“Metamorphoses” – Ovid, 102

you think I’ve got a big ego, I asked

a friend who’d just told me I had one,

not confrontationally but as a matter

of fact, I wasn’t offended, just curious,

I think I’m so humble, I answered,

usually, so deferential

“John Philip Kemble as Hamlet“ (1801)

___________

if I’m to compare Beethoven’s 32nd

Piano Sonata, his opus 111, with

anything else you might be familiar

with, it would be Shakespeare’s

epochal contemplation, “To be, or

not to be“, both are, first, and

briefly, soliloquies, one performer

alone is on stage, both are

implicitly meditations, that will

augur, inspire, note, a new age

let me propound, for a moment, on

the Shakespeare, an introspective

piece set on resolving an existential

dilemma, To be, or not to be, that is

the question, it is pungent, forceful,

arresting, if only even rhythmically,

so much so that many still

pronounce the first line of that

trenchant aria with verily stentorian

conviction, without realizing that the

several concluding movements are

abysmally dire, indeed they

investigate, with improbably literate

fervour, a life and death situation

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles

And by opposing end them

should one, after contemplation,

bear the onslaught of life’s most

unacceptable tribulations, or,

most efficiently, cut all of it off

… To die – he says – to sleep,

No more; and by a sleep to say we end

The heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to: ’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished

I’ve often been there

... To die, to sleep;

To sleep, perchance to dream – ay, there’s the rub:

the rub, which is to say, the problem,

what’s up once you’ve done yourself

in

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause

indeed, there’s the respect, the angle,

the conundrum one must consider

that makes calamity of so long life

one ‘s stuck between the devil and the

deep blue sea

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

Th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely

the demeaning disrespect a proud man ‘s

made to suffer

The pangs of dispriz’d love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of the unworthy takes

which is to say, life’s multifarious, and

beleaguering struggles

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin?

quietus, silence, extermination

bodkin, a knife

… Who would fardels bear,

fardels, hardships

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscover’d country, from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others we know not of?

we keep on grunting, in fear that

what comes after could be worse

a man considering his own demise,

his quietus, at the time of Shakespeare

would’ve been, only a generation earlier,

an heretic, one deserving of unforgiving,

and gruesome, censure, Hamlet was,

not incidentally, however, a prince, a

role model, though evidently controversial

but the Reformation had occurred,

a loosening of categorical strictures

in France, Descartes had, in his quest

for the true God, concluded, Cogito,

ergo sum, I think, therefore I am,

eclipsing the Catholic God as the

final arbiter, personal metaphysical

options were up for grabs, out in

the open, though yet not entirely

secular

which would happen, out loud, in

the Age of Reason, when God, as

we knew Him, lost His, by now

scattered, authority, among

Lutherans, for instance, Calvinists,

Anglicans, and a proliferation of

sprouting others, not to mention,

still, the stalwart, ever, Roman

Catholics

the Romantic Period needed a new

ethic, a personal evaluation of one’s

metaphysical position, Beethoven,

in a word, or in his 32nd Piano

Sonata rather, delivers, a piece no

less intense than Shakespeare’s

profound interrogation

briefly, there are two movements

here, merely, which demand your

attention, it isn’t music that one

listens to with just one ear, this

is Jesus on the Mount of Olives,

Gethsemane, not much different

from Shakespeare’s existential

soliloquy

war, peace, rebellion, resignation,

black, white, fast, slow, explosive,

extended, man, woman, yin,

indeed, yang, short, long,

irascible, submissive, all

paradoxical dichotomies, all

eventually, manifestly,

transcendent, all a subjugation,

a private prayer, eventually,

however fraught, however

nevertheless archetypal,

two movements that still

haven’t exhausted their

philosophical potential for

being assuaging, inspirational

R ! chard

me, May 24, 2016

__________

I save all the New Yorker poems

to read after I’ve been through

everything else in the issue,

like dessert after a meal, icing

on the cake, sometimes too

heavy, sometimes too light,

sometimes too rich, sometimes

just right

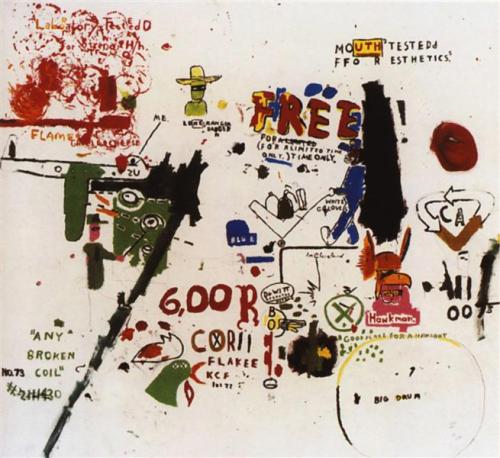

today, I found my favourite poem,

period, this year, stepped right

into its shoes, like old slippers,

the only difference being my

walls are painted a variety of

contrasting colours, studded

with memorabilia, treasured

artefacts, see above

also, no one’s translating my

poems, though even our metre

is the same, try it, sing us out

loud, you’ll dance

R ! chard

_____________

Every time Gulliver travels

into another chapter of “Gulliver’s Travels”

I marvel at how well travelled he is

despite his incurable gullibility.

