Piano Concerto no 4, Opus 58 – Beethoven

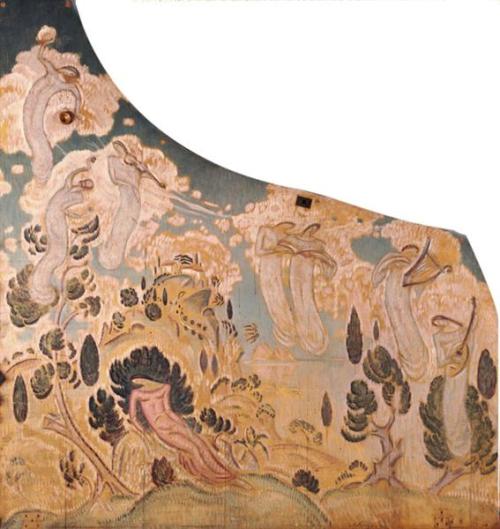

“The Minuet“ (1866)

_________

having pointed out that the minuet

and the waltz were historically

related, let me somewhat

extrapolate

they are both in 3/4 time, which is

to say, three quarter-notes to the

bar, which means that when

you’re dancing, your beat is one,

two, three, one two three, with

the accent, usually, on the first

note

so what happened, how could two

identical frameworks turn out so

differently

here’s Bach, 1725, his Minuet in G

the first thing you’ll think is, o, so

that’s what that is, it is an iconic

number written on our collective

consciousness

the second thing you’ll notice is

that it is choppy, however delightful,

that it is written for a harpsichord,

and that it’s probably not ready,

despite it’s 3/4 time, to be a waltz,

too many curtsies

here’s Mozart, 1762, his Minuet in G

though you might not want to admit

it, I suspect this number is much

more present in your subconscious

than you’d think, see if you don’t

find yourself later on humming it

but it’s still way too polite to be a

waltz, you can easily imagine the

partners, hands held high together

around their imaginary maypole,

courting, but there’s a touch more

fluidity in the progression of the

notes, it is written for a fortepiano,

an instrument that has added the

hold, or the sustain, pedal to the

harpsichord to increase a note’s

resonance, a loosening of the

earlier constraints of that

quintessentially Baroque

instrument, a cannily apt

metaphor, take into account, for

the unfolding cultural r/evolution

here’s Beethoven, 1796, his Minuet

in G, you’ve heard this one too

the Revolution has taken place,

but entrenched in the music of an

earlier era, the beat remains the

same, this is not a waltz, despite

it’s 3/4 progression

you’ll note, however, more spin

to the cadences, more give, more

elasticity, much of this has to do

with the development of the

central instrument, which was

about to become a pianoforte,

instead of a fortepiano, but

‘nough said about that, I’ll let

you feel it

here’s Chopin, 1833, his Grande

valse brillante, Opus 18, written

for itself, the piano, it is indeed

a waltz, the difference is in the

piano’s ever evolving flexibility,

again a metaphorical expression

of, or an avatar for, the unleashing

of personal freedom, an idea spun

ineradicably from the lessons of

the French, and the, incidentally,

nearly simultaneous, 1776, 1789,

American Revolutions

for better or for worse

R ! chard

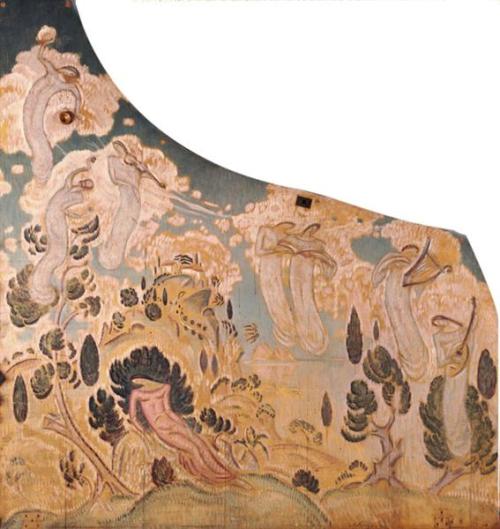

“Queen Marie Antoinette of France“ (1783)

Louise Elisabeth Vigee Le Brun

______________

if Mozart’s 19th String Quartet, the last of

his Haydn Quartets, the six he indeed

dedicated to Haydn, sounds less

deferential than one would have thought

for the period, it should be remembered

that the American Revolution had just

taken place, in 1776, the French one was

about to, in 1789, and even the more

aristocratic houses in Europe would not

have been unaffected, Mozart was young,

29, and astir with confidence and bravura,

it was 1785

Haydn had had his moment earlier, his

Opus 20, which went on to revolutionize

music if not countries, but had retreated

to a less emboldened political stance

as he grew older, while concentrating

rather on his more important muse, and

refining his ear for precise, pure music,

which is to say devoid of any but polite

sentiments, delight and lyrical

melancholy only

in Mozart’s 19th String Quartet, even the

minuet is peremptory, not something

you’d especially want to dance to,

however musically accomplished

he starts the first movement with, of all

things, an adagio, however briefly, which

could’ve been disastrous, you need to

know what you’re doing when you open

with a lament

incidentally, all the instruments in the

opening adagio are playing in different

keys, resolved when the allegro kicks

in, this is why it’s called “Dissonance”,

something in and of itself of a

rebellious act

the 19th is also twice the length of

Haydn’s nearest earlier one, his Opus 42,

expansive rather than terse, for whatever

that might mean, the point is to keep us

throughout interested, which he does,

they do

Mozart is prefiguring here, incidentally,

Beethoven, with his audacity, his

sense of an ideological mission, and

he’s mightily impressive

R ! chard