Richibi’s Weblog

Category: walking in beauty

October 4, 2020

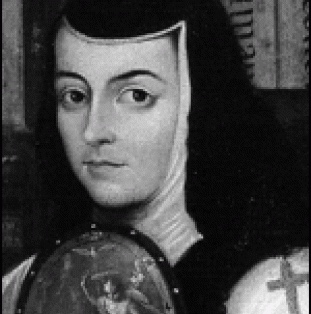

“Love Opened a Mortal Wound” – Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1651–1695)

___________

in both style and substance, the

following poem reminds me of

Emily Dickinson‘s wonderful stuff

the poet, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz,

1651–1695, was the illegitimate

daughter of a Spanish father and

a Creole mother, who chose to

follow her many intellectual pursuits

and become a nun rather than submit

to the rigours of love and a secular life

R ! chard

_________________

Love Opened a Mortal Wound

Love opened a mortal wound.

In agony, I worked the blade

to make it deeper. Please,

I begged, let death come quick.

Wild, distracted, sick,

I counted, counted

all the ways love hurt me.

One life, I thought—a thousand deaths.

Blow after blow, my heart

couldn’t survive this beating.

Then—how can I explain it?

I came to my senses. I said,

Why do I suffer? What lover

ever had so much pleasure?

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

(translated by Joan Larkin

and Jaime Manrique)

Con el Dolor de la Mortal Herida

Con el dolor de la mortal herida,

de un agravio de amor me lamentaba;

y por ver si la muerte se llegaba,

procuraba que fuese más crecida.

Toda en el mal el alma divertida,

pena por pena su dolor sumaba,

y en cada circunstancia ponderaba

que sobrarban mil muertes a una vida.

Y cuando, al golpe de uno y otro tiro,

rendido el corazón daba penoso

señas de dar el último suspiro,

no sé con qué destino prodigioso

volví en mi acuerdo y dije:—¿Qué me admiro?

¿Quién en amor ha sido más dichoso?

September 22, 2020

Serenade after Plato’s “Symposium” – Leonard Bernstein

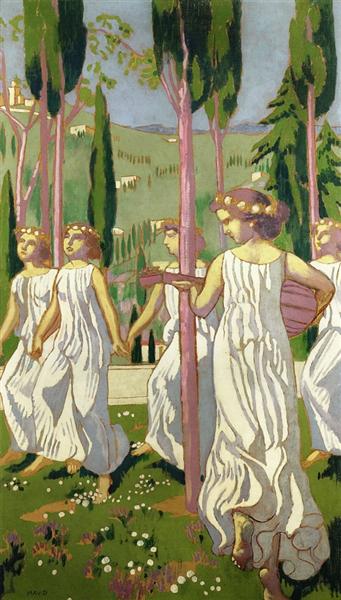

“Plato’s Symposium“

Anselm Feuerbach

__________

imagine my surprise when having put

on a concert I’d recently taped from

television and, not having checked

out the program, apart from having

noted the featured violinist, someone

I, however peripherally, knew, then

heading out to the kitchen to do

some kitchen things, chop vegetables,

stir a pot, watch water, maybe, come

to a boil, a piece came up with which

I wasn’t familiar, thought maybe it

might be Shostakovich for its atonality,

though with, here again, his signature

decipherable melodies, ever, and

characteristically, maimed, twisted,

contorted, for, too, its Eastern

European rhythms, its apparent

Jewish folklore, touches of Fiddler

on the Roof, I thought, hints of

Schindler’s List, maybe, when the

work turned out to be, however

improbably, by Leonard Bernstein,

most famous, rather, for his Broadway

shows, West Side Story, for instance,

but especially as a conductor

his Serenade for violin, string orchestra,

harp and percussion, known also as

Serenade after Plato’s “Symposium”,

was written, in 1954, in commemoration

of a couple of personal friends, husband

and wife, after their demises

Plato‘s Symposium is one of his several

dialogues, a clutch of noteworthy

Athenians meet socially after an earlier,

more crowded, revel, a kind of debriefing,

and decide to each give his definition of

love, the work remains one of the great

disquisitions on the subject, not tackled

much since, surprisingly, in the history

of philosophy

there are seven people in attendance,

though Alcibiades, yes, the Alcibiades,

orator and statesman, stumbles into

the gathering, late and last

Bernstein has a voice for each

participant, though in five rather than

seven movements, two couples, the

first and the last, have no break

between their conjoined movements

I. Phaedrus: Pausanias – lento and allegro

II. Aristophanes – allegretto

III. Eryximachus, the doctor – presto

IV. Agathon – adagio

V. Socrates: Alcibiades – molto tenuto and allegro molto vivace

in the Symposium, Eryximachus speaks

before Aristophanes, yes, the Aristophanes,

the playwright, cause the bard has the

hiccoughs, and the doctor, Eryximachus,

agrees to go first, if out of the agreed upon

order, an order that Bernstein chooses not

to follow, for reasons to do with tempo, I

suspect, otherwise the progression is as

in Plato

Eryximachus, interestingly, advises

Aristophanes to make himself sneeze,

a cure apparently for hiccoughs, in

order to be ready for his turn, which

he does, and indeed manages

Agathon was a poet, his adagio here

is accordingly gorgeous, melting,

completely appropriate for a writer

of verse, and entirely, incidentally,

worth the price of admission

Socrates‘ molto tenuto, even and

tempered, measured, is, likewise,

totally apt for a philosopher

enjoy

R ! chard

September 17, 2020

Preludes and Fugues, Op.87 – Shostakovich