______

while we’re on the subject of études, listening to

hundred years later, 1830s to 1915, would prove

instructive, I deemed

picture me deeming, August 3, 2012, my brow

just slightly pensively constricting

if the basis of music as defined by the Classical

period depended on beat, tonality, and the repetition

of the tune, usually of both musical statements, these

apparently essential components of course would be

the first places to bear the scrutiny of probing musical

minds, seeking to find, seeking to set more expansive,

more profound dimensions to the areas of their quest,

that’s what artists do

and this of course is exactly what happened starting

with Beethoven, by the time of Chopin music had

relaxed its stricter Classical rhythmic precision,

allowing great expansive gestures in the more

malleable tempi, tempos, producing the effect of

more compassion and soulful examination than

the earlier less indulgent, more disciplined code

the fact of having musical tapestries, sound patches,

take the place of melody, narrative, in the musical

presentation of Chopin also suggests a more

diversified, dare I say prismatic, telling, than the

linear account of for instance Mozart‘s solitary

tuneful wanderer

it also evokes incidentally the vagaries of the

inconstant heart rather than its unflinching

condemnation, a repudiation of atavistic

Christian ecclesiastical intolerance

by the time the old order was about to be extinguished,

in 1915, at the onset of the First World War, Debussy’s

“Études“, like Chopin 12 of them per set, had seen

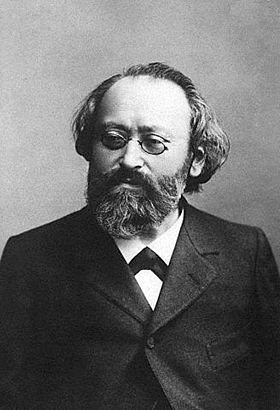

social injustice – see Charles Dickens, see Émile Zola,

see Karl Marx – the improbable discoveries of science –

Darwin, Freud, Einstein – the car, the airplane,

photography were changing everything, the old

paradigms no longer applied, were irrelevant, even

harmful, in this new context, the First World War

would prove all that

in the language of music, tempo, melody, repetition

would be inevitably subverted

Debussy produces erratic tempi, foregoes melody for

harmonic exploration, combining incidentally the

musical patches of Chopin with the intellectually

driven investigations of Beethoven for a more

cerebral understanding of music, a music for the

head, with expert displays of pianistic skill, indeed

prestidigitation, for, along with the intellectual

rigour, spectacle

is this then still music

is Post-Impressionist painting still art

what would 1915 have said

man with a guitar, who’d a thunk it

Richard