how to listen to music if you don’t know your Beethoven from your Bach, Vl

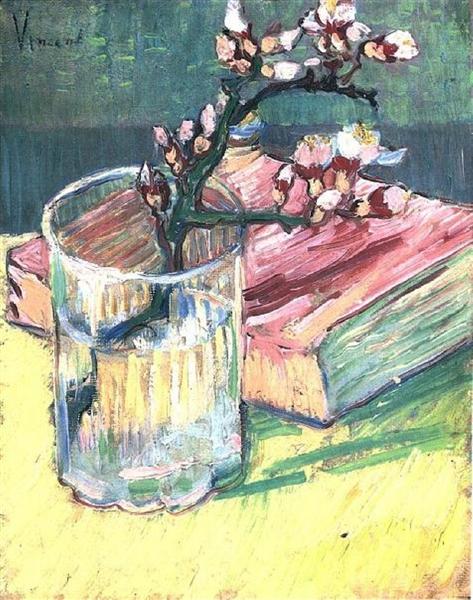

“Blossoming Almond Branch in a Glass with a Book“ (1888)

__________

if Tchaikovsky’s 2nd Piano Sonata hasn’t

remained in the canon, if it isn’t one of

the pieces you’ve heard if only through

the grapevine, it’s, I suspect, cause it’s

essentially not an advance on other more

prescient works in the form, other more

oracular compositions

Beethoven had paved the way for the

Romantic Period, nearly invented it,

established incontrovertibly the

dimensions of the sonata, notably its

purpose, its structure, Schubert had,

however belatedly, confirmed it, with

works equal to his, and even, here

and there, superior, listen

but having reached the summit of

what a sonata could say, the form

little by little withered in its several

Romantic permutations, Tchaikovsky

here, for example, and became mere

elaborations upon a waning theme

rather than exciting, and revelatory,

productions

the sonata would survive, but

transformed by another era,

Impressionism, Tchaikovsky would

as well, of course, but not through

his sonatas

his Second, however, is not not

worth a listen, would you pass,

for instance, on a less celebrated,

perhaps, van Gogh, see above

Tchaikovsky’s, therefore, Second

R ! chard

“Queen Marie Antoinette of France“ (1783)

Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun

___________________

first of all, let me grievously repent an

egregious confusion I probably left

in my last diatribe, I said that the second

movement of the Opus 54, no 2 sounded

to me like a minuet, I had, through

embarrassing inattention, confused its,

however unmemorable, adagio with that

of this Opus 55, no 3, which I’d listened

to in too quick succession, driven as I

am by my thirst for epiphanies

the Opus 54, no 2 will do, but I’m not

going back for seconds, nor to the

Opus 55, no 3, though here’s where

I flaunt nevertheless Haydn, not to

mention Bach, Mozart, Beethoven,

all the way to eventually Bruckner,

Brahms, the extraordinary Richard

Wagner, passing through Schubert,

Mendelssohn, the Strausses, father

and son, and the unrelated Strauss,

Richard, another incontrovertible

giant, and I nearly left out the

unforgettable Liszt, all of them

forefathers of our present music

you might have noticed that these

are all Germanic names, obedient

to the Hapsburg empire, with

Vienna as its supreme cultural

capital, and it was that

Austro-Hungarian dynasty that

indeed nearly single-handedly

secured our Western musical

traditions

a few Italians are remembered,

from the 18th Century, Scarlatti

maybe, Boccherini, Albinoni,

but not many more

no one from France, but they were

about to have a revolution, not a

good time for creative types,

though, incidentally, Haydn was

getting Tost, to whom he was

dedicating his string quartets for

services rendered, to sell his stuff

in very Paris

then again, Marie Antoinette, I thought,

was Austrian, an even archduchess,

and would’ve loved some down-home

music at nearby Versailles

so there you are, there would’ve been

a market

the English had Handel, of course,

who was, albeit, German, getting

work where he could when you

consider his competition, he was

too solemn and plodding by half,

to my mind, for the more

effervescent, admittedly Italianate,

continentals, Italy having led the

way earlier with especially its

filigreed and unfettered operas

but here’s Haydn’s Opus 55, no 3

nevertheless, the best Europe had

to offer, socking it to them

Haydn’s having a hard time, I think,

moving from music for at court to

recital hall music, music for a much

less genteel clientele, however

socially aspiring, we still hear

minuets, and obeisances all over

the place, despite a desire to

nevertheless dazzle, impress

then again, I’m not the final word, as

my mea culpa above might express,

you’ll find what eventually turns

your own crank, floats your own

boat, as you listen

which, finally, is my greatest wish

R ! chard

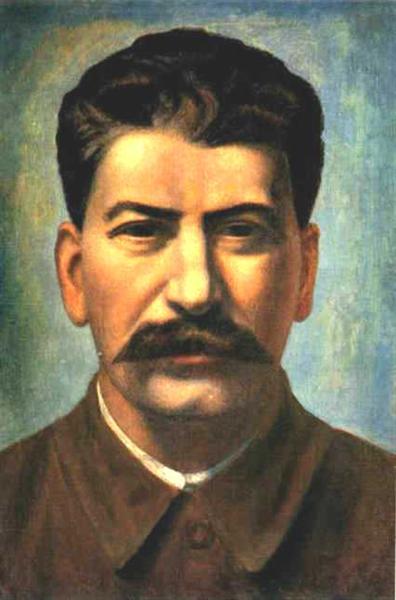

“Portrait of Joseph Stalin (Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili)“ (1936)

