perhaps my best teacher ever was

my father, others never questioned

the orthodoxy, spewing out the

curriculum like it was sacred, dead,

untouchable, depriving it of its very

worth

my father was a philosopher, God

was a question, not an answer, I,

at the time, needed an answer

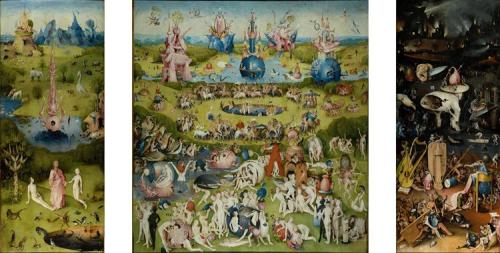

we were sent to a Catholic school,

my sister and I, where God was in

everything, everywhere, omnipotent,

omniscient, and, like a father then,

autocratic, industrious, demanding,

not unopposed to punishment

sins against the Father could be

summarized, at that age, briefly,

do not kill, do not lie, do not

disobey your parents, do not

cheat on your husband, wife,

and follow all the rituals of the

Church, the Ten Christian

Commandments, brought to

“Moses” Heston, under the aegis

none of these graded offences

applied to me, really, then, but

lying, and disobeying one’s

parents, the others were all so

remote as to be inconsequential,

though the Church kept up on

our family’s abrogations of

religious rites – non-attendance

at Sunday mass, eating meat

on Fridays, worse – while

nevertheless tending dutifully

to our wayward souls, they told

us, holding out for a final repentant

confession

we never lied at home, I’d lied about

something once, and was so daunted

when my father probed, I sweated,

must’ve turned purple, not just red,

of embarrassment, I knew I couldn’t

use that tactic again, I’d inexorably

blush, flush

he’d queried

not me, I trembled

my sister stood beside me, might

not have even known anything

about it, I can’t remember, though

I recall her dismay, I think, at having

been so blithely thrown under the

bus, or maybe that’s just me

extrapolating

my dad turned back to what he’d

been doing, having, I’d understood,

got his answer, proving himself to

be to me thereby omniscient, I’d

have no chance, I gathered, against

something like that, this turned me

into a good, an at least conscientious,

person

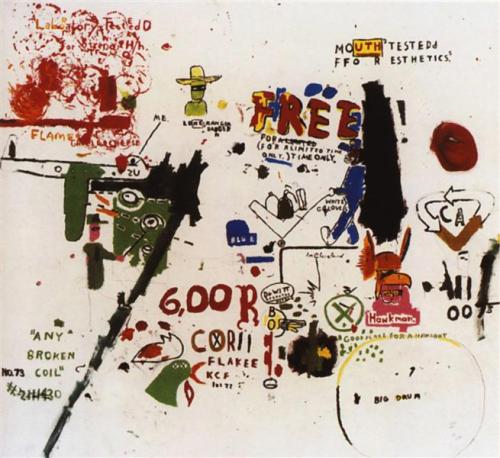

my teachers, paradoxically, only

ever took marks off for technical

stuff, Math, History, French, they

never taught me lessons

a teacher, once, had asked me to

stand at the head of the class and

read a passage from Shakespeare,

be Romeo, Mark Antony, Lear, I

can’t remember which

“O, pardon me, thou bleeding

piece of earth, / That I am meek

and gentle with these butchers!”,

I uttered, fraught with emotion,

“Thou art the ruins of the noblest

man / That ever lived in the tide

of times”

in my mind and in my body I was

Mark Antony there, shot through

with the weight of his friend’s

brutal death, his own irretrievable

loss

my teacher laughed

what, I asked

you’re right into it, aren’t you, he

replied, and shut me up right there

to any public display of expression

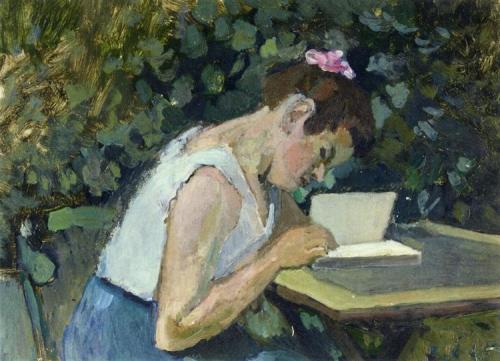

I didn’t stop reading Shakespeare

though, but by myself

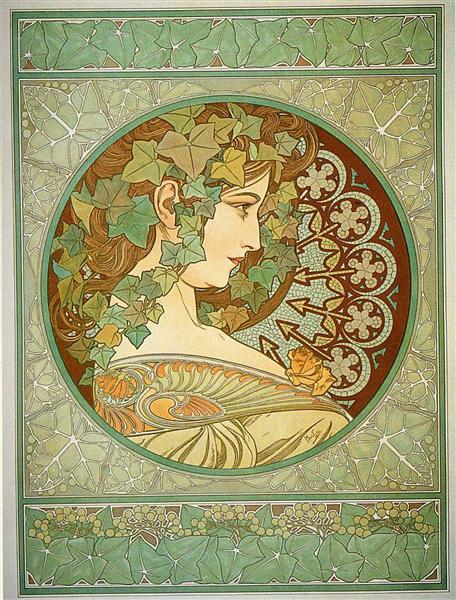

later I read Homer, Ovid, Proust,

others, did the same with music

and art, made countless lifelong

friends thereby, people I’ve always

been able to turn to, even just in

ruminative thought as their stories

still pervaded me, diligently leading

still the way, like guardian angels,

maybe

Richard