantic, but

quite specifically Russian Romantic, right

up there with Dostoyevsky, and “Fiddler

on the Roof“, dark brooding colours at

first, followed by long plaintive musical

phrases, you can even hear the sound of

the steppes, I thought, stretching out into

the endless distance, this performance,

I surmised, is not, other than

compositionally, Baroque, not to mention

not even German

yet as played by Mischa Maisky, it’s one

of the best versions of the Fifth I’ve ever

heard, and if it works, who’s to complain

but more context – Bach never gave not

only textural indications, but not even

tempos to his pieces, apart from the

very dance terms that identify the

movements, so what, therefore, is the

specific pace, you’ll ask, of a courante,

for instance, you tell me, I’ll reply

in other words, the modular terms were

significantly looser in the early 18th

Century than later, when metronome

markings would begin to demand more

accurate replication of the artist’s

explicit specifications – Beethoven

especially made sure of that, by

requiring accurate renderings of his

mood or pace indications, largo,

allegro, andante, for instance, still less

strict than the stipulation later for exact

musical beats per minute – trying to

keep pace with a prerecorded tape, for

example, as in again the industrially

driven, which is to say emotionally

indifferent, context of the seismic

“Different Trains“, a masterpiece of a

more technically conditioned era

I don’t think that Bach would at all have

been disappointed that the heirs of his

fervent, though more genteel, creations

might’ve morphed into something

profound for other groups, be they

national, or of a class, or of even a

generation, of people, which is to say

that these works have superseded

their merely regional intent, and have

reached beyond space and time, the

very purview of music, to speak a

common and cooperative, indeed a

binding, language

I said to my mom the other day that if

we all sang together, we could save

the world

R ! chard

psst: Maisky’s encore,, incidentally, is from

the “Bourrée” of Bach’s Third Cello

Suite, note this contrasting, more

courtly – more refinement, more

reserve – rendition, you can even

hear, not to mention see, in this

particular instance, not Russian

steppes, but European trees on

their baronial estates, if you lend

an attentive ear

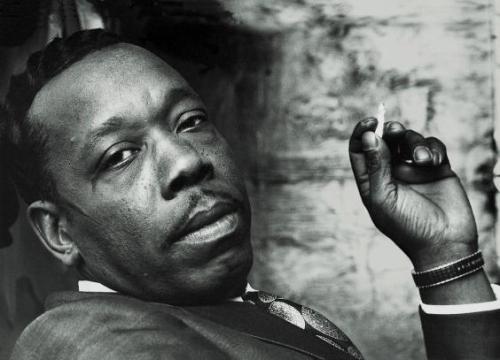

Slim Harpo (1924 – 1970)

______

for Barbara

having read my musings on the guitar‘s

superior practicality, easy portability,

as a carry-along instrument on the range,

a friend replied, “how about a cowboy

with a harmonica“, and mentioned Slim

Harpo, I told her I’d look into it, how

could I not, though I’d never at all

ever heard of Slim Harpo

here’s Slim Harpo, he’s a treat

but a harmonica, finally, is too brash

an instrument to easily fashion out

of it love songs, so I’ll hold onto my

guitar

you’ll note that despite the entirely

different style of music from the

Classical stuff I’ve been bringing

up, the three essentials, tonality,

tempo, and reiteration still apply,

this trinity is the foundation of all

of our Western musical culture,

the output changes only according

to geographical place and time

within those European parameters

Asia has its own, indeed several,

distinct musical idioms

Slim‘s is manifestly the American

Deepest South

R ! chard

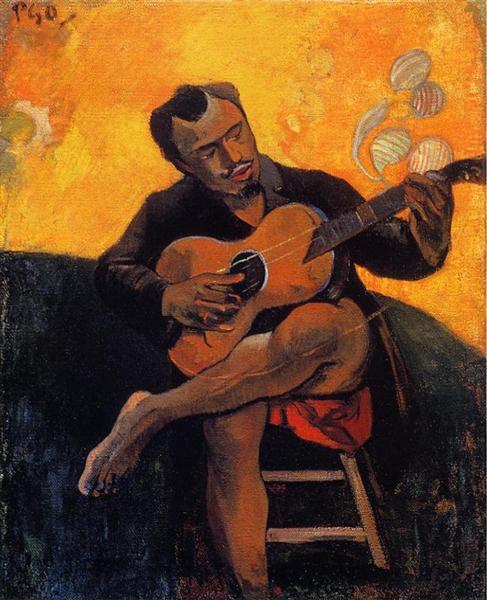

“The guitar player“ (1894)

________

for Daniel, despite his

occasional jabs

transcribed for guitar, Bach’s Cello Suite no 4

becomes an entirely other experience, listen

less transformationally, the original key, E flat,

is transcribed, altered, to the key of C, you

won’t even notice

from an introspective, however lively often,

utterance, I hear here, rather, a serenade,

before a balcony, before the balustrade of

a blushing señorita, demure beneath her

modest mantilla, quivering behind a

fluttering matching fan, at the sincerity,

and artistry of her courter, his

unadulterated, and utterly vulnerable

pursuit, an unmistakable expression of

his devotion, ability, agility, and eventually,

his worth, which is, incidentally, what art

is, when achieved, always irresistible, even

miraculous

plus who wouldn’t surrender everything

to this guitarist, apart even from his art

R ! chard