String Quintets – Mozart / Beethoven

“A Cello“ (1921)

___________

between Bach’s transcendent Suites for

Cello and Beethoven’s reinvention of that

instrument, two only cello works occupy

the last half of that century, both by

Haydn

his Second, however, Concerto, written

several years later than his First, 1783,

indeed nearly twenty years later, seems

to me less accomplished, though ever,

nevertheless, unimpeachably, and

impressively, Haydn

the first movement is long, long works

only until you start thinking it’s long

the initial melody in the adagio, the

second movement, struck me as artificial,

saccharine, though Haydn weaves magic,

not unexpectedly, still, and

continuously, around it in its

development, his elaboration of it

and the pace of the third movement,

following the second, is disconcerting

rather than surprising, rather than,

were it effective, delightful

Mozart wrote a Cello Concerto too,

apparently, but, if so, it is lost

otherwise we’re on to the next historical

epoch, Beethoven’s, after this inauspicious

turn at this generation for the cello, lost

for a while among the more assertive

instruments of that prim, and proper,

Classical Era

R ! chard

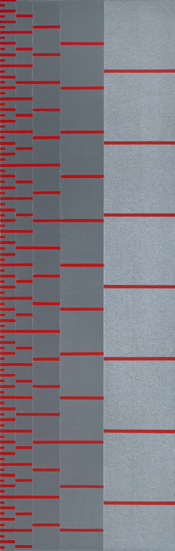

“Suite Fibonacci“ (2003)

________

before I say much more about his Cello

Suites, let me point out that Bach has

some French Suites, some English

Suites, on top of similarly structured

Partitas and Toccatas, the French have

their tout de suites, and hotels have,

nowadays, their so named luxury

apartments

musical suites are sets of dance pieces,

by the early 18th Century much stylized,

with an introductory prélude, an allemande,

followed by a courante, which is to say, folk

dances, the first German, the next French,

then a sarabande, Spanish, followed by a

couple of galanteries, court dances,

minuets, gavottes, bourrées, then a final

English gigue

all of the markings are in French, which

leads me to believe that all of these

dances must’ve originated at the court

of Louis XlVth, the Sun King, 1638 to

1715

but the suggestion is that Europe was

becoming an integrated community

all of these dances were eclipsed by

the Classical Period, of Haydn and

Mozart, apart from the minuet, which

more or less defined, nevertheless,

that new era

the minuet will die out by the time of

Beethoven, you’ll note, to be replaced

by the waltz, which had been

considered much too racy until

transformed by Chopin into a work

of ethereal art

the Strausses, father and son, gave it,

only a little later, celebratory potency,

but that’s another story

here’s Bach’s English Suite, the 3rd,

for context, the French ones are a

little too salty, as it were, they do not

quite conform to prescribed suite

notions, however might their

propositions have been, ahem,

sweet

meanwhile, enjoy this one

R ! chard

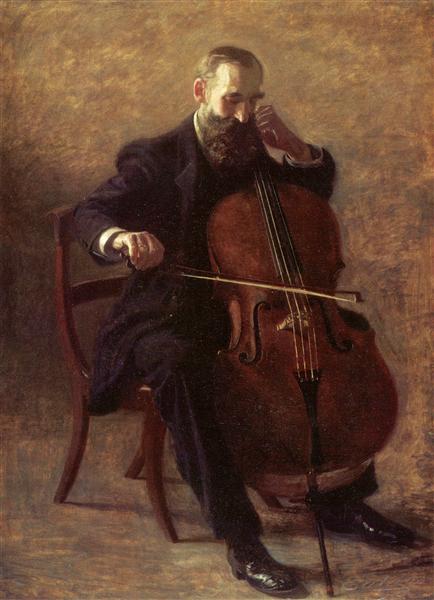

“The Cello Player“ (1896)

