how to listen to music if you don’t know your Beethoven from your Bach, XV – what’s a rhapsody

“Rhapsody of Steel“ (1959)

________

so what’s a rhapsody

“Rhapsody of Steel“ (1959)

________

so what’s a rhapsody

______________

if I’m including Tchaikovsky’s Third,

and last, Piano Concerto in my survey,

it’s not because of its excellence, it is,

indeed, severely flawed, but because

I am a completist – if I’m visiting the

Cologne Cathedral, ergo, for instance,

I’ll make my way to the very top,

however treacherous might be the

stairs, the gargoyles being worth it,

not to mention the view

first of all, it’s incomplete, Tchaikovsky

died before finishing it, you can’t blame

him for that, though he was, curiously,

complicit in his own demise, but I don’t

believe this composition and his death

are that intimately interrelated

it has only one movement, but has

nevertheless been termed a concerto

on the, debatably unsound, strength

of its intention

briefly, and this is my opinion, the

movement has no lyrical moment,

no melting melody to float you out

of the recital hall as you exit,

nothing to hum, nor to whistle as

you wistfully wend your way back

home, nothing to remember but

flash, braggadocio, bombast,

expert fingers strutting their

dazzling, even, stuff, style over

substance, I venture, won’t be

enough to whisk you into the

following centuries

Chopin, the other towering Romantic

figure standing between the spiritual

bookends of Beethoven and Brahms,

wrote two piano concertos, of which

his Second suffers from, essentially,

not being his First, however mighty

his Second here, for instance,

proves to be in this utterly convincing

performance, watch, wow

Beethoven, in other words, wrote the

book, two works, Tchaikovsky’s First

and Chopin’s First, tower above his

in the public imagination during the

ensuing High Romantic Period, after

which Brahms closes the door on the

era with his two powerful masterpieces

for piano and orchestra

of which more later

there are other piano concertos

along the way, but Beethoven’s

five, Tchaikovsky’s and Chopin’s

one each, and Brahms two are

the basics – but let me add, upon

further consideration, and for a

a perfect ten options, Liszt, his

own, of two, First Piano Concerto –

what you need to consider yourself

comfortably aware of the essentials

of music in the 19th Century, the

culture’s predominant voice then,

until art, painting, took over as the

Zeitgeist‘s most expressive medium

with Impressionism

of which more later

R ! chard

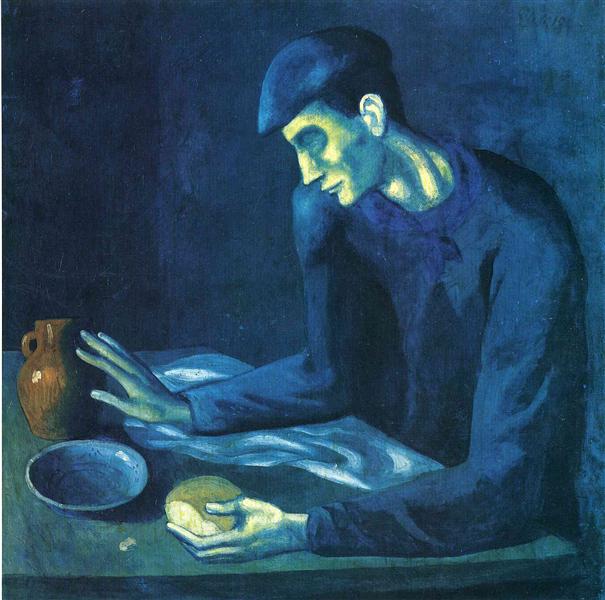

“Blind Man’s Portion“ (1903)

