November / Month of the Sonata – 7

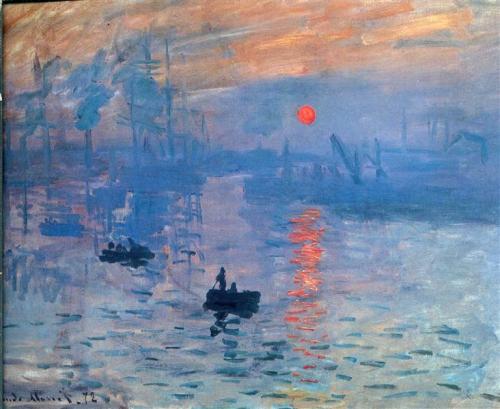

“Impression, Sunrise” (1873)

________

who’s afraid of the subjunctive

much like Elizabeth Taylor as Martha

in “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?”,

my answer is, I am, George, I am

the subjunctive is an esoteric mood,

even more abstruse in English than

in other languages, where the verb’s

conjugation highlights its presence,

in English, it’s nearly identical to the

indicative, the mood everybody

instinctively speaks in, facts

the subjunctive is about aspiration,

like the conditional, abstract, not

real, but its intention, rather than

the conditional’s inherent

impediment, a condition, shoots

for the stars, isn’t introspective,

but adamant, imperative

it is necessary that one be, it is

urgent that one have, it is

important that one effect, a

particular thing or event, all

subjunctives after the

doorkeeper word, “that”

one finds the subjunctive in

Shakespeare, master of grammar,

perhaps unparalleled in English,

a lot – O, that this too solid flesh

would melt, / Thaw and resolve

itself into a dew! – and follows

with Elizabeth Barrett Browning –

Pardon, o pardon that my soul

should make, / Of all that strong

divineness which I know / For

thine and thee …, for instance,

who is so profoundly indebted to

Shakespeare for her aesthetics

one wondrous day, I realized that

Proust’s entire “À la recherche du

temps perdu“, his “In Search of

Lost Time“, my Bible, was set in

the, French however, subjunctive,

the mood, there as well, of

possibility, therefore rather than

the definitive recreation of an

earlier time, Proust was

describing a sensibility, a personal

interpretation of a previous reality,

however bolstered by intimate and

apparently precise recollection of

shimmeringly imprecise, though

personally accurate, impressions

note here the similar preoccupations

of Proust’s contemporaries, the, aptly

named, Impressionists

everything, Proust was saying, as

were also the Impressionists, is in

the eye of the beholder

the subjunctive is the mood that

sets this instinct in motion

R ! chard

psst: Somerset Maugham I remember

being noteworthy as well for his

immaculate use, in his South

Pacific tales, of the subjunctive,

extremely elegant in its refined

construction, even with its

English austerities, like making

lace out of mere cloth, impressive

despite its impracticality, or

perhaps even because of it

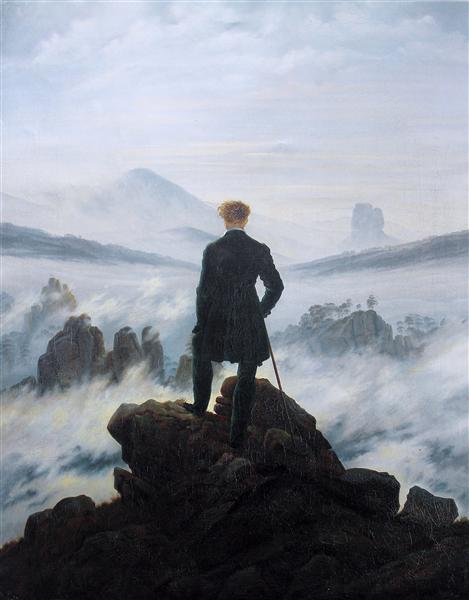

“The Wanderer above the Sea of Fog“ (1818)

