November / Month of the Sonata – 27

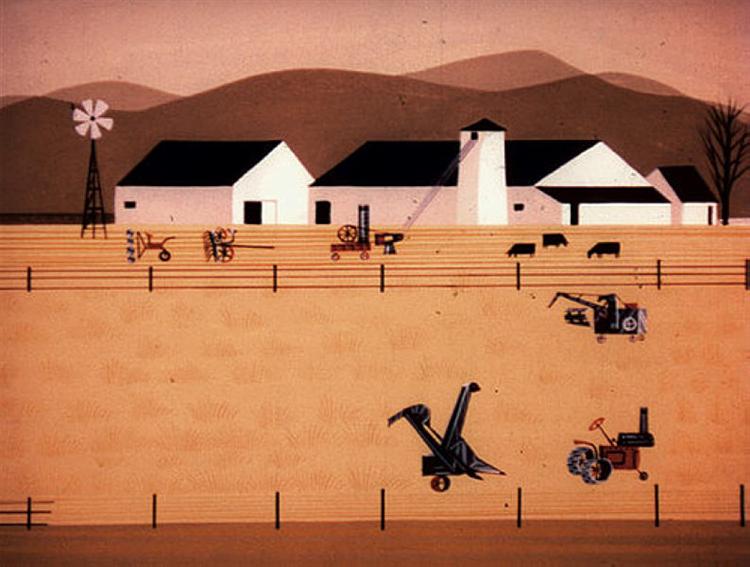

“Rhapsody of Steel“ (1959)

________

so what’s a rhapsody

“The Violin“ (1916)

_____

if I was able to bring up a list of

ten top Romantic piano concertos

throughout the 19th Century earlier,

I can number of violin concertos

only three essential ones, with,

however, two other significant

such compositions, which remain,

for one reason or another,

peripheral, secondary

more about which later

but the exalted three are situated

conveniently, the first, at the very

beginning of the Romantic Era,

Beethoven’s magisterial, even

extraordinary, Opus 61 in D major,

1806, and close doubly with the

two others, Tchaikovsky’s

resplendent work, words cannot

do it justice, and Brahms’ no less

transcendental one, at its very end,

1878, none are negligible, it’d be

like missing the Eiffel Tower while

in Paris, skipping the pyramids

along the Nile, they are part of our

cultural consciousness, it would

be an utter shame to pass them

by, they are our glory, our

magnificent heritage

it should be noted that the

concerto, be it for violin, piano,

cello, what have you, a soloist

in concert with an array of

instruments, is the perfect allegory

for the Romantic Era, an individual

in contention with a community,

under the influence of a conductor,

a mayor, a mentor, a polity, the

individuality afforded by the

proclamation of human rights in

the aftermath of the French

Revolution, and its social

consequences, musically

manifested

the match might be fraught,

should be, though with

compromise, considerate

accommodation, fruitful,

hopefully even transcendental,

if not at least entertaining,

cooperation, music seems to

infer eventual concord,

congress, harmony, a way out

of, even dire, distress, or at

least point the way toward it

concertos die out, incidentally, in

the 20th Century, you don’t hear

of very many, if any at all, after

Rachmaninoff, they are gone,

much like later, in the 1950s, the

waltz, forever, with the wind

may they rest in peace

R ! chard

“Liberty Leading the People“ (1830)

