Richibi’s Weblog

Tag: Classicism

April 23, 2024

a veritable Schubertiade, VI

by this time, in his Piano Sonata in A minor,

D 845, Schubert has accumulated so much

Beethoven that his Beethoven is beginning

to shine through in his own compositions,

Beethoven was a forefather, still present,

it’s often difficult to tell one, indeed, from

the other, even here

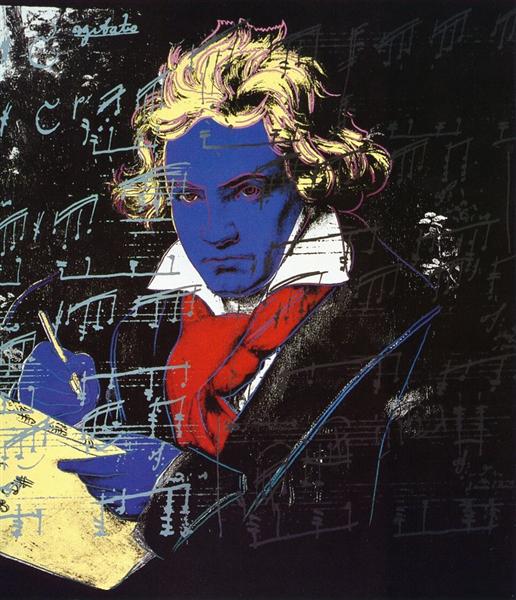

Beethoven, see above, punched through

Classicism – Mozart, Haydn – its artificiality,

delivering emotion, instinctively, from the

very start, from which he nearly

single-handedly delivered to the world no

less than Romanticism, like delivering the

recalibration of time and space after

Einstein essentially, so profound a

cultural metaphysical reorganization

Schubert remains ever more courteous,

more beholden to the upper crust that

supports him, and that he ever wants to

court, you can hear it, listen, there is no

confrontation here, just, dare I say,

entertainment

Schubert was not a revolutionary

R ! chard

June 5, 2018

twice upon a dirge – Beethoven / Chopin

“Owl on a Grave” / “Eule am Grab“ (c.1836 – c.1837)

_______

following my nose rather than

my intellect in my exploration

of musical treasures, like a very

Aladdin uncovering at the click

of my password a cave full of

priceless wonders, I might find

stuff out of sequence, but gems

nevertheless, and I can’t just

whisk by without acknowledging

them, however peripheral to my

main task

it’s like heading towards the Eiffel

Tower in Paris, and not stopping

at the Arche de Triomphe

though I’d debated so soon

presenting these two pieces,

not because of their chronology

especially, though also that, but

mostly because of their dour

content, I’ll point out that the

move from Classicism to

Romanticism is the transition

from dance music, delightful

music, to drama, passion,

powerful emotions, dirges,

therefore, are not out of place,

however mournful

thus the two most famous

funeral marches, Beethoven’s,

Chopin’s, the third movement

in either of their home sonatas

the clincher for me was the

immaculate performance of

the Chopin here, a revelatory

moment, though the Beethoven,

significantly earlier, the tune,

1801, 1837, is nevertheless

unimpeachable, however still

underdeveloped – four variations

only in the first movement, for

instance, and all of them

elementary – the caterpillar had

not yet become the butterfly, the

apple blossom the apple

note that each movement in the

Chopin, apart from the last, has

two distinct tempi, executed

effortlessly and nearly

imperceptibly, a total of six, you

can’t see, you can’t hear, the

seams as you listen, which, with

its virtual therefore episodes,

conflicting and tortuous

emotions, constitute collectively

a drama, a narrative, music has

become literature

the last movement of the Chopin

moves beyond even tempo –

Beethoven’s also, incidentally,

nearly – creating therefore a

very challenge to it, both trying

to transcend tempi, an area to

closely watch

Beethoven’s Piano Sonata no 12

take your pick

both are supremely, mark,

instructive

R ! chard

March 4, 2018

String Quartet, opus 77, no 1 – Joseph Haydn

“The Red Cape (Madame Monet)“ (c.1870)