_____________

if Beethoven built the Church, along

with Goethe maybe, of Romanticism,

and be assured Romanticism is an

ideology, a moral outlook, a

motivational perspective, much like

the economy is nowadays,

supplanting any more humanistic

imperatives, Brahms put up one of its

Cathedrals, just listen, the First Piano

Concerto is a monument, as mighty

as the Cologne Cathedral musically,

right next to Bonn, incidentally,

Brahms‘ birthplace

with the disintegration of the

supremacy of the Catholic deity

at the onset of the Protestant

Reformation, Luther, Calvin,

Henry Vlll and all that, bolstered

by new discoveries in scientific

speculation, that the earth wasn’t

flat, for instance, that it revolved

around the sun rather than the

other way around, contradictory,

though convincing, voices began

to abound, excite question

in the 18th Century, the Age of

Reason, the Christian Deity fell,

never effectively to be put back

together again, see for Its final

sundering, Nietzsche

in France, after the Revolution,

the Church was officially removed

from political consideration,

countermanding its centuries of

morally heinous depredations,

the United States had already at

its own Revolution separated it

from State

Romanticism was an answer to

a world wherein there might not

be a God, a world with, however,

a spiritual dimension, to respond

to the clockwork universe

envisioned by the earlier epoch,

the Enlightenment, a world where

everything could be categorized,

analyzed, predicted

Romanticism called for the

inclusion of inspiration in the mix,

there are more things in heaven

and earth, Horatio, than are

dreamt of in your philosophy,

as Shakespeare would, for

instance, have it – “Hamlet”,

1.5.167-8

poets became prophets thereby,

if they could manage it, very

oracles, the world was blessed

with, at that very moment,

Beethoven, far outstripping the

likes of, later, for example, Billy

Graham, or other such, however

galvanizing, proselytizers,

whose messages would’ve been

too, to my mind, literal

for music cannot lie, obfuscate,

prevaricate, music cannot be

fake

and then there was Schubert,

and Chopin, Tolstoy, Dickens,

Elizabeth Barrett Browning,

Robert, her husband,

Tchaikovsky, Caspar David

Friedrich, the Johann Strausses,

Byron, Shelley, Keats, whose

artworks, all, are as profoundly

in our blood, our cultural system,

as, if not more so than, our

present information about the

details of our Christian myths,

despite a superfluity of them

even, throughout the long

indeed Middle Ages, and right

up to, and including, the still

fervent then Renaissance, for

better or for worse still, for us

what Romanticism did, and

specifically through the work

of these seminal artists, was

give each of us a chance,

show us how to come

through trial and tribulation,

what a faith does, any faith

it said, here, this is my dilemma,

and this is how I deal with it

for me, Beethoven’s 32nd

Piano Sonata is, soundly, the

epitome of that, but listen to

Brahms put a stamp on it

with undaunted authority

we might be ultimately of no

consequence in an indifferent

universe, they say, but, hey,

this is what we can do, and

do gloriously, while we are

at it

Woody Allen picks up the

purpose in our own recent

20th Century, following in

the earnest footsteps of his

Existential mentor, the much

too dour, I think, Ingmar

Bergman

but that’s another story

entirely

meanwhile, listen

also watch, the conductor here,

a complete delight, is right out

of “Alice in Wonderland“, I

promise you’ll love it

R ! chard

“The Wanderer above a Sea of Fog“ /

“Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer“ (1818)