_________

for everyone, with great gratitude,

who reads me, I mean only to

bring poetry, which is to say,

light

though I’d considered leaving the

Romantic Piano Concertos behind

to explore other areas of the period

in this survey, it seemed unfair,

indeed remiss of me, not to include

the three among my top ten that I

haven’t yet highlighted, Beethoven’s

2nd, 3rd, and 4th Piano Concertos,

Opuses 19, 37, and 58 respectively,

after all, these are where the spirit

of the age, the Zeitgeist, was

constructed, like a building, with

walls, windows, a hearth, all of

which would become a church,

then a Church, and by the time of

Brahms, a very Romantic Cathedral

the foundation had already been laid

by Mozart with his 27, but music had

not yet become anything other than

an entertainment by then, or

alternatively, an accessory to

ceremonial pomp and circumstance,

see Handel and England for this, or

liturgical stuff, see, among many

others here, Bach

but with the turn towards

independence of thought as the

Enlightenment progressed, cultural

power devolved from the prelates,

and their reverent representations,

to the nobles, who wanted their own

art, music, which is to say, something

secular, therefore the Classical

Period, 1750 – 1800, in round figures

then in the middle of all that, 1789,

the French Revolution happened,

and the field was ripe for prophets,

anyone with a message of hope,

and a metaphysical direction, midst

all the existential disarray – the Age

of Reason had set the way,

theoretically, for the possibility of a

world without God, something, or

Something, was needed to replace

the The Trinity, the Father, the Son,

and the Holy Ghost, Who had been

seeing Their supremacy contested

since already the Reformation

Beethoven turned out to be just

our man, don’t take my, but history‘s

authentification of it, see the very

Romantic Period for corroboration

in a word, Beethoven established a

Faith, a Vision, not to mention the

appropriate tools to instal this new

perspective, a sound, however

inherited, musical structure – his

Piano Concertos Two, Three, and

Four, for instance, are paramount

amongst a host of others of his

transcendental revelations

briefly, the initial voice, I am here, in

the first movement, is declamatory,

even imperious, but ever

compositionally solid, and proven,

tempo, tonality, recapitulation, the

materials haven’t changed from the

earlier Classical epoch, just the

design, the interior, the

metaphysical conception

his construction is masterfully

direct, the line of music is

throughout ever clear and concise,

despite flights of, often, ethereal,

even magical, speculation, you

don’t feel the music in your body

as you would in a dance, as in the

earlier era, of minuets, but follow

it, rather, with your intellect, you,

nearly irresistibly, read it

but the adagio, the slow movement,

the middle one Classically, is always,

for me, the clincher, the movement

that delivers the incontrovertible

humanity that gave power to the

Romantic poet, who touched you

where you live

Beethoven says life is difficult, and

eventually, at the end of his Early,

Middle and Late Periods, life may

even have no meaning

but should there be someone, he

says, who is listening, Someone –

though implicit is that one may be

speaking to merely the wind – this

is what I can do, this is who I am

and while I am here, however

briefly, I am not insignificant, I

can be worthy, even glorious,

even beautiful, I am no less

consequential, thus, nor

precious, than a flower

for better, of course, or for worse

R ! chard

_____________

if Brahms’ 2nd Piano Concerto is, to my

mind, the last one of the Romantic Period,

Beethoven’s First is, accordingly, the first

I thought it, therefore, instructive to pair

them

Beethoven, impelled by ideological

speculations, built not only a variation

on what had come before, music as

entertainment, a reason to dance, but

gave it a greater, which is to say,

philosophical, dimension

by extending the reach of the cadence

beyond the usual metered rhythm,

sending the melodic statement

beyond an otherwise constricting bar

line, Beethoven turned a lilt into a

sentence, a ditty into a paragraph

Shakespeare does the same thing to

poetry, for instance, with iambic

pentameter devoid of rhyme

“But, soft! what light through yonder window breaks?

It is the east, and Juliet is the sun.

Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon,

Who is already sick and pale with grief,

That thou her maid art far more fair than she”