________

though you’ll have to actively listen

to Christopher King rather than

merely hear him here, as you might

have been doing with many of my

suggested musical pieces, should

you be at all interested in the history

of music, he is fascinating, dates his

investigations back millennia to very

Epirus, Ancient, nearly primordial,

Greece, to mirologia there, ancient

funerary chants

some have survived, and have been

recorded for posterity, one, in 1926,

by a Greek exile fled to New York City,

Alexis Zoumbas, a year later, however

improbably, by an American, a blind

man, his own story inspirational, akin

to that of Epictetus, one of the two

iconic Stoic philosophers, the other,

incidentally, an emperor, though the

blind man here, Willie Johnson, was

never himself a slave, but only, by a

historical whisker, the emancipations

of the American Civil War

Christopher King‘s comparison

of an Epirotic miralogi with an

American one brings up, for me,

the difference between Mozart

and Beethoven, notice how the

Willie Johnson version is more

rhythmic, the cadence is much

more pronounced than in the

Greek one, Johnson would’ve

got that from the musical

traditions Europeans had

brought over from their native

continent, probably also from

Africa, Africans

Beethoven would’ve been

surrounded, meanwhile, by Roma,

perhaps called gypsies then, their

music ever resonant in his culture,

not to mention later Liszt‘s, and

the Johann Strausses’ even, for

that matter, Paganini also seems

to have been imbued with it, it

having come up from Epirus

through, notably, Hungary – not

to mention, later still, that music’s

influence, and I’ll stop there, on

late 19th-Century Brahms

Christopher King, incidentally,

sounds a lot like someone you

already know, I think, from his

eschewing – Gesundheit – cell

phones, for instance, to his

enduring preoccupation with

death, not to mention his

endearing modesty, indeed

his humility, his easy

self-deprecation, despite his,

dare I say, incontestable, and

delightful, erudition

makes one wonder why that

other hasn’t become also

famous yet

what do you think

R ! chard

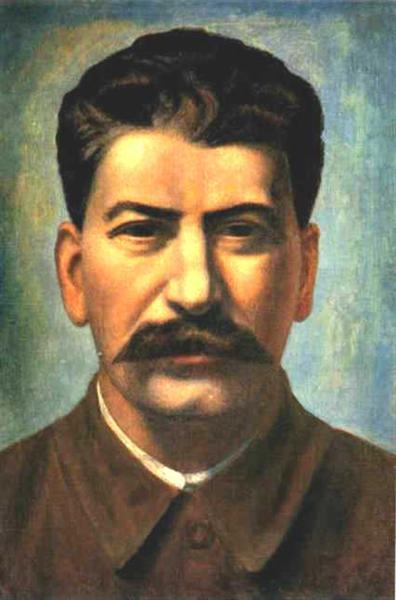

“Portrait of Joseph Stalin (Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili)“ (1936)