___________

for Collin, who’ll appreciate

especially, I’m sure, the

Chopin

while I’m on the subject of clarinet quintets,

since there are so few significant ones, let

me pull Brahms’ out of my hat and celebrate

it, a worthy challenge to Mozart’s own utter

masterpiece

but over a century has gone by, it’s 1891,

Beethoven, the French Revolution, the

Romantic Era is reaching its end, ceding

to Impressionism, after the disruptions of

rampant industrialization, and its

consequent effects on the social contract

Marx has proposed a theoretical master

plan to equitably protect the rest of us

from the 1%, however too politically

fraught, eventually, such a system – see

Communism

furthermore, Darwin had suggested that

we weren’t all descended from Adam and

Eve, but from larvae, which is to say,

millennially morphed, modified, through

time, genetically, leading to festering still

ideological objections

Elizabeth Barrett Browning had written

her unadulterated love poems to her

husband, Robert, Caspar David

Friedrich had shown us his wanderer’s

back while facing the mountainous

challenges of the upcoming world,

godless now after Nietzsche, Anna

Karenina had thrown herself in front

of a train, Madame Bovary had taken

poison, and Ibsen‘s Nora had left her

husband for a fraught, if not even

dangerous, life on her own, to escape

his safe but insufferable dominance,

while Jane Eyre was finding ghosts

in her cobwebbed, and insufferable,

to my mind, though admittedly

aristocratic, attic

you’ll note the clarinet is not sitting

centre stage, but has nevertheless

a place at the table, by this time,

though not not honoured, familiar,

and is more integrated to the

conversation, the idea of democracy

has taken hold, with everyone having

an equal, and even a vociferous, say

Brahms modelled his Clarinet Quintet,

on Mozart’s, the Classical structure is

still the same, movements, tonality,

musical recurrence, all to wonderful

effect

that he would do that is not a given,

but a tribute to the power of that form,

take the waltz for instance, alive from

even before Strauss, not to mention

Chopin, to approximately the middle

of the Twentieth Century

think about it, who waltzes anymore,

though they might’ve enchanted still,

residually, the 50’s – see Patti Page,

for instance – its lustre having

dissipated, with the wind, as it were,

the gust, before us, of the unending

ages

R ! chard

“Friends Since Childhood” (2004)

__________

having disparaged the only translation

I could find on the Internet of a poem

that is in French as famous as in

English Elizabeth Barrett Browning‘s

“How do I love thee? Let me count the

ways.“, her 43rd “Sonnet[ ] from the

Portuguese”, I decided to translate

myself the excerpt from “La Complainte

Rutebeuf“, of Rutebeuf himself, 1245 –

1285, which became its indelible, and

apparently timeless, virtual

manifestation

Rutebeuf’s entire poem is written in

Old French, and excerpts of it were

adapted into an updated French in

1956 by Léo Ferré, a French

troubadour of the time, who then

made it into a song that everyone

French remembers, despite, or

maybe because of, its archaisms

though Ferré familiarized the French

for his listeners, it was still in an older

French, like rendering Chaucer‘s

14th-Century English into Shakespeare‘s

17th-Century counterpart tongue, “But

look, the morn, in russet mantle clad, /

Walks o’er the dew of yon high eastern

hill”, “Hamlet”, act l, scene l, lines 166

and 167, for instance

in my translation below, I eschew –

Gesundheit – such a daunting

challenge, but have chosen rather

to highlight the humanity that I find

especially compelling in the original

composition

Rutebeuf today would sound

something of a cross between Harry

Nilsson and Bob Dylan, I think, of my

generation, the one for his

straightforward simplicity, his crushing

intimacy, the other for his social

consciousness and probable greater,

therefore, longevity

but will even Bob Dylan endure 800

years

some will, some have, some do

but who

we will never know

Richard

______________

Rutebeuf’s Lament

What has become of my friends

that I had held to be so close

and loved so dearly,

they were too carelessly tended,

I think the wind has blown them away,

friendship has been forsaken.

And as the wind passed by my door,

took all of them away.

As time strips the trees of their leaves,

when not a leaf on a branch remains

that will not hasten to the ground,

and poverty befalling me,

from every corner appalling me,

as winter edges on.

These do not lend themselves well to my telling

of how I courted disgrace,

nor of the manner.

What has become of my friends

that I had held to be so close

and loved so dearly,

they were too carelessly tended,

I think the wind has blown them away,

friendship has been forsaken.

And as the wind passed by my door,

took all of them away.

Sorrows do not show up on their own,

everything that was ever to happen

has happened.

Not much of common sense, a poor memory

has God granted me, that God of Glory,

not much in sustenance either,

and it’s straight up my butt when the North wind blows,

sweeping right through me,

friendship has been forsaken.

And as the wind passed by my door,

took all of them away.

