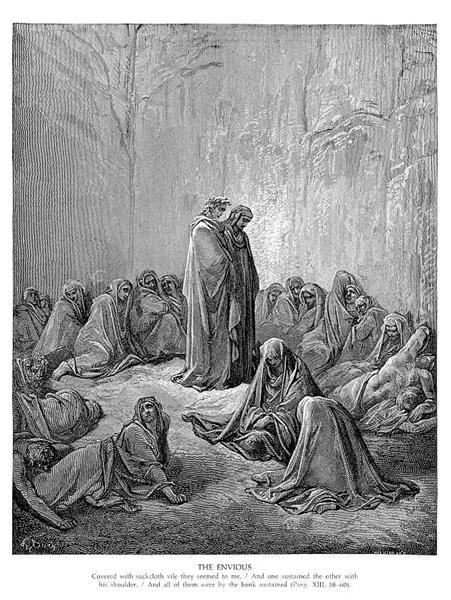

“The Story of Aglauros, transform’d into a Statue” (lll) – Ovid

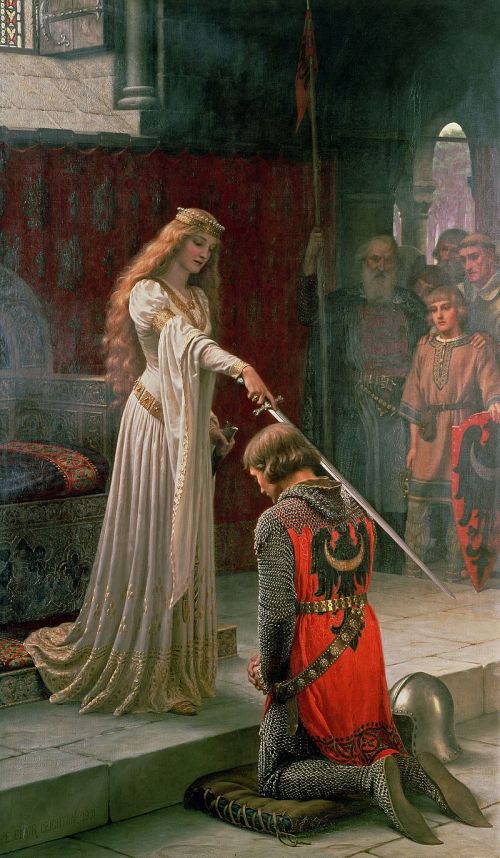

“The Accolade“ (1901)

___________

When you come to greet me, shyly,

wearing nothing but your love for me

I will come to meet you halfway

like a falcon returning to your wrist.

And when you raise your arm,

trembling ever so slightly,

I will alight and let you pull

the velvet shroud over my eyes.

—————–

courtly love, an idea of love that took

shape in the 12th Century in what would

become France eventually, though its

development soon touched all the

countries, or kingdoms then, of Europe,

became the primary subject of poetry

and literature especially through the

influence of Eleanor of Acquitaine,

without a doubt the most powerful

woman in Europe during her reign as

Queen of France after her marriage to

Louis Vll, which was annulled after a

time for her having not borne Louis

any sons, then with Henry, Duke of

Normandy, who then became Henry ll

of England, with whom she had

Richard l, the Lionheart, as well as the

later King John – the wonderful film,

“The Lion in Winter” with Katherine

Hepburn as Eleanor is a brilliant

account of her later life with Henry

and their fractious sons, featuring

as well Peter O’Toole as Henry, and a

young Anthony Hopkins as Richard

her patronage of the arts in general

then, from her position of power,

allowed, much as it would today any

potentate, the dissemination of

courtly love as a cultural ideal that

ultimately led to some of the greatest

works of our Western cultures, notably

Dante‘s “The Divine Comedy“, where

Dante courts chastely the married

Beatrice, who becomes indeed even

an intermediary for him during his

passage through Paradise

the idea, through the interpolation of

the Catholic Church, was that courtly

love should be pure, unconsummated,

a noble admiration and reverence of

an object of adulation within the strict

constraints of an impossible physical

conjunction, the model being, of course,

the emulation of the worship of the

Virgin Mary

Cervantes‘ “Don Quixote“ is a later

example of this same disposition,

though by this time, 1605 to 1615,

the practice of courtly love had

been sullied by too many evidently

corrupt practitioners, and a more

cynical therefore culture, so that

Don Quixote despite his blameless

pursuit of Dulcinea, his unwitting

muse, is made out to be a fool

given the context of his more

contentious times, albeit a benign,

and somewhat heroic, fool

but my very favourite such story is

that of Edmond Rostand‘s “Cyrano

de Bergerac“, whose long nose

makes him disparage his own

chances of ever achieving the love

of his beloved, Roxane

José Ferrer got an Oscar for his

superb performance of Cyrano in

1950, but my ideal remains that of

Gérard Dépardieu, a complete

wonder, in 1990, both very much,

however, worth your time

all this as a preface to the poem

above, When You Come, which

seems to me of that tradition,

despite having been written in

2014 according to its inclusion

then in the Literary Review of

Canada, perhaps because of the

introduction of the falcon, not at

all a contemporary image, but

fraught with the impression of a

love that is all devotion instead

of conquest, a kind of love that

in my particular circumstances

I’ve come to reach for rather

than anything less refined

true love, in other words, can

never not love, as I’ve said earlier

Richard