sonatas, continued (Bach – “Goldberg Variations”)

“Lemons“ (1929)

___________

watching one of my cooking competition

shows on television the other day, the

twelve contestants were called upon in

pairs to create, each couple, one of the

six elements in a degustation menu

a degustation menu – I raised an eyebrow

at that one – is the same as a tasting menu,

but at a finer, it is implied, restaurant

the theme was citrus fruit, each service

had to highlight one of them, a mandarin,

a lemon, an orange, a lime, a tangelo,

a grapefruit, in that order

my goodness, I thought, a set of

variations on edibles, I was delighted,

not to mention synesthetically

titillated, all my senses were alive

the first course was a mandarin-cured

prawn ceviche, with pesto, something

to tease one’s palate, leaving plenty of

room, however, for what was to follow,

the second course, an equally light

lemon-cured salmon with smoked

crème fraîche and decorative

translucent radish slices, in again but

polite allotments

the third service introduces the protein,

duck with the nearly ever requisite

orange, but with beets, in this instance,

on an underlying sheen of all their

accumulated and colourful juices,

bread, I would imagine, would’ve been

gluttonously required

beef then followed, to fill the second

of the more substantial and filling

elements of the meal, with a lime

reduction and beets

for dessert, the fifth service presented

a tangelo cup with a surprise chocolate

truffle meant to burst in one’s mouth

with iced tangelo flavour, refreshing

and unexpectedly delightful, followed

by a grapefruit sorbet with chocolate

ganache and meringue shards as a

finale

not all contestants reached the heights

wished for, but some were memorable,

much as in any set of, even noteworthy,

variations

here’s Glenn Gould playing Beethoven’s

Six Variations in F major, Opus 34, each

variation is comparable to a culinary

experience, but for piano

listen, compare

these are preceded here by a late, and

haunting, Beethoven bagatelle, his

Opus 126, however, after which the

variations themselves are conveniently

spliced in the editing process to help

distinguish each movement from the

other

Glenn Gould doesn’t hit a note wrong,

but I think Beethoven’s introductory

aria, upon which the variations are

built, and which is repeated at the end

after a coda, or final interpolated wave,

is slow, a more engaging opening

would’ve been, to my mind, more

effective

I also would’ve, however peripherally,

degusted especially the lime beef

R ! chard

psst: incidentally, all Bach’s Cello Suites

are in six segments, their common

theme is dance, each one is a

scintillating Baroque example

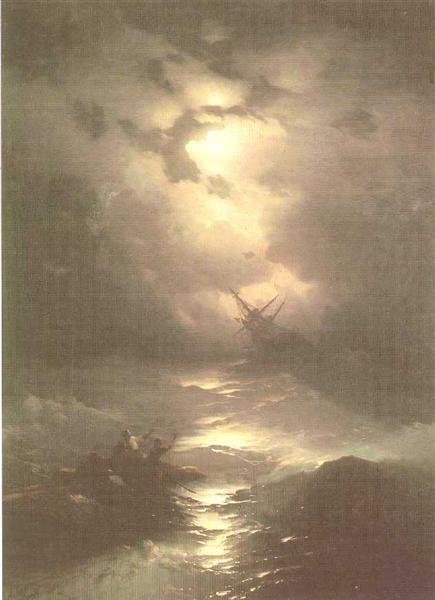

“Tempest on the Northern Sea“ (1865)