Richard

“The Cellist (Portrait of Upaupa Scheklud)“ (1894)

_______

what are you reading, Terry asked,

I’d been riffling through the pages

of a book I’d just finished, trying to

find a particular bit I wanted for

firm ground later in conversations

a man in Sarajevo during the siege,

July 5, 1992 to February 29, 1996,

the bit I’d been looking for, had seen

neighbours, 22 of them, killed when

a mortar from the surrounding hills

had, as they waited in line for a much

depleted market, a consequence of

the siege, obliterated them, arms,

feet everywhere, as well as the

wounded

the man, a cellist with a Sarajevo

symphony, probably its finest, had

resolved, in honour of the victims,

to come out to play each day, at

the very time, in the very place of

the atrocity, for 22 days, one for

each of the victims, despite being

each time in the very eye of a

sniper’s bullet, Albinoni’s haunting

Adagio, listen

he made it out eventually to Ireland,

it is later indicated

“The Cellist of Sarajevo“, I replied,

I’m taking it back to the library, I

needed to check some dates, I

write, I want to talk about it

I’ve been talking about walking in

beauty, I said, incorporating it into

one’s life, this man overcame his

fear of death so profoundly as to

deliver a very dirge, an act of

prodigious, even transcendental

meditation, to sit and play midst

the rubble and ashes of his friends

this tribute, how sound must’ve

been his conviction

walking in beauty, I said, it’s a

Navajo prayer

Wordsworth has a poem like that he

said, and recited it word for word

“She walks in beauty, like the night

Of cloudless climes and starry skies;

And all that’s best of dark and bright

Meet in her aspect and her eyes;

Thus mellowed to that tender light

Which heaven to gaudy day denies.

One shade the more, one ray the less,

Had half impaired the nameless grace

Which waves in every raven tress,

Or softly lightens o’er her face;

Where thoughts serenely sweet express,

How pure, how dear their dwelling-place.

And on that cheek, and o’er that brow,

So soft, so calm, yet eloquent,

The smiles that win, the tints that glow,

But tell of days in goodness spent,

A mind at peace with all below,

A heart whose love is innocent!”, he said

I was flabbergasted, I had only my

few lines of Shakespeare to compare

I’m Richard, I said

Terry, he retorted

I can’t talk now, I’m off, if you can

believe it, to read Shakespeare with

a friend, we’ll meet again, you’re easy

to spot, you’ve got no shoes, you’re

barefoot, my mom has talked about

you, you always say hello, she says,

she thinks you’re a nice man

Terry had his sandals in his hand,

he stood under his umbrella, I

hadn’t opened mine, he was trying

to shield me also from, for me, the

merely mist, not rain, despite a

rod stretched unhooked from his

otherwise sufficient cover from

the wet

can you remember my e-mail, he

offered, it’s easy

I wrote it on the battered flyleaf

of my Shakespeare

that’s a relic, he said

my International Collector’s Library,

I answered, that’s where I got my

literature when I was a boy, in my

little town of Timmins, an outpost,

I’d get a classic every month, each

bound distinctively, their gimmick

you could get money for that, he

suggested

not, like this, I said, it’s in tatters

I’ll tell my mom I talked to you, I said,

she’ll be delighted

Tony, right

Terry, he corrected

Richard, I said

Richard

later he thought I’d been Michael

Richard

psst: it turns out the poem is by Byron,

not Wordsworth, not surprising,from

this distance all the Romantic poets

sound alike, except for, of course,

the Brownings, an inconsequential

gaffe

as the Beatles once sang, “Roll Over Beethoven“

I’d been touching up my blog, specifically my

Elizabeth Barrett Brownings, which WordPress

had to my dismay defaced, when one of my

submissions, the XXXlst, gave me the choice

of his “Appassionata“ or Patti LaBelle, to

accompany me on the dishes, my ritual

homage to Sisyphean labour before the

limitless

both are electrifying

but I opted for a change, the effect of, maybe,

springtime, chose Patti, who’d awakened by

her very name a world of magical memories

for me, even inspiring me to find finally a

long lost friend, an ardent fan, then, of Patti

I looked for an appropriate, concert, length,

enough to finish my dishes, this is what I

found

I’ve been hooked on divas ever since

I hope you’re also enjoying them

Richard

psst: more Patti

just when you thought you’d never see

Elizabeth Barrett Browning again, here

she pops up in, of all places, a movie

about Liberace, “Behind the Candelabra“,

a not undistinguished representation of

the high life, the over the top life, of an

aging and flamboyant superstar with his

much younger companion, feathers fly,

Ferraris too, and so do tempers

but at one point Liberace recites this

poem, “Why do I love you?”

where have I heard that line before, I

said to myself, and needed no one, of

course, to answer, here was Elizabeth

handing over her mantle to someone

in the XXlst Century, maybe

you decide

Richard

psst: Liberace also said, “too much of a good

thing is wonderful”, I’ll drink to that

__________________

Why do I love you?

