nocturnes / scherzos, Chopin

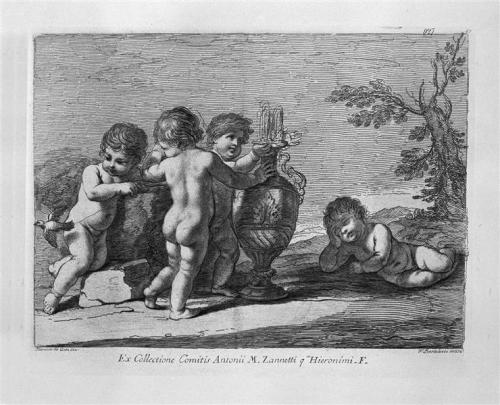

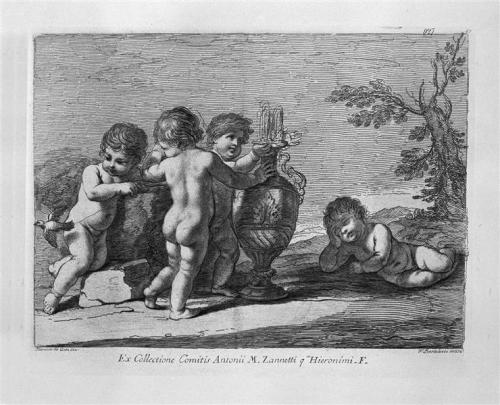

“Scherzo di putti“

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

______________

two, a scherzo

you tell me

both by Chopin

two, a scherzo

you tell me

______________

if I’m including Tchaikovsky’s Third,

and last, Piano Concerto in my survey,

it’s not because of its excellence, it is,

indeed, severely flawed, but because

I am a completist – if I’m visiting the

Cologne Cathedral, ergo, for instance,

I’ll make my way to the very top,

however treacherous might be the

stairs, the gargoyles being worth it,

not to mention the view

first of all, it’s incomplete, Tchaikovsky

died before finishing it, you can’t blame

him for that, though he was, curiously,

complicit in his own demise, but I don’t

believe this composition and his death

are that intimately interrelated

it has only one movement, but has

nevertheless been termed a concerto

on the, debatably unsound, strength

of its intention

briefly, and this is my opinion, the

movement has no lyrical moment,

no melting melody to float you out

of the recital hall as you exit,

nothing to hum, nor to whistle as

you wistfully wend your way back

home, nothing to remember but

flash, braggadocio, bombast,

expert fingers strutting their

dazzling, even, stuff, style over

substance, I venture, won’t be

enough to whisk you into the

following centuries

Chopin, the other towering Romantic

figure standing between the spiritual

bookends of Beethoven and Brahms,

wrote two piano concertos, of which

his Second suffers from, essentially,

not being his First, however mighty

his Second here, for instance,

proves to be in this utterly convincing

performance, watch, wow

Beethoven, in other words, wrote the

book, two works, Tchaikovsky’s First

and Chopin’s First, tower above his

in the public imagination during the

ensuing High Romantic Period, after

which Brahms closes the door on the

era with his two powerful masterpieces

for piano and orchestra

of which more later

there are other piano concertos

along the way, but Beethoven’s

five, Tchaikovsky’s and Chopin’s

one each, and Brahms two are

the basics – but let me add, upon

further consideration, and for a

a perfect ten options, Liszt, his

own, of two, First Piano Concerto –

what you need to consider yourself

comfortably aware of the essentials

of music in the 19th Century, the

culture’s predominant voice then,

until art, painting, took over as the

Zeitgeist‘s most expressive medium

with Impressionism

of which more later

R ! chard

“The Birth of Venus” (1485)