_______

for my mom

that’s a lot of Haydn, I said to my mom,

when I saw the list of my transmittals in

her hotmail, hm, I wondered, maybe it’s

too much

then I said, but it’s like when we’ve

toured, for instance, our European

art galleries, me propounding on

the paintings, as I am wont, however

incorrigibly, to do, but now, note, you

can tell the difference between your

Monets and your Klimts, however

similar their perspectives

or like your tour guide taking you

recently through Argentina,

highlighting spots, in the space of

a month only, the same amount of

time I’ve spent for the music of

Haydn

pronounced, incidentally, I specified,

like “hidin'” in English, not “maiden”,

just sayin’

I gathered that she’d ‘ve sensed by

now, if she’d been listening, which she

said she had, mornings over her

coffee, what a string quartet is, four

movements, different tempos, fast

at first, a joyful introduction,

followed by a lament, then a spirited

third movement, for countereffect,

then a big fourth movement finish

also, the internal structure of each

movement would’ve been internalized,

a theme, a counter theme, a

recapitulation of both, or either, all of

it, probably unconsciously, which is

how art fundamentally works till you

meticulously deconstruct it

the string quartet is the work of Haydn,

the house that Haydn built, from

peripheral aristocratic entertainment,

like modern day artists sporting their

wares in noisy restaurants, to the

glamour of taking on, in concert halls,

Europe, Brunelleschi did a similar,

sleight-of-hand thing with his dome

in Florence for its oracular Cathedral

remember that the string quartet lives

on as a form, where no longer does

the minuet, for instance, nor the

polonaise, nor even the waltz, not to

mention that concertos, and

symphonies have become now

significantly subservient to movies,

secondary players

watch the instrumentalists here live

out, in Haydn’s Opus 77, no 1, their

appropriately Romantic ardour,

something not at all promoted in

Haydn’s earlier Esterházy phase, to

raise their bow in triumph, as they

do at the end of most movements

is already an indication, not at all

appropriate for the earlier princely

salons, that times have changed

Haydn was a prophet, but also an

elder, with an instrument to connect

the oncoming, and turbulent, century

to the impregnable bond of his

period’s systems, the legitimacy of

the autocratic, clockwork, world,

Classicism, the Age of Reason, the

Enlightenment, for better or for

worse

we are left with its, however ever

ebullient, consequences

R ! chard

February 20, 2017

“First Piano Concerto” – Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

“Concerto“ (1975)

_____

if there’s a piece that defines Classical music

for most people, encapsulates it, even for

those who aren’t especially interested in

Classical music, that piece would be, I think,

Tchaikovsky‘s “First Piano Concerto“

strictly speaking Tchaikovsky isn’t a Classical

composer, but a Romantic one, the Classical

period in music having been transformed

some years earlier into the Romantic period

by none other than Beethoven, 1770 – 1827,

perhaps the most transformative composer

of all time – Tchaikovsky‘s “First Piano Concerto“

was written in the winter of 1874 – 1875, pretty

well at the end of the Romantic Period, which

then ceded to the Impressionists, just to get

our periods right

what the Romantic Period added to the

Classical Era was emotion, sentiment – note

the use of tenuto, for instance, beats being

drawn out, languidly, longingly, for pathos –

what it maintained was the structure, the

trinity of Classical conditions, rhythm, tonality,

and repetition, which is why even the most

uninformed listener will usually be able to

sing along throughout the entire performance,

the blueprint is in our collective blood, in the

DNA of our culture

to remain present a piece must remain

relevant to the promoter, an interpreter must

have reason to play it, substance surely plays

a big part, but technical considerations play

perhaps an even greater role towards a great

work’s longevity, “Chopsticks“, for instance,

is good but it won’t fill a concert hall

unless, of course, it’s with Liberace

the “First Piano Concerto” of Tchaikovsky is

the Everest of compositions, emotionally

complex and technically forbidding, nearly

impossible, it would seem, were it not for

those few who’ve mastered its treacherous

challenges, conquered its nearly indomitable

spirit

Van Cliburn put it on the map for my

generation, with a ticker tape parade in

New York to confirm it

Martha Argerich later on kept the ball rolling

and now Behzod Abduraimov, a mere youth,

born in 1990 in Uzbekistan, Tashkent, delivers

by far the best performance I’ve seen since,

giving it new life for the new millenium

behold, be moved, be dazzled, be bewitched

Richard

April 17, 2015

septet / schleptet – Beethoven / Schikele

“The Swing“ (“Les hasards heureux de l’escarpolette“) 1767

_____

though I’ve spent the last forty years

exploring Beethoven, I still haven’t

heard, much less seen performed

all of his music, unexpected gems

pop up still to prick up even my

weathered ears

but a septet this time, who’d ‘a’

