November / Month of the Sonata – 22

however endangered, species

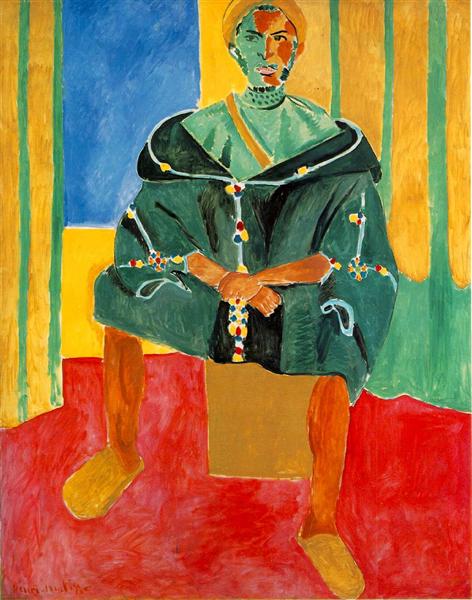

“The Violin“ (1916)

_____

if I was able to bring up a list of

ten top Romantic piano concertos

throughout the 19th Century earlier,

I can number of violin concertos

only three essential ones, with,

however, two other significant

such compositions, which remain,

for one reason or another,

peripheral, secondary

more about which later

but the exalted three are situated

conveniently, the first, at the very

beginning of the Romantic Era,

Beethoven’s magisterial, even

extraordinary, Opus 61 in D major,

1806, and close doubly with the

two others, Tchaikovsky’s

resplendent work, words cannot

do it justice, and Brahms’ no less

transcendental one, at its very end,

1878, none are negligible, it’d be

like missing the Eiffel Tower while

in Paris, skipping the pyramids

along the Nile, they are part of our

cultural consciousness, it would

be an utter shame to pass them

by, they are our glory, our

magnificent heritage

it should be noted that the

concerto, be it for violin, piano,

cello, what have you, a soloist

in concert with an array of

instruments, is the perfect allegory

for the Romantic Era, an individual

in contention with a community,

under the influence of a conductor,

a mayor, a mentor, a polity, the

individuality afforded by the

proclamation of human rights in

the aftermath of the French

Revolution, and its social

consequences, musically

manifested

the match might be fraught,

should be, though with

compromise, considerate

accommodation, fruitful,

hopefully even transcendental,

if not at least entertaining,

cooperation, music seems to

infer eventual concord,

congress, harmony, a way out

of, even dire, distress, or at

least point the way toward it

concertos die out, incidentally, in

the 20th Century, you don’t hear

of very many, if any at all, after

Rachmaninoff, they are gone,

much like later, in the 1950s, the

waltz, forever, with the wind

may they rest in peace

R ! chard

“Liberty Leading the People“ (1830)