__________

for Judy, who “glimpses“, she says,

“a kinder world, that [my] missives

provide” – thank you, Judy

just as I was being called on the

carpet for my constant returns to

Beethoven, none other than Glenn

Gould should show up, in my

cavern of wonders, to absolve me,

or at least to stand stolidly by my

side

let him talk

had I written, however, his

observations, I’m sure you’d’ve

balked, he’s a product, after all,

of the priggish pretensions that

prevailed in my neck of the woods

at the time, Southern Ontario, a

product of British Imperialism,

of which I am myself, I avow,

incontrovertibly subject, but due

to the strength of his celebrity,

one is likely to listen to Gould

more attentively, I’m not

sufficiently yet, I suspect,

significant, nor influential

he is, one way or the other, I concur,

absolutely right

about his “Tempest“, though, I’ll say,

even object, as Stravinsky and John

Cage did, according to Gould, about

the commanding Beethoven, that

Gould is dripping in Romantic

sentiment here, his rubato in the

first movement tests the limits of

our forbearance, and his second

movement is so slow as to have

one fall off the page

but his last movement, the allegretto,

is brilliant

Gould’s idiosyncratic, dare I say,

eccentric, performance will

throughout, nevertheless,

astonish, indeed electrify, even,

I’m sure, inspire, watch, listen

and thanks ever, especially, for

dropping by

R ! chard

psst: here’s another version of the 17th,

to my mind, less self-indulgent, but

you be the judge, don’t think about

it, just ask yourself which one

would you want to hear a next time,

that’ll be your, gloriously personal,

reply

enjoy

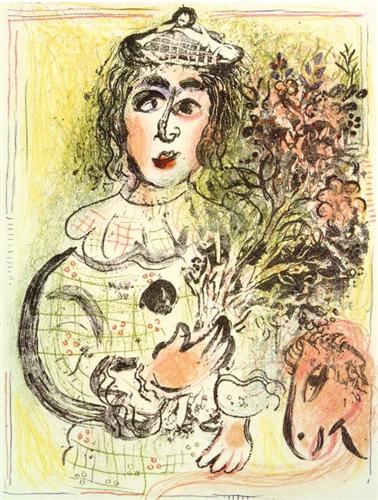

“Clown with Flowers“ (1963)

_______

with the greatest respect for all

who read me, and especially

for those who are least

convinced, the way also,

I note, to a conscious,

and entirely personal,

aesthetic

let me once again insist that my

commentaries here are not at all

the last word on any of what I’ve

discussed, they’ve been merely

my opinion, according to my own

particular aesthetic, my comments

have been rather to excite curiosity

about, for some, an esoteric topic,

to awaken interest in a field, to my

mind, strewn with marvels, and

never to dictate, art, as I often

remind, is in the eye of the

beholder

I think of myself as company in

an art gallery, viewing a

succession of works, musical

here, expressing notions, either

specifically to do with the exhibit,

or, personal, but somehow related,

then moving on, just enough to

whet the appetite, or, of course,

not

here’s an instance

I’d been waiting for the sales clerk

to box some fresh pasta for me I

was buying at an eatery down the

street when a line of piped in music

from their overhead system swept

me off my disconcerted feet, which

I recognized to be Mozart, but as

I’d never heard him, ever

can you tell me who’s playing that,

I asked the cashier, many stores

played their own tapes back then,

some still indeed even do,

19-eighty, at that time, something

he replied, Mitsuko Uchida

what she’d done was to not stress

the bar line, the natural beat, to,

in fact, eliminate it, so that a flight

of notes went on like an unfettered

and iridescent miracle, prompted

by its own irrepressible momentum,

I was flabbergasted

Beethoven later on would do that

nearly consistently

where Glenn Gould would remove

his foot from the sustain pedal to

channel Bach while he played

Beethoven, an atavism, Mitsuko

Uchida was reversing the process

and using Beethoven‘s own

unleashing of rhythms to shed

light on her Classically otherwise

bound Mozart, a telling

anachronism, I nearly screamed

here, in the event, is the next work

of musical art in my idiosyncratic

gallery, the richibi galleri, I call it,

Mitsuko Uchida herself illuminating

gloriously, as ever, Mozart, his

splendid, as she reminds us, Piano

Concerto no 9

thanks so much for stopping by

ever

R ! chard

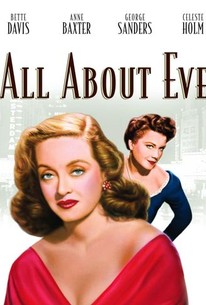

“All About Eve“ (1950)

