Piano Concerto no 4, Opus 58 – Beethoven

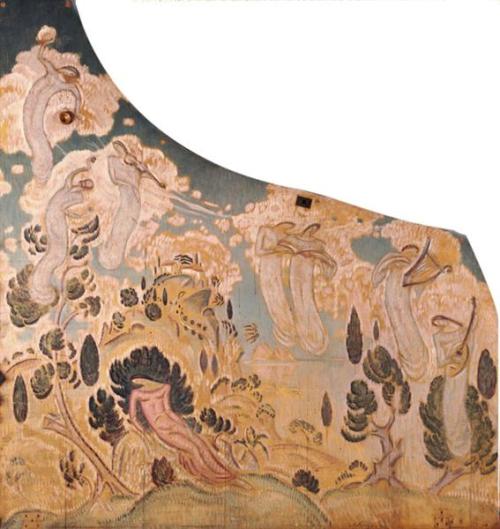

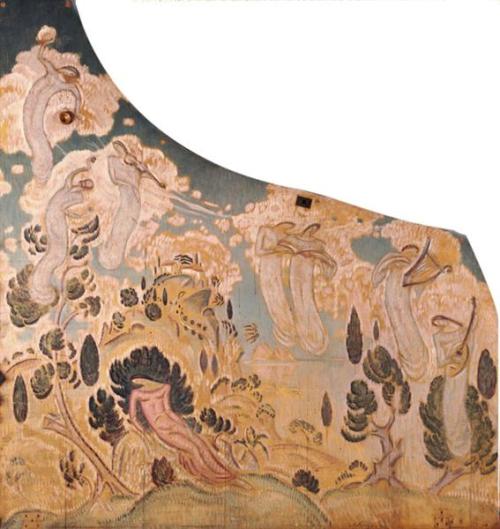

“Ophelia“ (1889)

___________

though death is not an especially

appealing topic for many, it was

nevertheless of fundamental

consideration during the

Romantic Period

Goethe, the German poet, had

already created a sensation

with his “The Sorrows of Young

Werther“, a young man,

disappointed in love, takes his

own life, a potent seed for the

new era, secularism was

overtaking theocracy, the

autocracy of the Christian

Church was giving way to the

prevalence of human rights,

a private opinion, well disputed,

was holding sway against the

rigidities of religious orthodoxies,

science and reason had been

chipping away at the very idea

of God

but with human rights there was

the question of personal

responsibility, if not an imposed

authority, then each man, woman

was in charge of his, her own

the fundamental question,

therefore, was Shakespeare’s

“To be or not to be“, or, for that

matter, Burt Bacharach’s and

Hal David’s “What’s it all about“

this is not me, this is Albert Camus

talking, who formalized the situation

in the 1940s

“There is but one truly serious

philosophical problem, and that

is suicide. Judging whether life

is or is not worth living amounts

to answering the fundamental

question of philosophy. All the

rest — whether or not the world

has three dimensions, whether

the mind has nine or twelve

categories — comes afterwards.”

after Werther, Madame Bovary followed,

Anna Karenina, suicide had become an

option, the penalty was no longer

opprobrium, castigation, as it had been

under unforgiving religious constraints

death itself, fatefully rather than

personally determined, was, of course,

no less considered when the era of

heartfelt declarations dominated,

Mendelssohn had written his

“Quartet no 6 in F minor, opus 80”

for his deceased sister, Beethoven

and Chopin, each his “Funeral March“,

either, incidentally, still iconic, and

perhaps the most poignant work

of all in this manner, Schubert’s

“Death and the Maiden“, a precursor

of his own much too premature

demise

this is music as if your life depended

on it

Richard

psst:

the Alban Berg Quartet, a group who

set the standard for several significant

string quartets in the ’80s, do no less

with this one

you’re not likely to see a better

performance of it ever, nor, for that

matter, of anything, pace even Glenn

Gould, a statement I think nearly

against my religion

you be the judge