________

though I’d considered presenting all six

of Bach’s Cello Suites – your one stop

shopping for these extraordinary

compositions – even one only of these

masterpieces floored me each time I

individually listened

why the Suites, cause I couldn’t follow

up on Beethoven’s Opus 5, for cello

and piano accompaniment, without

saying more about the cello, by then

an instrument of some significance,

and who could argue, it’s resonance

thrills you in your bones, in your very

being

Frederick ll, King of Prussia, played it,

earning for him tailored compositions,

however controversial, from both

Mozart and Haydn, but even earlier,

Bach had composed definitive pieces

for it, much as he’d done for the

harpsichord, precursor to the piano,

students of either still go to Bach for

their basics, their intricate, exquisite,

technical proficiency

the cello can play one note only at a

time, which means that, like a voice,

you’re working without harmony,

you need to make your own,

otherwise your performance is

boring, no one else, as far as I know,

has ever written anything else for

unaccompanied cello, not even

Beethoven

I find most performers lend Bach a

more Romantic air, torrid emotion,

excesses of volume, pauses to the

pace, ritardandos, rallentandos,

which aren’t appropriate to the

more genteel Baroque period,

something I usually find

unwelcome

but in this performance, I’m sure

not even Bach would object

I’m offering up first the Sixth Cello

Suite, D major, played by Jian Wang,

someone I’d never heard of, in a

dazzling performance in Pyeongchang,

a place I’d neither ever heard of, until

only very recently

it appears both of these new kids on

the block ought to be on the map

R ! chard

“Prussian Homage“ (1796)

