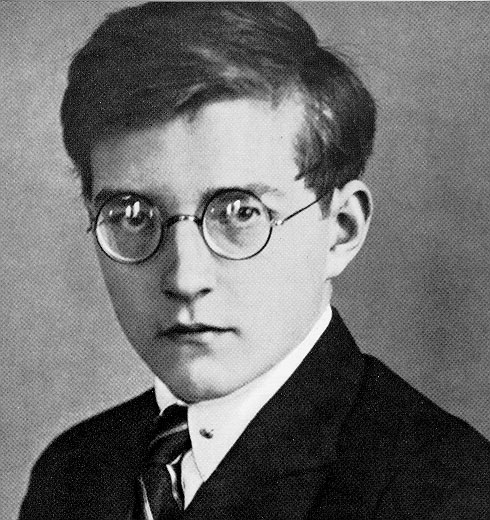

Dmitri Shostakovich – Symphony no. 1, opus 10, continued

__________

for Barbara, who died recently,

she would’ve loved this

Shostakovich was just nineteen when

his Symphony No.1, opus 10 was

first performed – it had been his

graduation piece the previous year

from the Petrograd Conservatory –

by, then, which is to say 1926, the

Leningrad Philharmonic, renamed the

Saint Petersburg after the fall of the

U.S.S.R., the name it had held before

the Bolshevik Revolution, the oldest

philharmonic orchestra, therefore,

incidentally, in our Russia, going

back to 1882

the work was a complete success, not

surprisingly, if you’ll consider its scope,

its power, and its novel musical

interpolations, I mean a piano as an

integral orchestral instrument rather

than as a distinct, however interrelated,

component, a pas de 40 instead of a

pas de deux, something I can’t remember

anywhere else having seen for piano

not to mention the drum roll between

the last two movements, drums making

a splash in an orchestral setting, who’d

‘a’ thunk it, though Richard Strauss had

done just that in his extraordinary

“Burleske” several decades earlier,

another youthful work, Strauss only 21

but meanwhile back in Russia, before

I too seriously digress, Shostakovich

was immediately compared to another

earlier young prodigy there, Alexander

Glazunov, who’d himself put out his

own First Symphony, the “Slavonic“,

at age 16, introducing, incidentally, his

own instrumental novelty then, an oboe

obbligato, which by very definition is

lovely

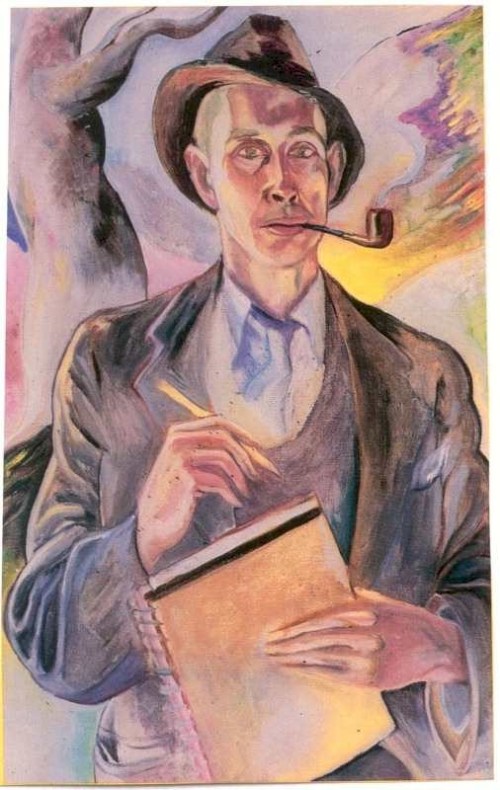

Glazunov also mentored, by the way,

Shostakovich at the Petrograd, proved

to be instrumental indeed in his

progress

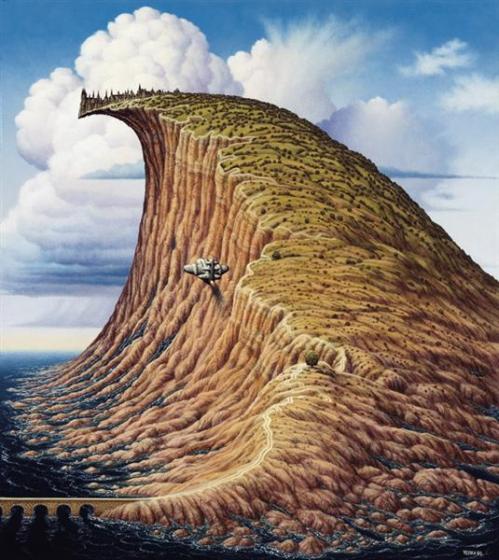

it’s interesting to put these last two

together, to compare, the Glazunov, 1881,

follows the traditional Romantic

imperatives, tempo, tonality and

repetition, but with more bombast, to my

mind, than its European counterparts,

its fields are the Russian steppes with

troikas, horse-drawn carriages, flying

across vast unhampered vistas of the

Russian snow-covered, therefore

pristine, tundra, to whet the unbridled

Russian spirit, the Europeans, Brahms,

Mendelssohn, Mahler, conversely,

are confined to the hunt, however ever

glorious, but with shrubs, copses,

thickets, if not veritable forests, to blur

the sonic arena, inspire dreams,

consequently, less far-reaching than

those of Johnny Appleseed even, of

the North American Prairies poets,

their own far-flung, boundless

imaginations, inspiration, you can

hear it all, blatantly, in the resonance

of the horns

you’ll note the movements follow

essentially the same rhythmic order

in either symphony, the first two fast

enough, then a third that’s somewhat

slower, a variation from the strictly

Classical order of fast, slow, fast, then

a last, eclectic, movement

but Shostakovich is more atonal,

melodically divergent, an eccentricity

he’ll later polish to a degree of

politically subversive brilliance

for not submitting, however, to the rule

of repetition, which is manifest, though,

in Glazunov, Shostakovich, I find, leaves

us trying to find our bearings as his music

rolls along, kind of like in biographical

movies, when you start looking at your

watch to determine how many life

incidents remain in this particular,

however significant, existential drama

as spectacle – and it must be noted that

symphonic displays were at the time

indeed spectacles – there was no

phonographic, photographic

equipment to transmit such

experiences, the symphony itself was

the show, it had, right there, itself, to

wow the audience

in all of these cases, all of them did

Shostakovich, however, of all of them

remained eventually potently

pertinent, powerfully paramount,

watch

R ! chard