November / Month of the Sonata – 18

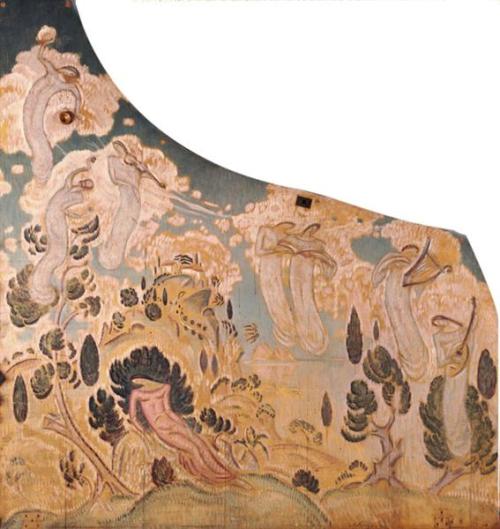

“The Birth of Venus” (1485)

___________

if there’s a piano concerto that dominates

the 19th Century, it’s Tchaikovsky’s First

Piano Concerto, not even Beethoven’s

Fifth, to my mind, matches its celebrity,

one thinks Romantic Period, one thinks

this iconic masterpiece

Tchaikovsky had the advantage of

absorbing not only Beethoven by this

point in history, but also Chopin, the

narrative power of the former, with

the mesmerizing textures of the latter,

what could go wrong but insufficient

genius

of which Tchaikovsky manifestly had

more than plenty, enough to verily

stop your breath

many towering performers have

challenged this concerto‘s peaks,

some even historically, you’ve

heard them, I won’t reiterate

but listen to what Yuja Wang does with

this challenge, and you tell me if she

doesn’t conquer its tribulations,

despite, or abetted by, her

controversial dress

she is a vixen, manifestly, at least in,

admittedly, her attire, but should a

vixen play as brilliantly, what does

one have to counter her provocative

presentation but her innate femininity,

her, too often castigated, female pulse,

something the world could do with a

lot more of

Venus, with all her allure, was goddess

for centuries before women were

obliterated from the dominant Christian

pantheon, the Father, the Son, the Holy,

I ask you, Ghost, with no equal female

foundational representative

Yuja Wang, a modern day Venus abetted

by her evident attendant muses, the

symbolic, here, orchestra, see above,

could play nude, as far as I’m concerned,

she’d still be transcendent, and I’m not

even heterosexual

girlfriend, I say, however proper, modest,

blushing, get a grip

not to mention that Tchaikovsky is also,

in this outing, once again, astounding

R ! chard

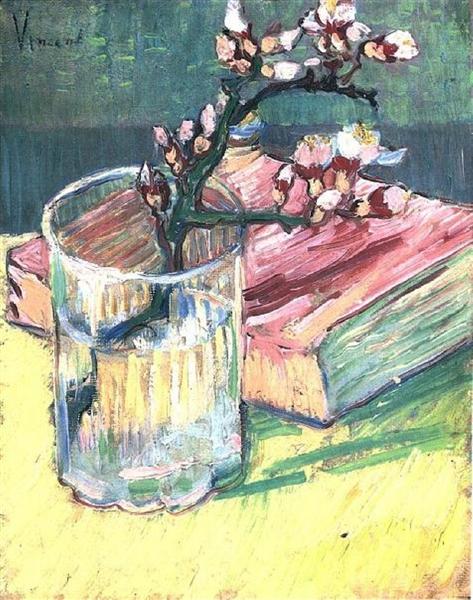

“Blossoming Almond Branch in a Glass with a Book“ (1888)

__________

if Tchaikovsky’s 2nd Piano Sonata hasn’t

remained in the canon, if it isn’t one of

the pieces you’ve heard if only through

the grapevine, it’s, I suspect, cause it’s

essentially not an advance on other more

prescient works in the form, other more

oracular compositions

Beethoven had paved the way for the

Romantic Period, nearly invented it,

established incontrovertibly the

dimensions of the sonata, notably its

purpose, its structure, Schubert had,

however belatedly, confirmed it, with

works equal to his, and even, here

and there, superior, listen

but having reached the summit of

what a sonata could say, the form

little by little withered in its several

Romantic permutations, Tchaikovsky

here, for example, and became mere

elaborations upon a waning theme

rather than exciting, and revelatory,

productions

the sonata would survive, but

transformed by another era,

Impressionism, Tchaikovsky would

as well, of course, but not through

his sonatas

his Second, however, is not not

worth a listen, would you pass,

for instance, on a less celebrated,

perhaps, van Gogh, see above

Tchaikovsky’s, therefore, Second

R ! chard