_________

for everyone, with great gratitude,

who reads me, I mean only to

bring poetry, which is to say,

light

though I’d considered leaving the

Romantic Piano Concertos behind

to explore other areas of the period

in this survey, it seemed unfair,

indeed remiss of me, not to include

the three among my top ten that I

haven’t yet highlighted, Beethoven’s

2nd, 3rd, and 4th Piano Concertos,

Opuses 19, 37, and 58 respectively,

after all, these are where the spirit

of the age, the Zeitgeist, was

constructed, like a building, with

walls, windows, a hearth, all of

which would become a church,

then a Church, and by the time of

Brahms, a very Romantic Cathedral

the foundation had already been laid

by Mozart with his 27, but music had

not yet become anything other than

an entertainment by then, or

alternatively, an accessory to

ceremonial pomp and circumstance,

see Handel and England for this, or

liturgical stuff, see, among many

others here, Bach

but with the turn towards

independence of thought as the

Enlightenment progressed, cultural

power devolved from the prelates,

and their reverent representations,

to the nobles, who wanted their own

art, music, which is to say, something

secular, therefore the Classical

Period, 1750 – 1800, in round figures

then in the middle of all that, 1789,

the French Revolution happened,

and the field was ripe for prophets,

anyone with a message of hope,

and a metaphysical direction, midst

all the existential disarray – the Age

of Reason had set the way,

theoretically, for the possibility of a

world without God, something, or

Something, was needed to replace

the The Trinity, the Father, the Son,

and the Holy Ghost, Who had been

seeing Their supremacy contested

since already the Reformation

Beethoven turned out to be just

our man, don’t take my, but history‘s

authentification of it, see the very

Romantic Period for corroboration

in a word, Beethoven established a

Faith, a Vision, not to mention the

appropriate tools to instal this new

perspective, a sound, however

inherited, musical structure – his

Piano Concertos Two, Three, and

Four, for instance, are paramount

amongst a host of others of his

transcendental revelations

briefly, the initial voice, I am here, in

the first movement, is declamatory,

even imperious, but ever

compositionally solid, and proven,

tempo, tonality, recapitulation, the

materials haven’t changed from the

earlier Classical epoch, just the

design, the interior, the

metaphysical conception

his construction is masterfully

direct, the line of music is

throughout ever clear and concise,

despite flights of, often, ethereal,

even magical, speculation, you

don’t feel the music in your body

as you would in a dance, as in the

earlier era, of minuets, but follow

it, rather, with your intellect, you,

nearly irresistibly, read it

but the adagio, the slow movement,

the middle one Classically, is always,

for me, the clincher, the movement

that delivers the incontrovertible

humanity that gave power to the

Romantic poet, who touched you

where you live

Beethoven says life is difficult, and

eventually, at the end of his Early,

Middle and Late Periods, life may

even have no meaning

but should there be someone, he

says, who is listening, Someone –

though implicit is that one may be

speaking to merely the wind – this

is what I can do, this is who I am

and while I am here, however

briefly, I am not insignificant, I

can be worthy, even glorious,

even beautiful, I am no less

consequential, thus, nor

precious, than a flower

for better, of course, or for worse

R ! chard

Princess Friederike Luise of Prussia (1714-1784), Margravine of Brandenburg

____________

if you had trouble distinguishing your

Schubert from your Beethoven, you’ll

probably have trouble as well telling

your Mozart from your Haydn, though

you won’t find it difficult, if you listen,

to tell the earlier two from the latter

both the Haydn here, and the Mozart,

were written in 1789, the year of the

French Revolution, something akin

to our 9/11, the world changed from

one moment to the next

the first two were still doing parties,

which is to say, salon music, stuff

for elites, you can hear it, frivolities,

with, however magical, elaborations

– Liberace, I thought – nothing ever

as confessional as the two later

composers, who, with the new

fervour around individual opinion,

in the wake of questions even about

the validity of God, would create the

very Romantic Era

Mozart and Haydn explore songs,

ditties, Beethoven and Schubert

investigate very fundamental

musical constructions, they’re

down to the very essence of

tonal possibilities, something

that happened to the pictorial

arts in the 1950’s, as artists

probed the cerebral implications

of colour, see for instance,

Rothko

their probe itself becomes more

powerful than their apparent

subject, the tune, though the

melody proves to be, ever, the

cement that keeps the meditation

together

what it says, what they say, is

that confronting our destiny,

we remain the only arbiter, its

outcome will be as beautiful

as we make it, for better or for

worse, the creation of

something beautiful, a work

that can be so beautiful, much

like a life, seems to be a reply

that can somewhat, at least,

existentially satisfy a sense

of purpose

what, otherwise

R ! chard

psst: Mozart’s piano sonata was written

for Princess Friederike Luise of

Prussia, pictured above

though Beethoven’s piano sonata no 4,

in E flat major, opus 7 has never been

one of my favourites, I’m finding this

particular rendering completely

enchanting

the opus 7 is, of course, early, when

you consider Beethoven reached into

the late 130s for his opuses, his opera,

not counting his, as bountiful, WoOs,

works without opus numbers

the sonata is steeped in Classical

conditions that are becoming ossified

at this point, about a decade after the

French Revolution, 1796 – 7, and that

have yet to be culturally overturned,

put to rest, you can hear it, you hear

the Classical form – formality, repetition,

congenial tonalities still – in the sonata,

brilliantly displayed by a composer

of ripe and rich imagination, but at

the service of structure rather than

the music itself, style over substance,

a student’s musical submission for a

composition exam

you’ll hear the repeat of the opening air

in the first movement more times than

you think is necessary, though the tune

be ever jaunty, never unpleasant, just

essentially trite, the second movement,

is a largo, a largo indeed, you’ll think,

about to fall asleep, even, at the wheel,

the later movements keep you

entertained in most interpretations,

not much, however, inspired, music to

pass the time, to check your watch by,

it needs what Beethoven will later

deliver in spades, miracles and

majesty, conviction

the opus 7 is long as well, nearly

interminable, I think, second only in

length to the sublime however

“Hammerklavier“, the 106, impudent

therefore, to my mind, if not outright

arrogant, in the mode of lesser artists,

Salieri, Clementi, for instance, who

never manage to transcend their,

however impressive, technical

expertise

but in this commanding account –

maybe I’ve grown into the piece, or

maybe the performance itself is more

inspired – Joel Schoenhals finds

something that’s had me listen for

hours and hours, rapt, mesmerized

Richard

psst: I needed this sonata for a course

I’m taking at Coursera, an Internet

learning site, on the Beethoven

piano sonatas, the opus 7 is the

first one we’re looking at, this

performance was the best one I

could find