thunk it

the opus 20, not unexpectedly, sounds

like Mozart, formal, musically inventive,

but not prompted by Beethoven’s later

transcendental passions, it was 1800,

he was still showing off his Classical

shoes, spinning andante cantabiles

out of minuets, for no less than Maria

Theresa in this instance, the Empress,

its august dedicatee, not yet having

profoundly outgrown them, the tiara,

the shoes, though you’ll find

expressions of his surpassing majesty

already throughout this masterpiece

six movements, for instance, uppity,

impudent, bold, an impertinence

towards imperial time and its

exigencies, unless it’s worth it, of

course, even in the case of my own

more relaxed schedule

but a precursor to his seven-part

C# minor String Quartet, opus 131,

for its breadth, for its ambition, for

the prefiguring of a monument, a

cultural institution, for its

proclamation of the advent of a

veritable sonic Parthenon

you’ll note a peculiarity, he uses

in the Septet‘s third movement

the same air that served him well

in his 20th piano sonata, opus 49,

no 2, second movement – why not,

it’s his – an earlier composition

despite the later opus number

don’t ask

opus 49, no 2 has only two

movements, incidentally, like his

earlier opus 5, no 1, or his later

incandescent no 111, to shed light

on the chronology of his musical

evolution, his eventual historical

apotheosis

find the movement with variations

in the Septet, your body will tell

you, much like it does slow tempi

from fast ones, you merely listen

with your senses, not just your

ears, your unconsciousness, while,

distractedly, you’re, say, washing

dishes, you’ll say, hey, I’ve just

heard this before, but different,

only this minute

hence the term variation

compare this Schleptet in Eb major,

from Peter Schikele for fun, from

the year 2000, a spoof on Beethoven’s

Septet in the identical key the

better to roast him, but in five

movements this one, in the Classical

style, but where the mood is neither

Classical, nor even Romantic, it’s

ironic, satirical, wry, even cynical,

note the slapstick tempo markings

I. Molto Larghissimo – Allegro Boffo

II. Menuetto con brio ma senza Trio

III. Adagio Saccharino

IV. Yehudi Menuetto

V. Presto Hey Nonny Nonnio

the voice, for better or worse, of our

time

Richard

March 21, 2014

Beethoven – piano sonata no 7, in D major, opus 10, no 3

“Euterpe – Apollo and the Muses“ (2008 – 9)