____________

it’s 1790, a year after the French Revolution,

and both Mozart and Haydn are peddling

their wares, Mozart to the King of Prussia,

Friedrich Wilhelm ll, who’d commissioned

some string quartets, as well as piano

works for his daughter, but wasn’t paying

Mozart off for them, where Haydn with the

help of Johann Tost, was hustling his stuff

in very, of all places, Paris

Haydn’s, incidentally, own Prussian Quartets,

dedicated to the same King of Prussia, were

sold to two different publishers, one in

Vienna, the other in England, commercial

transactions left essentially, for all it might

matter to us, for lawyers, and potentates, I

expect, eventually to have resolved

it is my habit to juxtapose two things always

to be able to see each more critically,

determining my favourite sharpens my

aesthetic pencil, one looks more closely at

what distinguishes one work from the other

therefore Mozart’s String Quartet no 22 in

B flat major, KV 589, up against Haydn’s

no 53 in D major, opus 64, no 5, “The Lark”,

both written in the same year

it’s like comparing apples with oranges,

different fruit from the same nevertheless

genus, my favourite being lichee, so go

figure

it’ll be up to you to find your especially

preferred nutrient

I‘ll just point out a few differences that

immediately set apart these, however

similar, masterpieces for me, Mozart

remains utterly Classical, relying on

the established, by now, conditions of

the string quartet, an entertainment for

nobility, nothing at all controversial,

where Haydn with his soaring notes

for the first violin, followed by

arabesques that define a personal

agony, introduces drama into the

equation, a music that speaks of

sentiment, is pointing already towards

the future, though I suspect he could

never have imagined where, in the

very next generation, Beethoven

would take it

to look back, to look forward, that is

the question, it’s not always an easy

one

but this is where art speaks to us,

reminding us of our tendencies,

defining, truly, eventually, who we

veritably are, according to our

individual choices, preferences,

for better or for worse, rendering

the world an ever effulgent garden

rather than a dour mausoleum

R ! chard

Cyprien Katsaris

________

if there’s only one concert you see

this week – I would’ve said this year

but I have way too many irresistible

concerts to promote – make it this

one, like none I’ve ever seen before,

Cyprien Katsaris, who wowed us in

my last encomium, delivers, not one,

but two concertos, when emotionally

I can usually deal with only one

but you can pause between the pieces,

like I did, to wipe a tear or two away

after the adagios, which remind me,

always, of my beloved, John

but that’s another story

Katsaris starts with an improvisation,

which he elucidates as an art form

much more expertly than I would,

then delivers a stunning rendition of

his mastery of that gift

though I couldn’t identify the first part

of it, the melting melody in the last

section of his homage to, essentially,

the Romantic Period, rushed back

memories for me of a piece I could

never forget, the music from Fellini’s

heartbreaking masterpiece “La Strada“

– listen, listen – right out of Romantic

Period idioms, its very story even, like

Dickens’ “Oliver Twist“, his Little Nell

from the “The Old Curiosity Shop“,

staples of my adolescence, married

to a nearly mythic lyrical invention

let me add that improvisations have

been an integral part of concertos for

a very long time, the cadenzas, an

interpolation by the performing artist,

hir riff, a strutting of hir stuff, late

in the, usually final, movement, a

consequence, incidentally, of the

more forward, individualistic,

18th-Century progression towards

individual rights, some left to the

performing artist, but many

prescribed by the composer himself,

where, here, I must, gender sensitive

myself, unceremoniously interject to

explain my deference to the

designation above, “himself“, to male

merely composers, who were then the

only ones, however culturally ignobly,

to nevertheless shape our quite, I

think, extraordinary musical trajectory,

for better, of course, or for worse

in this instance, I suspect Katsaris

wrote his own cadenzas for the

Mozart, notice his arm at the end of

the first movement fly up in an

especial transport, and in the last

movement, watch his very

exuberance mark the spot, but I

couldn’t put it past Mozart to have

written something so historically

visionary

Bach, incidentally, wasn’t doing

cadenzas, so don’t look for them

the two concertos that follow the

improvisation, Bach’s, my favourite

of his – you’ll understand why when

you hear it – then Mozart’s 21st –

everyone’s favourite – are both

played transcendentally

consider the difference in period,

the earlier Baroque, with Bach’s

notes skipping along inexorably,

the pace required by the

harpsichord, which didn’t have

hold pedals to allow notes to

resonate, the music moves along

therefore nearly minimalistic tracks,

a pace, and musical motif, that don’t

stop, they keep on chugging, until

they reach their destination, their,

as it were, station, or even their

stasis

Mozart’s music is as effervescent,

but conforms to a different cadence,

where a theme is presented, then a

musical, and contrasting, second,

with recapitulation, sometimes

merely partial, which is to say that

the call and response dynamic of

the dance, or for that matter, by

extension, modern ballads, is

being established, codified, and

elucidated

an era has intervened

then as an encore, Katsaris delivers,

not a cream puff, but Liszt, of all

people, we’re used to performers

giving us trifles at this point, but not

Katsaris

then to top it all off, he plays the Chopin

you thought you’d never ever hear again,

but here immaculate and utterly

inspirational

the orchestra alone performs after the

intermission, works by Ravel and Bizet,

surprisingly similar, I thought, the two

composers, in their musical idiom, the

use of the winds as metaphors, for

instance, for originality, eccentricity,

unmitigated poetry within the context

of what is not unnatural

neither is either composer adverse to

atonality, they work in textures, instead

of melodies, all of which is very

Impressionistic, see of course Monet

and others for historical reference

did I say I want to be Cyprien Katsaris

when I grow up, well there, it’s said,

he’s lovely

R ! chard

“Queen Marie Antoinette of France“ (1783)

Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun

___________________

first of all, let me grievously repent an

egregious confusion I probably left

in my last diatribe, I said that the second

movement of the Opus 54, no 2 sounded

to me like a minuet, I had, through

embarrassing inattention, confused its,

however unmemorable, adagio with that

of this Opus 55, no 3, which I’d listened

to in too quick succession, driven as I

am by my thirst for epiphanies

the Opus 54, no 2 will do, but I’m not

going back for seconds, nor to the

Opus 55, no 3, though here’s where

I flaunt nevertheless Haydn, not to

mention Bach, Mozart, Beethoven,

all the way to eventually Bruckner,

Brahms, the extraordinary Richard

Wagner, passing through Schubert,

Mendelssohn, the Strausses, father

and son, and the unrelated Strauss,

Richard, another incontrovertible

giant, and I nearly left out the

unforgettable Liszt, all of them

forefathers of our present music

you might have noticed that these

are all Germanic names, obedient

to the Hapsburg empire, with

Vienna as its supreme cultural

capital, and it was that

Austro-Hungarian dynasty that

indeed nearly single-handedly

secured our Western musical

traditions

a few Italians are remembered,

from the 18th Century, Scarlatti

maybe, Boccherini, Albinoni,

but not many more

no one from France, but they were

about to have a revolution, not a

good time for creative types,

though, incidentally, Haydn was

getting Tost, to whom he was

dedicating his string quartets for

services rendered, to sell his stuff

in very Paris

then again, Marie Antoinette, I thought,

was Austrian, an even archduchess,

and would’ve loved some down-home

music at nearby Versailles

so there you are, there would’ve been

a market

the English had Handel, of course,

who was, albeit, German, getting

work where he could when you

consider his competition, he was

too solemn and plodding by half,

to my mind, for the more

effervescent, admittedly Italianate,

continentals, Italy having led the

way earlier with especially its

filigreed and unfettered operas

but here’s Haydn’s Opus 55, no 3

nevertheless, the best Europe had

to offer, socking it to them

Haydn’s having a hard time, I think,

moving from music for at court to

recital hall music, music for a much

less genteel clientele, however

socially aspiring, we still hear

minuets, and obeisances all over

the place, despite a desire to

nevertheless dazzle, impress

then again, I’m not the final word, as

my mea culpa above might express,

you’ll find what eventually turns

your own crank, floats your own

boat, as you listen

which, finally, is my greatest wish

R ! chard

__________

if I haven’t spoken much about Bach

until now it’s that, although he is at

the very start of our modern music,

having in fact set up its very alphabet,

the scale we’ve been using since, he

is nevertheless as different from our

own era in music as Shakespeare is

to us in literature, both are stalwarts,

but we no longer say, for instance,

thee or thou, nor write in iambic

pentameter, nor do we dance

gavottes at court, nor congregate

at church to hear cantatas

the turning point is the Enlightenment,

also called the Age of Reason, when

the concept of God was being

questioned, if not even debunked, and

the mysteries of nature were being

rationally resolved, handing authority

to knowledgeable individuals instead

of to popes

by the time of Mozart and Haydn, a

secular tone was gradually pervading

all of the arts, devoid of any religious

intentions, sponsors were private

rather than clerical

Bach had indeed been hired by a prince,

Leopold of Anhalt-Köthen, but was

appointed court musician at his ducal

chapel, Nikolaus l, Prince Esterházy

wanted Haydn’s music, rather, for his

court entertainment, and for himself

as well, incidentally, as a fellow baryton

player

Mozart was also employed by a prince,

but left when he wasn’t being payed

well

times haven’t changed much, see

Trump, for instance

after the French Revolution, there was

not much call for religious music,

human rights took the place of God,

liberté, égalité, fraternité, and all that,

not to mention the American Bill of

Rights, and that’s the route we’ve

been following ever since, for better

or for worse

but hey, we’re still reading Shakespeare,

and still listening to Bach, and loving

both of them, some of us

here’s some more Bach for old times’