_________

if you’ve been waiting for a Shostakovich

to write home about among his early

symphonies, here’s the one, his

Symphony no 4 in C minor, opus 43 will

knock your socks off from its very

opening gambit, have a seat, settle in,

and get ready for an explosive hour

the Fourth was written in 1936, some

years after the death of Lenin, and the

instalment of Stalin as the supreme,

and ruthless, authority, after several

years throughout the Twenties of

maneuvering himself, cold-bloodedly,

into that position

from Stalin, “Death is the solution to

all problems. No man – no problem.“

fearing retribution after Stalin had

criticized his recent opera, “Lady

Macbeth of Mtsensk“, Shostakovich

cancelled the first performance of

this new work, due to take place in

December, ’36, others had already

suffered internal exile or execution

who had displeased the tyrant, a

prelude to the infamous Great Terror

the Symphony was eventually played

in 1961, 25 years later, conducted by

no less than Kirill Kondrashin, who’d

partnered Van Cliburn a few years

earlier in Cliburn’s conquest of Russia,

but along with this time however the

long-lived Leningrad Philharmonic

Orchestra

to a friend, I said, this is the biggest

thing since verily Beethoven, no one

has so blown me away symphonically

since then

he looked forward, he replied, to

hearing it

the Fourth Symphony has three distinct

movements, to fit thus appropriately the

definition of symphony, though the first

and third have more than one section,

something Shostakovich would have

learned from already Beethoven, it gives

the opportunity of experiencing a variety

of emotions within one uninterrupted

context, add several movements and

you have a poignant, peripatetic musical

journey, more intricate, psychologically

complex, than many other even eminent

composers, Schubert, Chopin,

Mendelssohn, even Brahms, for instance

it’s helpful to think of film scores, and

their multiple narrative incidents,

brimming with impassioned moments,

however disparate, Shostakovich had

already written several of them

let me point out that Shostakovich’s

rhythms are entirely Classical, even

folkloric in their essential aspects,

everywhere sounds like a march,

proud and bombastic, if not a

veritable dance, peasants carousing,

courtiers waltzing, and repetition is

sufficiently present to not not

recognize the essential music

according to our most elementary

preconceptions

but the dissonances clash, as though

somewhere the tune, despite its rigid

rhythms, falls apart in execution, as

though the participants had, I think,

broken limbs, despite the indomitable

Russian spirit

this is what Shostakovich is all about,

you’ll hear him as we move along

objecting, however surreptitiously,

cautiously, to the Soviet system, like

Pasternak, like Solzhenitsyn, without

ever, like them, leaving his country

despite its manifest oppression, and

despite the lure of Western accolades,

Nobel prizes, for instance, it was their

home

and there is so much more to tell, but

first of all, listen

R ! chard

the “Waldstein” Sonata, no. 21 in C major, opus 53, is

one of the few compositions that Beethoven named

himself, which is to say that he dedicated it to a

friend and patron, Count Ferdinand Ernst Gabriel

von Waldstein, if you can call that naming it

the ones with descriptive titles, the “Moonlight”, the

“Pastorale“, “The Hunt“, for instance, were mostly so

labeled by his publisher for ease of identification in

the growing market place, a more affluent merchant

class eager to take on the refinements of the nobles,

see such an instance of social mobility, however

lampooned, updated and upended, in again the

engaging and not at all unperceptive “The Beverly

Hillbillies“

this means that the suggestive names we’ve come

to associate with his sonatas, “Moonlight”, “Pastorale“,

“The Hunt“, were never conceived as such by

Beethoven, his compositions were ever purely musical

inventions, or more accurately inspirations, prophetic

pronouncements of a much more oracular order,

like Prometheus Beethoven was delivering nothing

short of fire

to match music to specific visual, or even emotive,

cues, incidentally, “Pictures at an Exhibition“,

“The Carnival of the Animals“, for example, came

later, already a nod to Beethoven’s even indirect

propositions

that titles were given to music, rather than the more

clinical and mnemonically difficult numbers, which

is to say, not easy to remember, isn’t very different

from the evolution of popular music in the early

1960′s

the Beatles, you’ll remember, had cuts on albums

that had nothing more than their group name in

the titles, or the title of one of the album’s cuts,

“Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” came

along to change all that, we saw the birth of the

concept album, where the whole extended affair

becomes a musical metaphysics, this is no

different from the move from the music of Mozart

to that of the more expansive Beethoven, music

is no longer a ditty but an extended technical

and philosophical text, listen to Pink Floyd take

on this mantle superbly in the Seventies, the only

other body since ever to effectively challenge

Beethoven in that especially rarefied field, with

the probable exception of the sublimely expressive

Schubert perhaps, who died much too young for us

to tell, for him to have decisively dialectically proven

himself beside these erudite peers, all having,

however, found ways to have us touch beyond the

sky, the very infinite, and into the no less infinite

confines of our more private and secret selves

what they state is that creation itself, absent any

other meaning, remains potent, perhaps even

ultimately redemptive

creation as a bold and noble response to eternity,

art as affirmation

you’ll note here that the structure of this sonata

is entirely Classical, unity of tone, unity of pace,

and the eventual return of the initial melody,

essential Classical components, what has

changed is the personal bravura of the composer,

Beethoven is not playing for the aristocratic court,

but for a wider, an infinite, audience, he is

pronouncing his and, by extension, our own place

and validity in the universe, by our ability as humans

to create, to respond creatively, and even sublimely,

out of only our otherwise flailing and indeterminate

existence

it is the Romantic response to the waning belief

in God, and incidentally a profound spur to,

argument for, our present notion of inalienable

individual rights

the personal soul has taken over from the earlier

unchallenged deity, the wavering concept of God

has had a seismic fall, and all the king’s horses

and all the king’s men will never be able to put it

together undiminished again

Beethoven is showing us that future

Richard

psst: Helena Bonham Carter plays excerpts from the

“Waldstein“, incidentally, in “A Room with A View“,

a movie entirely worth a revisit

“A portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven“ (1820)

_____________

you might say a triumvirate of piano concertos dominate

our Western musical culture, a veritable trinity of pianistic

masterworks that tower over, and have ruled, our musical

consciousness throughout the modern epoch, the

Rachmaninoff 3 has been one of them, but the 5th of

Beethoven is surely the granddaddy, the “Guppa” as a

favourite grandchild I know would say, the Olympian

Zeus, the Christian God the Father, of them all, in majesty

and authority, others quake in its overwhelming aura, it is

the sun to all the other stars

Glenn Gould is the standard still by which it should be

played, none yet, to my mind, has surpassed him

Karel Ancerl conducts the Toronto Symphony Orchestra,

a competent orchestration, overshadowed inevitably by

this prodigy, who nevertheless doesn’t ever flaunt his

finger play but remains faithful throughout to the

dictates, the tonal balances, of the music, it is 1972

I had mentioned “variations in volume, tempo, tonality,

the play of harmonization and discords” in Rachmaninoff,

note the strict adherence to tempo here, even the fastest

runs of notes are grounded in beat, more solid, less elusive

than the iridescent Rachmaninoffian allusions to Debussy,

you could set a metronome to the appropriate tempo of

each individual movement in Beethoven, it would remain

constant, apart from a few restrained ritardandos near

the end of some musical elaborations, until its very final

apotheosis, beat was ever an anchor for the fulgurating

Beethoven, an article of faith from which he strayed only

with great circumspection

note the language is not emotional, passionate and ardent,

but philosophical, metaphysical, Beethoven is confronting

cosmological considerations, existential realities, not the

more emotional concerns that confound us every day, it’s

God he’s talking to, eternity, not the incarnate tendrils

of the moment, not the poignant stuff even of soon

through Schubert a Chopin, Beethoven was at the start

of that Romantic Movement, indeed its very first

proponent, but not quite ready to wear his heart itself

on his sleeve, but a more spiritual, probing reason, whose

ardent metaphysical ratiocinations would set all the others

on fire, setting the stage for all the other stars

later, if you haven’t guessed what it’ll be already, I’ll

supply you with the third concerto, the Holy Ghost, of

the trinity, the Apollo, god of music and the sun, among

our concert greats

Richard