String Quartet no 2 in D major – Alexander Borodin

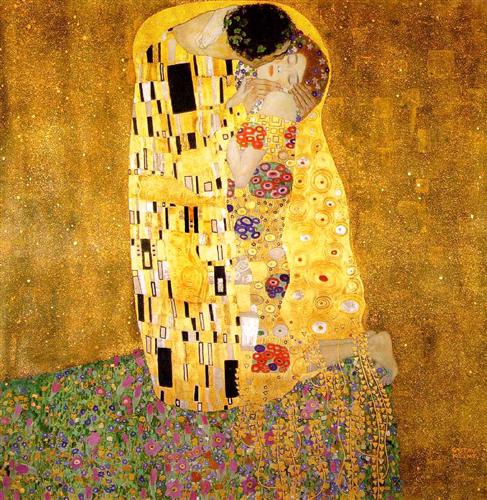

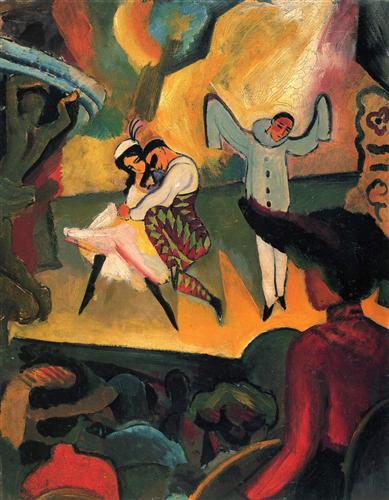

“Russian Music“ (1881)

_______

Alexander Borodin’s ravishing String

Quartet no 2 in D major, from 1881,

was written only a few years after

Smetana’s 1876 “From My Life“, and

sounds surprisingly similar, the same

number of movements all in the same

order, fast, a dance step, polka or

waltz, then slow, then fast

their second movements are notably

united by their common use of long

bowing of paired notes from the

violins, to establish, irresistibly,

the rhythm of their individual dances

their eccentric, even strident notes,

stretching towards atonality but

remaining this side of the divide,

thus surprisingly welcome, even

captivating

the change of tempo right in the

middle of every movement to

separate and sharpen contrast

between the exposition and the

development, then the whole

thing all over again, all quirks

of the evolution of the

nevertheless stalwart string

quartet structure, as unassailable,

it would appear, as that of the,

also inveterate, sonnet

I could go on

the difference is in the intention,

the appropriation of the Viennese

model to express more culturally

expanded varietals of the original

mode, in these two cases, Czech

and Russian, it’s all in each their

homegrown cadence

and that’s how music speaks if

you lend an ear

think of the European Pinot Noir,

for instance, taking root in other,

foreign soil not being necessarily

any longer inferior, sometimes

even superior, downright even

celebrated, you’ll get, essentially,

the big picture

Alexander Borodin’s ravishing

String Quartet no 2 in D major,

note, is such a prize, an utterly

intoxicating wine you wouldn’t

want to eschew, miss

Gesundheit

Richard