_______

while I’m on the subject of concertos,

there’s one concerto that cannot be

overlooked, the very epitome of

concerti, their summit, apex, their

very pinnacle, Olympus, compared

to other less mighty compositions,

Beethoven’s Fifth Piano Concerto,

the piece I would take with me to a

desert island, I used to even walk

along the seashore in the privacy of

my headphones nights, after dinner,

taking in its cadences, its wisdom,

under the moon, the stars, along

the, however temperamental,

ocean waters, transported

indeed this very version of it, Glenn

Gould’s, Beethoven’s, in my mind,

oracular equal

Beethoven made literature out of

music, progressed to the point of

delivering a very philosophy,

Gould took the prevailing

Romantic aesthetic of the time,

Arthur Rubinstein being a prime

example, for instance, and gave

us the music of the Information

Age, the mathematical precision

of computers, people could hear

it, perhaps not even knowing how,

why

briefly, Gould eschews – Gesundheit –

the hold pedal, the sustain pedal, on

the piano, he’d grown up on Bach,

made him his specialty, but Bach

had no sustain pedal on his

harpsichord, Gould transferred this

process to later, more rhythmically

malleable, works, making obvious

thereby their inner workings,

something like reading blueprints,

his interpretations give us the bare,

and revelatory, bones of these later

masterpieces, without the sometimes

facile effects of Romanticism, think

of rubato, for instance, the ability to

stretch a note, not possible on the

harpsichord, but often overused in

Romantic renderings, a cheap trick,

like paintings on velvet

Gould would have none of that, he

shows you the composer’s

compositional brilliance, without

fanfare, just the facts, no pedal,

which at the time was completely

revolutionary, much like computer

science was then, and algorithms

here’s something else about Gould,

more savoury, maybe, he was called

in at the last minute to perform this

piece when the planned pianist, of

considerable renown, wasn’t able to

make it, Gould hadn’t played it in a

number of years, but showed up the

next morning to deliver, the rest is,

as they say, history

that’s “All About Eve“ up there, but

for pianists, Glenn Gould is Eve

Harrington, though without her

predatory instincts, nobody now

remembers the other pianist,

unless you were there, interested,

listening, piano’s Margo Channing,

even if I named him, however

consummately accomplished he

might’ve been, a man I profoundly

admire, remains, cruelly, essentially

unremembered

imagine

R ! chard

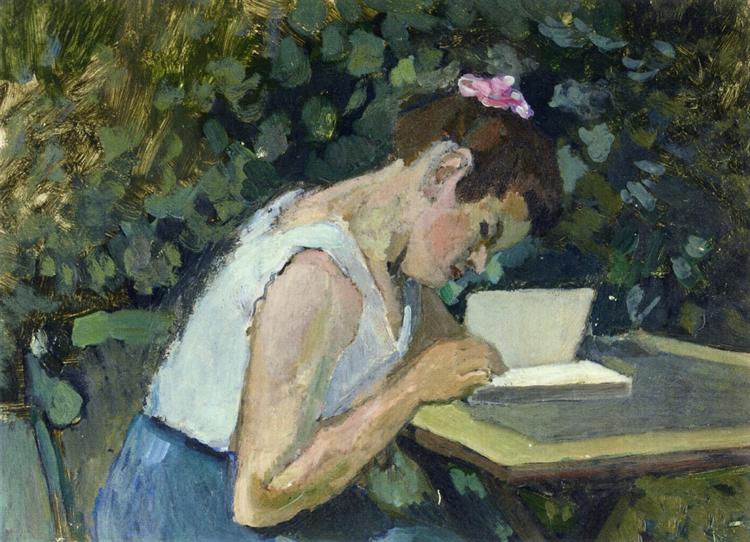

“Variations in Violet and Grey – Market Place“ (1885)