I don’t enjoy travelling anymore

because, for instance,

I still don’t know the difference

between a “bloke” and a “chap.”

And I’m embarrassed

whenever I have to hold out a palm

of loose coins to a cashier

as if I were feeding a pigeon in a park.

Like Proust, I see only trouble

in store if I leave my room,

which is not lined with cork,

only sheets of wallpaper

featuring orange flowers

and little green vines.

Of course, anytime I want

I can travel in my imagination

but only as far as Toronto,

where some graduate students

with goatees and snoods

are translating my poems into Canadian.

__________

psst: I said just recently to a poet

acquaintance that what poetry

needed in the 21st Century is

humour, the only art form not

catching up with the rest,

otherwise it’ll die of, indeed

succumb to, its own

lugubriousness

thank you again, Billy Collins

‘El Jaleo‘ (1882)

_________

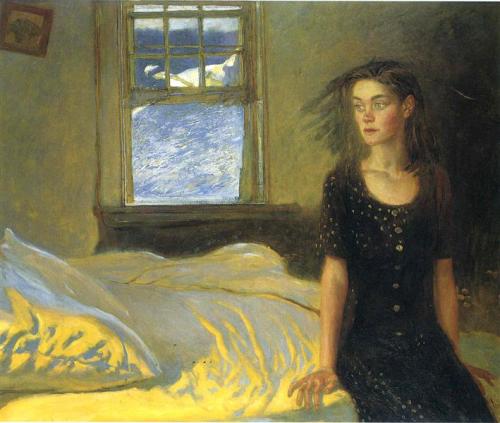

After a history lesson, crash course in Buenos Aires

a hundred years before our time, we begin

at last. You gently place my arm over yours, my hand

on your shoulder, our bodies distant enough

to have an invisible body between us – this is open embrace,

you explain, abrazo abierto. We dare not dance in abrazo cerrado,

where our chests would nearly touch – I’m not single-

minded enough about learning these moves to unlock

what I fear might spill out, should I let myself fall

into your hazelnut voice – so rich and deep I might never

emerge from it. You teach me the new skill of following,

though your lead feels less like control and more

like stewardship, carving swans of negative space

that stretch their graceful necks along the diagonals

of our bodies. We’re in a conversation of pauses

and advances. I step too soon, but you are eminently patient,

your large hand over mine, poised mid-air, a paper crane

mid-flight. As you shift your weight from side to side,

I wait, trying to sense which way we are going,

and for a moment, I have the chance to look at you not

looking at me, your calm grey eyes fixed above my head.

On the small of my back, your warm hand –

a breathing orchid, cupped flame.

____________

for, especially, Tonyia

the clash of cultures is exposed to the light

here as a tango dancer teaches an English-

speaking novice how to dance

there is no evident metre in the verse, the

poem is in prose, contained within terse,

two-lined stanzas which act as constraints

on the forward flow, however ever fluidly

continuous, like tenutos in music, where

the note is held, dramatically, before a

return to the original rhythm

but slowly this prose develops its own

irresistible rhythms, an abandonment

to the metre of the whole, a languid

surrender to the pulse and propulsion

of the dance, and becomes, despite

its, ahem, flat feet, a poem

the very vocalic construction of

Romantic languages, abrazo abierto,

for instance, or abrazo cerrado,

propelled by vowels for their forward

motion, in imitation of the heartbeat,

preclude in natives unfamiliarity with

cadence, the tango is already in their

blood, the teacher here ineluctably

lives, breathes, hir ethnic identity

Anglo-Saxons and Teutons excel,

rather, at political science and

philosophy, more sober, cerebral

preoccupations, suppressing

gutturally in their glut of gurgled

consonants, the more carnal

allure or, from a primmer

perspective, temptations, of the

senses

which Romantic poets, incidentally,

pointedly sought out in the seductive

rhythms of the Mediterranean, much

as this very student succumbs to the

‘breathing orchid’, the ‘cupped flame‘

of this tantalizing tango

Richard

__________

happy poems about February are not

easy to find, nor are poems by any

poet written for each month of the

year

but here are Algernon Charles

Swinburne‘s “January” and “February”

from his “A Year’s Carols“

January

Hail, January, that bearest here

On snowbright breasts the babe-faced year

That weeps and trembles to be born.

Hail, maid and mother, strong and bright,

Hooded and cloaked and shod with white,

Whose eyes are stars that match the morn.

Thy forehead braves the storm’s bent bow,

Thy feet enkindle stars of snow.

February

Wan February with weeping cheer,

Whose cold hand guides the youngling year

Down misty roads of mire and rime,

Before thy pale and fitful face

The shrill wind shifts the clouds apace

Through skies the morning scarce may climb.

Thine eyes are thick with heavy tears,

But lit with hopes that light the year’s.

March’ll have to wait

most of us have never even heard of

Swinburne, I actually thought he was

German, he’s not, he was English,

and decadent, apparently, like his

compatriots then, Dante Gabriel

Rossetti and Oscar Wilde, who

thought Swinburne, however, was

a sham

though he never received a Nobel prize,

he was nominated for one in literature

each year from 1903 to 1907, then

again in 1909

to Swinburne

Richard