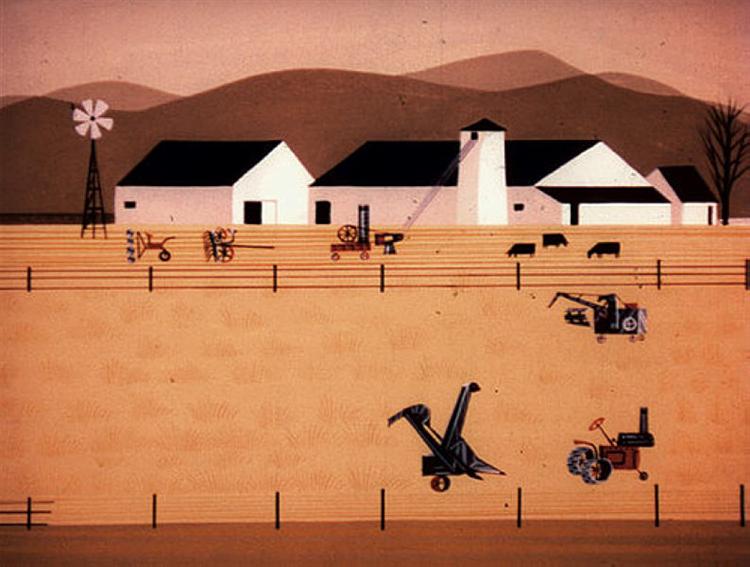

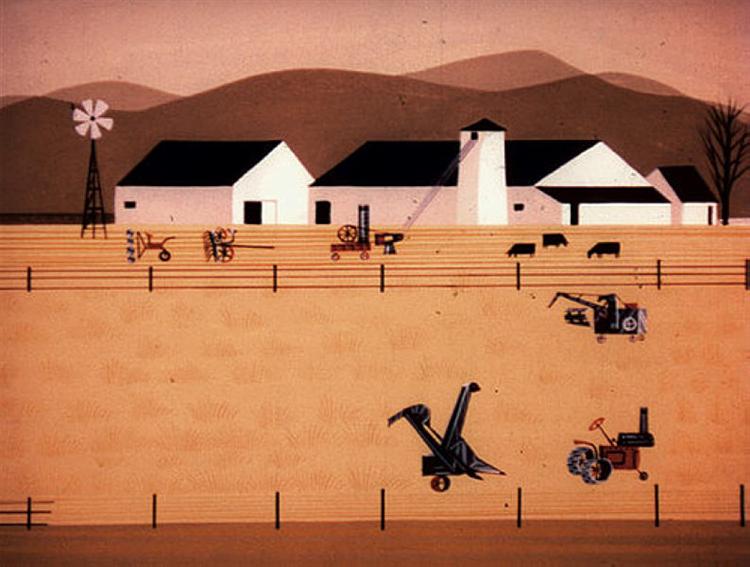

“Rhapsody of Steel“ (1959)

Eyvind Earle

________

so what’s a rhapsody

if you’ve been following at all my

heard by now several rhapsodies

at first, I suggested that the rhapsody

was an evolution from the fantasia,

a piece of music in one movement

that allowed for any internal

construction, but that, after the

Classical Period, became imbued

with Romanticism, passion became

a condition of music, mere technical

ability was no longer enough

note that the audience was different,

rather than nobles who commissioned

artists to decorate their salons, the

burgeoning Middle Class was hungry

for them to entertain, performers were

becoming the main attraction, not just

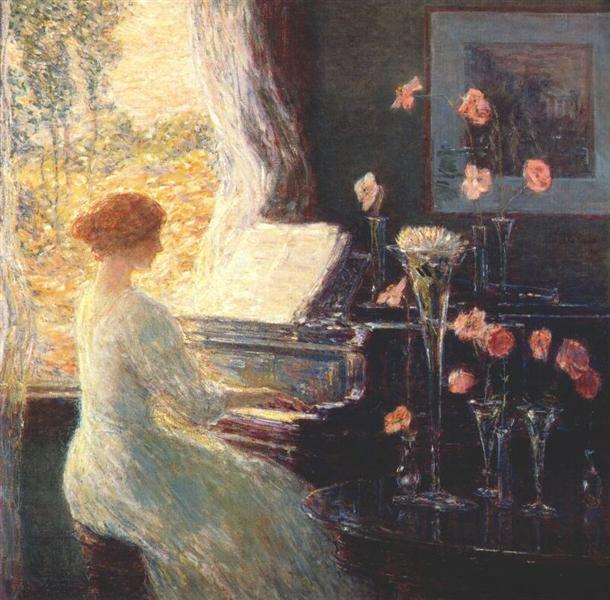

the background, see, for instance,

Beethoven

but not only did rhapsodies spread

from just one player to an entire

orchestra – see Brahms, then

see Gershwin – but its essential

structure, one movement, was

challenged, see Ravel here, or

are both composed of distinct

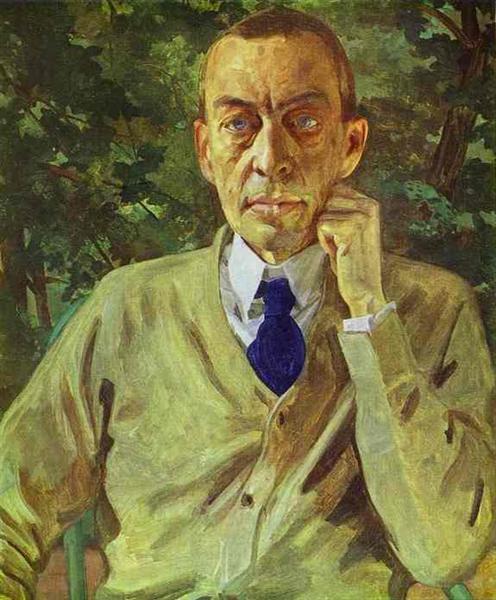

movements, Rachmaninov even

further refining his movements

into variations, for years, I

Variations

all this to say that a rhapsody is

turning out to be not identified

by its structure, its technical

parts, but rather by its intention,

a rhapsody is in the eye of its

composer, like a nocturne, or

a ballade

I’d thought that rhapsodies had

been relegated to the Romantic

Era, with the occasional later

tribute

who, I wondered, could be

writing rhapsodies anymore

but here’s something, however

unexpectedly, you’ll be familiar

with, from 1975, Queen’s Bohemian

Rhapsody, in several movements

– intro, ballad, opera, hard rock,

outro – and including in all of them,

note, voice

all of which speaks of tradition

being a lot closer than one would

think, ancestral, residual, but

defining, traces, like genes,

however updated, however

posthumously interpreted,

pervade, infiltrate, pursue,

inexorably

rhapsodies are in our DNA, it

would appear, for better or for

worse, ever

here’s to them

R ! chard

.jpg!Large.jpg)