_________

if you’ve been waiting for a Shostakovich

to write home about among his early

symphonies, here’s the one, his

Symphony no 4 in C minor, opus 43 will

knock your socks off from its very

opening gambit, have a seat, settle in,

and get ready for an explosive hour

the Fourth was written in 1936, some

years after the death of Lenin, and the

instalment of Stalin as the supreme,

and ruthless, authority, after several

years throughout the Twenties of

maneuvering himself, cold-bloodedly,

into that position

from Stalin, “Death is the solution to

all problems. No man – no problem.“

fearing retribution after Stalin had

criticized his recent opera, “Lady

Macbeth of Mtsensk“, Shostakovich

cancelled the first performance of

this new work, due to take place in

December, ’36, others had already

suffered internal exile or execution

who had displeased the tyrant, a

prelude to the infamous Great Terror

the Symphony was eventually played

in 1961, 25 years later, conducted by

no less than Kirill Kondrashin, who’d

partnered Van Cliburn a few years

earlier in Cliburn’s conquest of Russia,

but along with this time however the

long-lived Leningrad Philharmonic

Orchestra

to a friend, I said, this is the biggest

thing since verily Beethoven, no one

has so blown me away symphonically

since then

he looked forward, he replied, to

hearing it

the Fourth Symphony has three distinct

movements, to fit thus appropriately the

definition of symphony, though the first

and third have more than one section,

something Shostakovich would have

learned from already Beethoven, it gives

the opportunity of experiencing a variety

of emotions within one uninterrupted

context, add several movements and

you have a poignant, peripatetic musical

journey, more intricate, psychologically

complex, than many other even eminent

composers, Schubert, Chopin,

Mendelssohn, even Brahms, for instance

it’s helpful to think of film scores, and

their multiple narrative incidents,

brimming with impassioned moments,

however disparate, Shostakovich had

already written several of them

let me point out that Shostakovich’s

rhythms are entirely Classical, even

folkloric in their essential aspects,

everywhere sounds like a march,

proud and bombastic, if not a

veritable dance, peasants carousing,

courtiers waltzing, and repetition is

sufficiently present to not not

recognize the essential music

according to our most elementary

preconceptions

but the dissonances clash, as though

somewhere the tune, despite its rigid

rhythms, falls apart in execution, as

though the participants had, I think,

broken limbs, despite the indomitable

Russian spirit

this is what Shostakovich is all about,

you’ll hear him as we move along

objecting, however surreptitiously,

cautiously, to the Soviet system, like

Pasternak, like Solzhenitsyn, without

ever, like them, leaving his country

despite its manifest oppression, and

despite the lure of Western accolades,

Nobel prizes, for instance, it was their

home

and there is so much more to tell, but

first of all, listen

R ! chard

__________

for Barbara, who died recently,

she would’ve loved this

Shostakovich was just nineteen when

his Symphony No.1, opus 10 was

first performed – it had been his

graduation piece the previous year

from the Petrograd Conservatory –

by, then, which is to say 1926, the

Leningrad Philharmonic, renamed the

Saint Petersburg after the fall of the

U.S.S.R., the name it had held before

the Bolshevik Revolution, the oldest

philharmonic orchestra, therefore,

incidentally, in our Russia, going

back to 1882

the work was a complete success, not

surprisingly, if you’ll consider its scope,

its power, and its novel musical

interpolations, I mean a piano as an

integral orchestral instrument rather

than as a distinct, however interrelated,

component, a pas de 40 instead of a

pas de deux, something I can’t remember

anywhere else having seen for piano

not to mention the drum roll between

the last two movements, drums making

a splash in an orchestral setting, who’d

‘a’ thunk it, though Richard Strauss had

done just that in his extraordinary

“Burleske” several decades earlier,

another youthful work, Strauss only 21

but meanwhile back in Russia, before

I too seriously digress, Shostakovich

was immediately compared to another

earlier young prodigy there, Alexander

Glazunov, who’d himself put out his

own First Symphony, the “Slavonic“,

at age 16, introducing, incidentally, his

own instrumental novelty then, an oboe

obbligato, which by very definition is

lovely

Glazunov also mentored, by the way,

Shostakovich at the Petrograd, proved

to be instrumental indeed in his

progress

it’s interesting to put these last two

together, to compare, the Glazunov, 1881,

follows the traditional Romantic

imperatives, tempo, tonality and

repetition, but with more bombast, to my

mind, than its European counterparts,

its fields are the Russian steppes with

troikas, horse-drawn carriages, flying

across vast unhampered vistas of the

Russian snow-covered, therefore

pristine, tundra, to whet the unbridled

Russian spirit, the Europeans, Brahms,

Mendelssohn, Mahler, conversely,

are confined to the hunt, however ever

glorious, but with shrubs, copses,

thickets, if not veritable forests, to blur

the sonic arena, inspire dreams,

consequently, less far-reaching than

those of Johnny Appleseed even, of

the North American Prairies poets,

their own far-flung, boundless

imaginations, inspiration, you can

hear it all, blatantly, in the resonance

of the horns

you’ll note the movements follow

essentially the same rhythmic order

in either symphony, the first two fast

enough, then a third that’s somewhat

slower, a variation from the strictly

Classical order of fast, slow, fast, then

a last, eclectic, movement

but Shostakovich is more atonal,

melodically divergent, an eccentricity

he’ll later polish to a degree of

politically subversive brilliance

for not submitting, however, to the rule

of repetition, which is manifest, though,

in Glazunov, Shostakovich, I find, leaves

us trying to find our bearings as his music

rolls along, kind of like in biographical

movies, when you start looking at your

watch to determine how many life

incidents remain in this particular,

however significant, existential drama

as spectacle – and it must be noted that

symphonic displays were at the time

indeed spectacles – there was no

phonographic, photographic

equipment to transmit such

experiences, the symphony itself was

the show, it had, right there, itself, to

wow the audience

in all of these cases, all of them did

Shostakovich, however, of all of them

remained eventually potently

pertinent, powerfully paramount,

watch

R ! chard