___________

strolling through my virtual musical park

today, in, indeed, the very merry month

of May, I was taken by surprise by, nearly

tripped over, in fact, a Beethoven work,

written in the very year, 1806, of the

“Razumovsky”s

I’d overlooked it cause it is without an

opus number, is listed, therefore, as

WoO.80, and is, consequently, easily

lost in the wealth of Beethoven’s

more prominently identified pieces,

but it is utterly miraculous, I think,

and entirely indispensable

I’d said something about it in an earlier

text, back when I was somewhat more

of a nerd, it would appear, perhaps even

a little inscrutable, though it’s

nevertheless, I think, not uninformative,

you might want to check it out, despite

its platform difficulties

the 32 Variations in C Minor are shorter,

at an average of 11 minutes, than Chopin’s

“Minute Waltz”, relatively, a variation every

half minute, where Chopin’s nevertheless

magical invention takes twice that to

complete its proposition

but in this brief span of time, this more

or less 11 minutes, Beethoven takes

you to the moon and back

a few things I could add to my earlier

evaluation, could even be reiterating,

Beethoven in his variations explores a

musical idea, turns it in every which

direction, not much different from what

he does in the individual movements of

his string quartets, his trios, his

symphonies, concertos and sonatas,

with their essential themes, motives,

they’re all – if you’ll permit an idea I got

from Paganini’s “Caprices” – cadenzas,

individual musings inspirationally

extrapolated, which, be they for

technical brilliance, or for a yearning

for a more spiritual legacy, set the

stage for a promise of forthcoming

excellence

this dichotomy will define the

essential bifurcated paths of the

musical industry, during, incidentally,

the very Industrial Revolution, their

mutual history, confrontation, for the

centuries to follow, which is to say,

their balance between form and

function, style versus substance,

Glenn Gould versus Liberace, say,

or Chopin, Liszt

before this, it’d been the more

sedate, less assertive evenings at

the Esterházys, to give you some

perspective, mass markets were

about to come up, not least in the

matter of entertainment

Beethoven was, as it were, already

putting on a show

R ! chard

psst: these alternate “Variations” put you in

the driver’s seat, a pilot explains the

procedures, it’s completely absorbing,

insightful, listen

“Masked Harlequin Violinists“ (1944)

________

the Opus 77, no 2, of Haydn is the last

full string quartet of his, his very last

remaining unfinished, the Opus 103,

written in 1803

Haydn died in 1809, the Opus 77, no 2

was composed in 1799, he would’ve

been 67

but by then, he had established the

form that music would take for the

next over two hundred years

call, response, and recapitulation is

the house that Haydn built, and verily

cemented, you can hear it in our own

period’s “Love Me Tender“, for

instance, if you’ll also permit me here

its irresistible elaboration, to today’s

top hits, like my own most recent

favourite such contemporary iteration,

released in 2014, “Photograph“

we could be listening otherwise to

Bach right now, counterpoint,

fugues, intricate, linear music,

however powerfully transcendental,

instead of recurring music, call,

response, as I said, and

recapitulation, something like how

a clock works

but already Haydn is testing the

waters, in the Opus 77, no 2, the

andante, a step up from an adagio,

is in third place, something we

haven’t heard before, and not, to

my mind, especially effective, like

his mixture of tempos in the Opus

54, no 2, which was disconcerting,

however masterfully resolved we

find those to be in this very Opus

77, no 2, notably in the second

movement’s “Minuet, Presto – Trio”,

where the tempo change is nearly

imperceptible

art works on contravention, but

the affronts are to established

conventions, which are very

hard to overturn

watch Haydn here continue to

do just that, for better or for

worse

R ! chard

psst: listen to Bach here, incidentally,

put his largo, or slow movement,

right where he wants to, at the

very top of the bill, does it work,

you tell me, a trivial pursuit,

you’ll ask, I say not, you are

defining your own aesthetic

sensibility, something

profoundly, I think, important,

who it is, with perspective, you

want to be

.jpg!Large.jpg)

“The Scream“ (1893)

____________

before we leave too far behind the

anniversary of the annihilation of

Hiroshima, August 6, 1945, let me

introduce you to a piece that

purports to pay it homage

if I didn’t bring it up before, it’s

because the date was wrong, but

especially because the work

offends me, the only thing I like

about it is the title, a thing of

beauty, poetry – Threnody to the

Victims of Hiroshima – a threnody

is a song of lamentation for the

dead, which worked for me, this

one, no further than its title

there is nothing remotely

reminiscent of the tragedy

throughout the piece, it is a

collection of academic exercises,

pretensions, I think, without a

heartbeat

let me compare Steve Reich’s

threnody to the victims of the

Holocaust, the other signature

Twentieth Century atrocity, his

“Different Trains“, a work in three

movements, “America – Before the

War”, “Europe – During the War”,

and “After the War”, for string

quartet and tape, upon which

Reich has recorded interviews

with people relating impressions

from before the war, during, and

after, according to the movements

the quartet, you’ll note, must keep

time with the tape, and in this

production visuals have been

effectively added

Glenn Gould had done something

like this several years earlier,

incidentally, in his “The Idea of

North“, a threnody itself to that

very idea, a masterpiece, a

groundbreaking transcendental

work of the imagination, with

overlapping voices, which is to

say human counterpoint, though

without string quartet

you’ll note that distressing tonalities

affect throughout this other, much

more successful however, tribute,

but the different rhythms of the

recurrent, which is to say minimalist,

rails keep you emotionally, as it were,

on track

“Different Trains“ is appropriately,

and profoundly, commemorative,

not to mention unforgettable

Richard

_______