sake, his Partita no 2 for solo violin

a partita is just a series of dance suites

– an allemande, a courante, a sarabande,

a gigue, and a chaconne, in this case – I

don’t think anyone other than Bach ever

wrote some, but his are sublime

it’s kind of like my calling my own

stuff prosetry, for whatever infinity

that word might ever deliver, though

no one else might ever use that term

again

listen also to a transposition of its

celebrated last movement, the

Chaconne, for left-hand piano, in

this instance, as transposed by

Brahms, a precursor to Ravel’s

Concerto in G major for the Left

Hand, written for Paul

Wittgenstein, an already

accomplished pianist – the much

more famous philosopher,

Ludwig‘s, brother – who’d lost his

right hand during the First World

War, and who’d hopefully be

inspired, by such positive

reinforcement

art, music, poetry thrives on such

heartfelt expressions of sympathy,

compassion, communion

art is the faith that we rely on now

that God/dess is gone

R ! chard

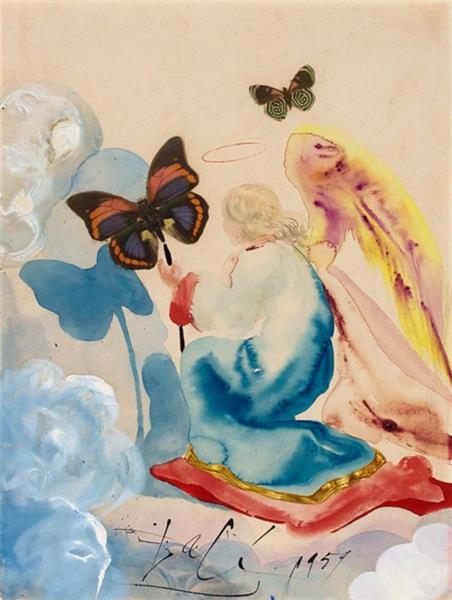

“Easter Angel“ (1959)

_______

for Elizabeth,

who needs an oratorio right now,

and who takes great comfort,

she tells me, in this music

if “The Seven Last Words of Our Saviour

on the Cross“ is not a divertimento, it

nevertheless didn’t come out of nowhere,

and a clue to its inspiration lies in the

eventual transposition of the orchestra

only piece to, a few years later, the piece

with voice, its oratorio

Haydn had heard his original composition

rendered in a nearby provincial town, where

they’d added lyrics, however saccharine, to

the score, and he thought it entirely effective

and appropriate, had new less sanctimonious

lyrics composed, and gave us what we now

hear

oratorios go back quite a while, not

surprisingly, they are quintessentially

religious music, meant to inspire, a

familiar convocational ploy, Bach and

Handel made them especially immortal

in the early 18th Century

listen to Bach’s “Easter Oratorio“ to see,

to hear rather, the connection to Haydn,

though you might not even notice much

significant difference, they’ve as many

movements more or less, nine for Haydn,

Bach’s has eleven, but all the forces are

the same, and in the same order

that Bach’s oratorio would be more

joyous is not surprising, the occasion for

the “Easter Oratorio“ is one of celebration,

where “The Words“ is more lugubrious, it

describes a portentous demise, dance

rhythms therefore are not in the former

inappropriate

its dances, however, are rather gavottes

and sarabandes instead of the later

minuets, a not not instructive alteration

when you think that minuets not much

later than Haydn had become waltzes,

more about that later

in the “Easter Oratorio“, the story is told

by the singers, whereas in “The Seven

Last Words“, the music is doing the

telling, secured by the fact that the piece

was originally written without singers

“The Words“ is more dramatic, more

use of contrasting volumes and tempi,

the piano hadn’t been invented at the

time of Bach, long notes couldn’t be

accommodated on the harpsichord,

which determined the pace of the plot,

the piano allowed with its soft pedal

a moderation in volume, and with its

hold pedal a moderation of a note’s

resonance, which allowed for more

expansive expression, which led

eventually, nearly inescapably, to

the Romantic Period, after passing,

of course, through, Mozart and

Haydn

but listen to what Bach can do

without these later interventions,

proof that a poet can inspire with

merely a matchstick, the second

aria itself – My soul, the spice that

embalms you shall no longer be

myrrh – for soprano and baroque

flute, spare as it is instrumentally,

is manifestly entirely worth the

priceless price of admission

R ! chard