___________

if there’s a piano concerto that dominates

the 19th Century, it’s Tchaikovsky’s First

Piano Concerto, not even Beethoven’s

Fifth, to my mind, matches its celebrity,

one thinks Romantic Period, one thinks

this iconic masterpiece

Tchaikovsky had the advantage of

absorbing not only Beethoven by this

point in history, but also Chopin, the

narrative power of the former, with

the mesmerizing textures of the latter,

what could go wrong but insufficient

genius

of which Tchaikovsky manifestly had

more than plenty, enough to verily

stop your breath

many towering performers have

challenged this concerto‘s peaks,

some even historically, you’ve

heard them, I won’t reiterate

but listen to what Yuja Wang does with

this challenge, and you tell me if she

doesn’t conquer its tribulations,

despite, or abetted by, her

controversial dress

she is a vixen, manifestly, at least in,

admittedly, her attire, but should a

vixen play as brilliantly, what does

one have to counter her provocative

presentation but her innate femininity,

her, too often castigated, female pulse,

something the world could do with a

lot more of

Venus, with all her allure, was goddess

for centuries before women were

obliterated from the dominant Christian

pantheon, the Father, the Son, the Holy,

I ask you, Ghost, with no equal female

foundational representative

Yuja Wang, a modern day Venus abetted

by her evident attendant muses, the

symbolic, here, orchestra, see above,

could play nude, as far as I’m concerned,

she’d still be transcendent, and I’m not

even heterosexual

girlfriend, I say, however proper, modest,

blushing, get a grip

not to mention that Tchaikovsky is also,

in this outing, once again, astounding

R ! chard

“Chopin Performing in the Guest-Hall of Anton Radziville in Berlin in 1829”

(1887)

________

Chopin’s Piano Concerto no 1, written

in 1830, is in the same mold as both

the Beethoven Violin Concerto, 1806,

and Paganini’s 5th, a synchronous

1830, three movements, fast, slow,

fast, a long symphonic introduction,

followed by miracles of articulation

by the virtuosic soloist, with, however,

differing degrees of emotional impact

Beethoven is evidently the source,

and model, for both later compositions

having clearly preceded them by a

number of years, but neither Chopin

nor Paganini have the chops to match

his magisterial orchestration

Chopin, like Paganini, was confined to

essentially one instrument, of which,

however, both were utter masters, and

manifestly and profoundly there inspired,

but in either, once the solo part takes

flight, the symphony is merely

packaging, no longer an equal partner

Beethoven has parts for all his players,

his is a conversation, not a declamation

but Chopin, 1830, had learned by then,

and integrated from Beethoven the

lesson of how to incorporate drama

into his high wire act, the constant

repetition of a melting air, a musical

motive, which Paganini hadn’t, Chopin

not only could fly, but also knew how

to dress for it, to become a virtual

angel of mercy and compassion up

there under the biggest of tops, his

immortality

don’t take my word for it, though,

you’ve probably heard already Chopin‘s

work, a very emblem of 19th Century

Romanticism, somewhere in your

subconscious you know this melody,

heard it before, it’s part of our Western

culture

not so the Paganini

what’s kicked

see above

you’ll hear your senses talking, the

language of music and art, more

accurate eventually than any of my,

however erudite, however informed,

but merely ruminative, words, art

being, once again, in the eye, the

ear, in this case, of the beholder,

or here, the be-hearer

listen

R ! chard

“Owl on a Grave” / “Eule am Grab“ (c.1836 – c.1837)