________

if the piano sonata no 4 of Beethoven,

in E flat, opus 7, was academic, an

exercise, a display of technical

dexterity and some, admittedly,

even mighty, compositional verve,

it lacked, in my estimation, a centre,

a convincing motivating factor, a muse,

though ever ardent, ever entertaining,

it is ultimately arid, I think, trite, I’m

not, one is not, keen on returning to it

but in the piano sonata no 7, in D major,

opus 10, no 3, Beethoven hits, I submit,

his stride, this sonata is enchanting

note the similarities of structure

between the two, the order of the

movements with identical, essentially,

tempo patterns, notably the middle

slow movement, in the first a largo,

con gran expressione, slow with

great expression, in the latter, a

largo e mesta, slow with sadness,

where Beethoven plumbs, evidently,

the limits of pacing, the time lapse

between two notes, the capacity for

silence of this new instrument, the

pianoforte, of which he’ll look into

also, and even vigorously, its

capacity for volume, the crashing

introduction to his celebrated 8th,

for instance, to establish the

instrument’s new perimeters

you’ll note you can listen to the later

largo, the opus 10, no 3, forever, you

can get lost in its aural world, I can’t

think of anywhere else right now a

more profound largo

the other movements are dazzling

in their thrilling prestidigitation, all

organically sound, and, crucially,

motivationally centred, I think, this

is indeed music, magisterial music,

Beethoven’s not just kidding

anymore, he’s hitched onto his

proper inspirational deity, his own

private Euterpe, music’s muse, and

we’re in for something, from here

on, of a ride

note the cool riff closing off the last

movement, Beethoven in the guise

of Gene Kelly stepping in for a

breezy good-bye, prefiguring, of

course, XXth-Century music, and

the serendipitous extrapolations

of jazz

Richard

psst: incidentally, the headings, largo,

con gran expressione, largo e

mesta, are entirely Romantic

musical notions, notations,

Classical composers would’ve

been too sedate, formal, courtly,

for such flagrant sentiment

June 18, 2013

Liszt – piano concerto no 2 in A major

since discovering Tamás Érdi, feral hands,

uncommonly hirsute, but uncovering the

soul of a poet, an angel in wolf’s clothing,

a satyr, without a flute but, at the piano,

I’ve been hooked, combined with Liszt he

is again irresistible, not to mention totally

transcendental

you’ll find Liszt quite a bit like Beethoven,

but more bombastic than philosophical,

style trumps substance, Liszt was a

show-off, a pianistic Paganini

stylistic flourishes abound in the hands

of a deft, however uninformed might he

or she be, technical wizard, it doesn’t

take an Einstein, in other words, to be

a Puccini

and Liszt is a Puccini, who delivers

likewise, and for the very ages

note the same intensity as Beethoven

in Liszt, much of the same musical

idiosyncrasies, but with more dramatic,

late Romantic, alterations of tempo, he’ll

milk a phrase before returning to a more

Classical, which is to say, less elastic

beat

his extemporisations are also less

ruminative, more serendipitously

motivated, like jazz, Liszt wants

primarily to dazzle, kick around,

not instruct

and he does, masterfully, just that

here’s Alfred Brendel doing an alternate,

wholly incandescent version I couldn’t

at all leave out

here’s Julie Andrews giving her take on

the history of jazz

Richard

April 26, 2013

Beethoven Strinq Quartet no 14, opus 131

if Beethoven had written merely one transcendental

work we would still have been beholden, but that he

wrote neither two, nor three, but several immutable

pieces is extraordinary, super-, apparently, human,

though, of course, manifestly not, unless you want

to bring Jesus into the picture as such a dual being,

then we’ll talk, but Beethoven is a staunchly secular

voice, devoid of the spiritual considerations of a

Bach, for instance, Beethoven speaks for humanity,

its longings, consternations, aspirations, its essence,

no longer the discredited primacy of the Cross and

Its imperial derivatives, Human Rights have trumped

God

what Beethoven maintains however is the reverence,

his later pieces – you’ve heard the “Hammerklavier“,

already, the 32nd piano sonata – are manifestly

spiritual experiences, as opposed to religious

the 14th String Quartet will do the same

if the “Hammerklavier“ is akin to Moses delivering

his peremptory tablets, the 14th String Quartet is

the Sermon on the Mount, in the history of music

they have so great an impact

briefly, as briefly as I can, I’ll say a few introductory

words, then let your soul and the music do the rest,

see what happens to your karma

there are seven movements in the 14th, uninterrupted,

no pauses between the movements, though each is

easily identifiable, tempo therefore becomes incidental

instead of Classically ordered, the first movement, for

instance, is an adagio, a Classically improbable spot

the sections therefore play much as chapters in a

novel, advancing according to the logic and emotions

of the moment, always, as in all of Beethoven, moving

inexorably forward despite the intricacies of the, not at

all predictable, plot, as had been the case in the more

regimented Classical model, Beethoven takes you,

instead of around the corner, into the clouds, into a

spiritualized heaven, a place of profound existential

introspection

try listening to the 14th String Quartet attentively

without thinking about your soul, its existence,

its mission, in the very face of its ineradicable,

and fateful, actuality, the human conundrum,

Beethoven lets us know we’re not alone

some mountaintop Sermon indeed, watch what

happens to your sensibility, your very sacred

self, or maybe I should say, listen

may your path be decked meanwhile with laurels,

and your days be blessed with grace, be it ever

so merely, maybe, human

who knows

sincerely

Richard

psst: if you’ll allow me to pursue my series of

similarities you’ll imagine piano sonata

no 32 as Beethoven’s “Last Supper”,

this one in particular five luminous stars