String Quartet in B flat, Opus 55, no 3 – Haydn

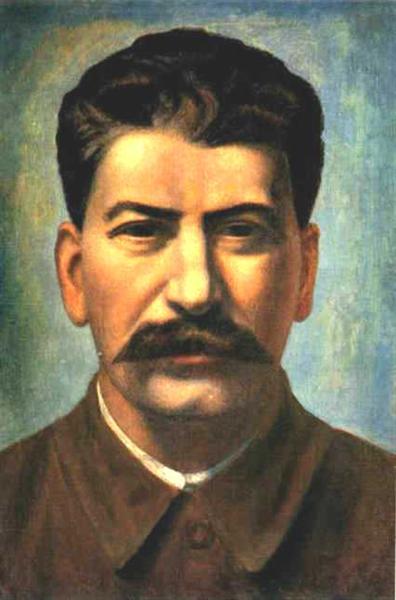

“Queen Marie Antoinette of France“ (1783)

Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun

___________________

first of all, let me grievously repent an

egregious confusion I probably left

in my last diatribe, I said that the second

movement of the Opus 54, no 2 sounded

to me like a minuet, I had, through

embarrassing inattention, confused its,

however unmemorable, adagio with that

of this Opus 55, no 3, which I’d listened

to in too quick succession, driven as I

am by my thirst for epiphanies

the Opus 54, no 2 will do, but I’m not

going back for seconds, nor to the

Opus 55, no 3, though here’s where

I flaunt nevertheless Haydn, not to

mention Bach, Mozart, Beethoven,

all the way to eventually Bruckner,

Brahms, the extraordinary Richard

Wagner, passing through Schubert,

Mendelssohn, the Strausses, father

and son, and the unrelated Strauss,

Richard, another incontrovertible

giant, and I nearly left out the

unforgettable Liszt, all of them

forefathers of our present music

you might have noticed that these

are all Germanic names, obedient

to the Hapsburg empire, with

Vienna as its supreme cultural

capital, and it was that

Austro-Hungarian dynasty that

indeed nearly single-handedly

secured our Western musical

traditions

a few Italians are remembered,

from the 18th Century, Scarlatti

maybe, Boccherini, Albinoni,

but not many more

no one from France, but they were

about to have a revolution, not a

good time for creative types,

though, incidentally, Haydn was

getting Tost, to whom he was

dedicating his string quartets for

services rendered, to sell his stuff

in very Paris

then again, Marie Antoinette, I thought,

was Austrian, an even archduchess,

and would’ve loved some down-home

music at nearby Versailles

so there you are, there would’ve been

a market

the English had Handel, of course,

who was, albeit, German, getting

work where he could when you

consider his competition, he was

too solemn and plodding by half,

to my mind, for the more

effervescent, admittedly Italianate,

continentals, Italy having led the

way earlier with especially its

filigreed and unfettered operas

but here’s Haydn’s Opus 55, no 3

nevertheless, the best Europe had

to offer, socking it to them

Haydn’s having a hard time, I think,

moving from music for at court to

recital hall music, music for a much

less genteel clientele, however

socially aspiring, we still hear

minuets, and obeisances all over

the place, despite a desire to

nevertheless dazzle, impress

then again, I’m not the final word, as

my mea culpa above might express,

you’ll find what eventually turns

your own crank, floats your own

boat, as you listen

which, finally, is my greatest wish

R ! chard