_______

following my nose rather than

my intellect in my exploration

of musical treasures, like a very

Aladdin uncovering at the click

of my password a cave full of

priceless wonders, I might find

stuff out of sequence, but gems

nevertheless, and I can’t just

whisk by without acknowledging

them, however peripheral to my

main task

it’s like heading towards the Eiffel

Tower in Paris, and not stopping

at the Arche de Triomphe

though I’d debated so soon

presenting these two pieces,

not because of their chronology

especially, though also that, but

mostly because of their dour

content, I’ll point out that the

move from Classicism to

Romanticism is the transition

from dance music, delightful

music, to drama, passion,

powerful emotions, dirges,

therefore, are not out of place,

however mournful

thus the two most famous

funeral marches, Beethoven’s,

Chopin’s, the third movement

in either of their home sonatas

the clincher for me was the

immaculate performance of

the Chopin here, a revelatory

moment, though the Beethoven,

significantly earlier, the tune,

1801, 1837, is nevertheless

unimpeachable, however still

underdeveloped – four variations

only in the first movement, for

instance, and all of them

elementary – the caterpillar had

not yet become the butterfly, the

apple blossom the apple

note that each movement in the

Chopin, apart from the last, has

two distinct tempi, executed

effortlessly and nearly

imperceptibly, a total of six, you

can’t see, you can’t hear, the

seams as you listen, which, with

its virtual therefore episodes,

conflicting and tortuous

emotions, constitute collectively

a drama, a narrative, music has

become literature

the last movement of the Chopin

moves beyond even tempo –

Beethoven’s also, incidentally,

nearly – creating therefore a

very challenge to it, both trying

to transcend tempi, an area to

closely watch

Beethoven’s Piano Sonata no 12

take your pick

both are supremely, mark,

instructive

R ! chard

“The Minuet“ (1866)

_________

having pointed out that the minuet

and the waltz were historically

related, let me somewhat

extrapolate

they are both in 3/4 time, which is

to say, three quarter-notes to the

bar, which means that when

you’re dancing, your beat is one,

two, three, one two three, with

the accent, usually, on the first

note

so what happened, how could two

identical frameworks turn out so

differently

here’s Bach, 1725, his Minuet in G

the first thing you’ll think is, o, so

that’s what that is, it is an iconic

number written on our collective

consciousness

the second thing you’ll notice is

that it is choppy, however delightful,

that it is written for a harpsichord,

and that it’s probably not ready,

despite it’s 3/4 time, to be a waltz,

too many curtsies

here’s Mozart, 1762, his Minuet in G

though you might not want to admit

it, I suspect this number is much

more present in your subconscious

than you’d think, see if you don’t

find yourself later on humming it

but it’s still way too polite to be a

waltz, you can easily imagine the

partners, hands held high together

around their imaginary maypole,

courting, but there’s a touch more

fluidity in the progression of the

notes, it is written for a fortepiano,

an instrument that has added the

hold, or the sustain, pedal to the

harpsichord to increase a note’s

resonance, a loosening of the

earlier constraints of that

quintessentially Baroque

instrument, a cannily apt

metaphor, take into account, for

the unfolding cultural r/evolution

here’s Beethoven, 1796, his Minuet

in G, you’ve heard this one too

the Revolution has taken place,

but entrenched in the music of an

earlier era, the beat remains the

same, this is not a waltz, despite

it’s 3/4 progression

you’ll note, however, more spin

to the cadences, more give, more

elasticity, much of this has to do

with the development of the

central instrument, which was

about to become a pianoforte,

instead of a fortepiano, but

‘nough said about that, I’ll let

you feel it

here’s Chopin, 1833, his Grande

valse brillante, Opus 18, written

for itself, the piano, it is indeed

a waltz, the difference is in the

piano’s ever evolving flexibility,

again a metaphorical expression

of, or an avatar for, the unleashing

of personal freedom, an idea spun

ineradicably from the lessons of

the French, and the, incidentally,

nearly simultaneous, 1776, 1789,

American Revolutions

for better or for worse

R ! chard

“Waltz“ (1891)

