Dmitri Shostakovich – “Symphony No 4” in C minor, opus 43

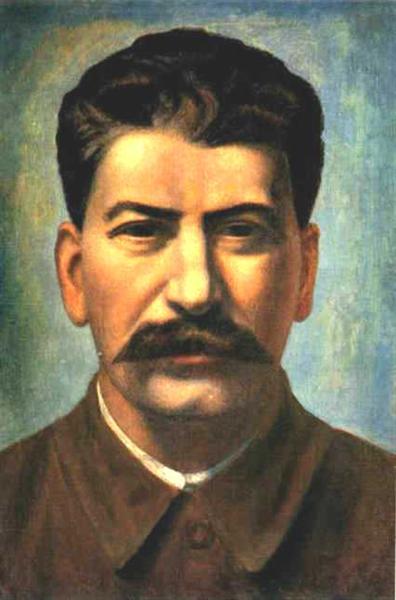

“Portrait of Joseph Stalin (Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili)“ (1936)

_________

if you’ve been waiting for a Shostakovich

to write home about among his early

symphonies, here’s the one, his

Symphony no 4 in C minor, opus 43 will

knock your socks off from its very

opening gambit, have a seat, settle in,

and get ready for an explosive hour

the Fourth was written in 1936, some

years after the death of Lenin, and the

instalment of Stalin as the supreme,

and ruthless, authority, after several

years throughout the Twenties of

maneuvering himself, cold-bloodedly,

into that position

from Stalin, “Death is the solution to

all problems. No man – no problem.“

fearing retribution after Stalin had

criticized his recent opera, “Lady

Macbeth of Mtsensk“, Shostakovich

cancelled the first performance of

this new work, due to take place in

December, ’36, others had already

suffered internal exile or execution

who had displeased the tyrant, a

prelude to the infamous Great Terror

the Symphony was eventually played

in 1961, 25 years later, conducted by

no less than Kirill Kondrashin, who’d

partnered Van Cliburn a few years

earlier in Cliburn’s conquest of Russia,

but along with this time however the

long-lived Leningrad Philharmonic

Orchestra

to a friend, I said, this is the biggest

thing since verily Beethoven, no one

has so blown me away symphonically

since then

he looked forward, he replied, to

hearing it

the Fourth Symphony has three distinct

movements, to fit thus appropriately the

definition of symphony, though the first

and third have more than one section,

something Shostakovich would have

learned from already Beethoven, it gives

the opportunity of experiencing a variety

of emotions within one uninterrupted

context, add several movements and

you have a poignant, peripatetic musical

journey, more intricate, psychologically

complex, than many other even eminent

composers, Schubert, Chopin,

Mendelssohn, even Brahms, for instance

it’s helpful to think of film scores, and

their multiple narrative incidents,

brimming with impassioned moments,

however disparate, Shostakovich had

already written several of them

let me point out that Shostakovich’s

rhythms are entirely Classical, even

folkloric in their essential aspects,

everywhere sounds like a march,

proud and bombastic, if not a

veritable dance, peasants carousing,

courtiers waltzing, and repetition is

sufficiently present to not not

recognize the essential music

according to our most elementary

preconceptions

but the dissonances clash, as though

somewhere the tune, despite its rigid

rhythms, falls apart in execution, as

though the participants had, I think,

broken limbs, despite the indomitable

Russian spirit

this is what Shostakovich is all about,

you’ll hear him as we move along

objecting, however surreptitiously,

cautiously, to the Soviet system, like

Pasternak, like Solzhenitsyn, without

ever, like them, leaving his country

despite its manifest oppression, and

despite the lure of Western accolades,

Nobel prizes, for instance, it was their

home

and there is so much more to tell, but

first of all, listen

R ! chard