Why do I love you?

I love you not only for what you are,

but for what I am when I’m with you.

I love you not only for

what you have made of yourself

but for what you are making of me

I love you for not ignoring

the possibilities of the fool in me,

and for accepting

the possibilities of the good in me.

Why do I love you?

I love you for

closing your eyes to the discords in me,

and for adding to the music in me

by worshipful listening.

I love you

for helping me to construct my life,

not a tavern, but a temple.

I love you because

you have done so much to make me happy.

You have done it without a word,

without a touch, without a sign.

You have done it by just being yourself.

Perhaps, after all,

that is what love means,

and that is why

I love you.

At Gate C22 in the Portland airport

a man in a broad-band leather hat kissed

a woman arriving from Orange County.

They kissed and kissed and kissed. Long after

the other passengers clicked the handles of their carry-ons

and wheeled briskly toward short-term parking,

the couple stood there, arms wrapped around each other

like he’d just staggered off the boat at Ellis Island,

like she’d been released at last from ICU, snapped

out of a coma, survived bone cancer, made it down

from Annapurna in only the clothes she was wearing.

Neither of them was young. His beard was gray.

She carried a few extra pounds you could imagine

her saying she had to lose. But they kissed lavish

kisses like the ocean in the early morning,

the way it gathers and swells, sucking

each rock under, swallowing it

again and again. We were all watching —

passengers waiting for the delayed flight

to san jose, the stewardesses, the pilots,

the aproned woman icing cinnabons, the man selling

sunglasses. We couldn’t look away. We could

taste the kisses crushed in our mouths.

But the best part was his face. When he drew back

and looked at her, his smile soft with wonder, almost

as though he were a mother still open from giving birth,

as your mother must have looked at you, no matter

what happened after — if she beat you or left you or

you’re lonely now — you once lay there, the vernix

not yet wiped off, and someone gazed at you

as if you were the first sunrise seen from the earth.

The whole wing of the airport hushed,

all of us trying to slip into that woman’s middle-aged body,

her plaid bermuda shorts, sleeveless blouse, glasses,

little gold hoop earrings, tilting our heads up.

Ellen Bass – from “The Human Line” (2007)

_____________________

the line, as it were, is blurred here between

prose and poetry, what is the one and what

is the other, the answer, of course, is in the

eye of the beholder, what do you think

I cannot profess to be able to give you an

answer, to be able to tell you your difference,

I can only know what I know, and how that

accords with what I think poetry is, or

prose, for that matter, what for me are

their definitions

these have been tested, much as my

definitions of love, for instance, or

friendship as well, throughout my ages,

and for the very same reasons, to get to

know myself, to somehow learn there life’s

lessons, for art and affections have been

the most profitable sources of my

metaphysical scrutiny, who am I, where

am I, and why, these and ill health, and

the looming inexorability of its

consequence, of course, death

a simple answer to the question, is

“Gate C22“ a poem, would be that it is

written in iambic pentameter, like

Shakespeare, like Elizabeth Barrett

Browning, and a host, of course, of

others, if that is for you sufficient

grounds to validate, not to mention

its metaphors, even allegories,

alliterations, onomatopeiae

the more difficult answer is in its

articulation, its condensation and

distillation, of a very magical and

immutable, perhaps even oracular,

moment

which, for me, already, is, in and of

itself, very poetry

but I’m a poet, I look for stuff like

that, you’ll have to forgive me

that idiosyncrasy, it has provided

me ever, however, with wonders

Richard

psst: loved “vernix“, who knew