________

inadvertently, during my last comments,

I let slip, perhaps, prematurely – cause I

thought I’d explore earlier Romantic

pieces first, more Beethoven, more

Paganini – the word waltz, when I

referenced the “Minute Waltz”, a dance

which expressed a sea change in

Western cultural history made

manifest through music

though the waltz was already the rage

in lowlier social circles in the late

1700’s, the minuet still held sway in

the more aristocratic salons, whose

young swains nevertheless would

skip out to ferret out the servants’

quarters, as young swains do

slowly the dance, for its more

informal aspects, not to mention

its sensuous intimacy, became so

astonishingly mainstream as to

define pretty well the very century,

Chopin and the Strausses, Father

and Son, would take care of that,

the last two making a carnival out

of very Vienna

but until the late 1820’s, not much

was heard of the waltz in the

musical curriculum, at which

point it’ll come in with a vengeance

not much from Beethoven, who, in

his fifties, was probably about as ,

interested in waltzes as I am in hip

hop, a ditty only, a trifle, this one,

1824, one of only two waltzes

from him

here’s Johann Strauss l, however,

his “Carnival in Venice“, 1828, is a

waltz in “Carnival“ clothing, like

cadenzas, for instance, in the

guise of Paganini “Caprices”

here’s Johann Strauss ll, the son,

with his “Wiener Blut“, “The Spirit

of Vienna“, electrifying, 1873, the

late already 19th Century

but here’s Chopin doing his stuff,

1847, right in the middle of both,

from far away Paris, which was

going through its list of Empire

changes right about then, his

Waltz in C-sharp minor

Chopin’s waltz is a more decorous

composition, more courtly, more

also introspective, contemplative,

private, indeed Romantic

note how strongly the Classical

unities still apply here, tempo,

tonality and repetition, even more

markedly than in Beethoven, Chopin

is Mozart, but with more sentiment,

and perhaps more rubato, stretching

the rhythm in composition to

accommodate a dancer’s presumed

dip, in his otherwise meditational

compositions

the waltz will undergo trials and

tribulations later, as the world

turns, but I’ll keep those

reflections for later

meanwhile, choose your partner

R ! chard

“Variations in Violet and Grey – Market Place“ (1885)

___________

strolling through my virtual musical park

today, in, indeed, the very merry month

of May, I was taken by surprise by, nearly

tripped over, in fact, a Beethoven work,

written in the very year, 1806, of the

“Razumovsky”s

I’d overlooked it cause it is without an

opus number, is listed, therefore, as

WoO.80, and is, consequently, easily

lost in the wealth of Beethoven’s

more prominently identified pieces,

but it is utterly miraculous, I think,

and entirely indispensable

I’d said something about it in an earlier

text, back when I was somewhat more

of a nerd, it would appear, perhaps even

a little inscrutable, though it’s

nevertheless, I think, not uninformative,

you might want to check it out, despite

its platform difficulties

the 32 Variations in C Minor are shorter,

at an average of 11 minutes, than Chopin’s

“Minute Waltz”, relatively, a variation every

half minute, where Chopin’s nevertheless

magical invention takes twice that to

complete its proposition

but in this brief span of time, this more

or less 11 minutes, Beethoven takes

you to the moon and back

a few things I could add to my earlier

evaluation, could even be reiterating,

Beethoven in his variations explores a

musical idea, turns it in every which

direction, not much different from what

he does in the individual movements of

his string quartets, his trios, his

symphonies, concertos and sonatas,

with their essential themes, motives,

they’re all – if you’ll permit an idea I got

from Paganini’s “Caprices” – cadenzas,

individual musings inspirationally

extrapolated, which, be they for

technical brilliance, or for a yearning

for a more spiritual legacy, set the

stage for a promise of forthcoming

excellence

this dichotomy will define the

essential bifurcated paths of the

musical industry, during, incidentally,

the very Industrial Revolution, their

mutual history, confrontation, for the

centuries to follow, which is to say,

their balance between form and

function, style versus substance,

Glenn Gould versus Liberace, say,

or Chopin, Liszt

before this, it’d been the more

sedate, less assertive evenings at

the Esterházys, to give you some

perspective, mass markets were

about to come up, not least in the

matter of entertainment

Beethoven was, as it were, already

putting on a show

R ! chard

psst: these alternate “Variations” put you in

the driver’s seat, a pilot explains the

procedures, it’s completely absorbing,

insightful, listen