and with this newfound oratory,

peremptory, insistent, imbued,

however, with utterly convincing

honesty, unfettered emotion,

which is to say, humanity,

Beethoven establishes the

sensibility of a very era, listen

that era, up to, eventually, Brahms,

elaborates on that ethos, adding

texture and enhanced authority

to the original concept, setting

the moral agenda for that, and

other generations, to follow

Brahms is more ponderous, mighty,

a cathedral instead of a church, a

commandment instead of an

aspirational, merely, thrust, he

adds even a fourth movement to

an already magnificent structure,

an extra steeple to a towering

edifice, a subliminally received

reference to Beethoven‘s already

inspired, but tripartite only,

architecture

see Chartres for a comparable

ecclesiastical counterpart

R ! chard

______________

if I’m including Tchaikovsky’s Third,

and last, Piano Concerto in my survey,

it’s not because of its excellence, it is,

indeed, severely flawed, but because

I am a completist – if I’m visiting the

Cologne Cathedral, ergo, for instance,

I’ll make my way to the very top,

however treacherous might be the

stairs, the gargoyles being worth it,

not to mention the view

first of all, it’s incomplete, Tchaikovsky

died before finishing it, you can’t blame

him for that, though he was, curiously,

complicit in his own demise, but I don’t

believe this composition and his death

are that intimately interrelated

it has only one movement, but has

nevertheless been termed a concerto

on the, debatably unsound, strength

of its intention

briefly, and this is my opinion, the

movement has no lyrical moment,

no melting melody to float you out

of the recital hall as you exit,

nothing to hum, nor to whistle as

you wistfully wend your way back

home, nothing to remember but

flash, braggadocio, bombast,

expert fingers strutting their

dazzling, even, stuff, style over

substance, I venture, won’t be

enough to whisk you into the

following centuries

Chopin, the other towering Romantic

figure standing between the spiritual

bookends of Beethoven and Brahms,

wrote two piano concertos, of which

his Second suffers from, essentially,

not being his First, however mighty

his Second here, for instance,

proves to be in this utterly convincing

performance, watch, wow

Beethoven, in other words, wrote the

book, two works, Tchaikovsky’s First

and Chopin’s First, tower above his

in the public imagination during the

ensuing High Romantic Period, after

which Brahms closes the door on the

era with his two powerful masterpieces

for piano and orchestra

of which more later

there are other piano concertos

along the way, but Beethoven’s

five, Tchaikovsky’s and Chopin’s

one each, and Brahms two are

the basics – but let me add, upon

further consideration, and for a

a perfect ten options, Liszt, his

own, of two, First Piano Concerto –

what you need to consider yourself

comfortably aware of the essentials

of music in the 19th Century, the

culture’s predominant voice then,

until art, painting, took over as the

Zeitgeist‘s most expressive medium

with Impressionism

of which more later

R ! chard

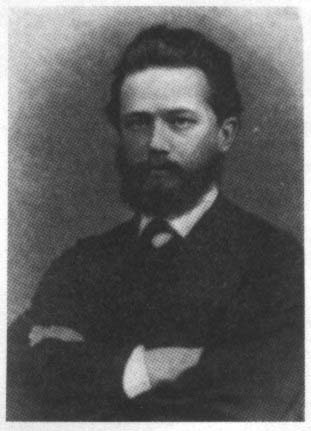

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1866)

______

for Elizabeth, who said she’d

“be all ears once it happens“,

this first of my Tchaikovskys

the example of Beethoven was

a hard act to follow, no one

nearby, which is to say, in the

vicinity of Vienna, which had

ruled the musical world for

more than half a century, from

Mozart to late Beethoven,

would be able to match his

eminence, not even the,

however mighty, Brahms

but in the East a star was born, in

1840, of extraordinary dimensions,

to tower above the High Romantic

period, which shone with, were it

not for its distance from the

European central galaxy,

comparable brightness

Beethoven had written for every

instrument, every combination

of instruments, every voice,

every combination of voices,

no other composer had, nor

has since, done that but the

incandescent Tchaikovsky,

who’d ever ‘a’ thunk it

symphonies, concertos, string

quartets, sonatas, variations,

ballets, operas, liturgical

pieces, there wasn’t anything

he didn’t touch, and transform

into magic

here‘s an early work, his Opus 13

only, in order to get chronological

perspective, and, as I pursue this

compelling trajectory, a sense of

his musical evolution, his First

Symphony, “Winter Dreams”*

listen for troikas flying across

the steppes, hear the bells tingle

from their fleeting carriages, be

swept away by the exhilarating

majesty

R ! chard

* Simon Bolivar Symphony Orchestra,

Joshua dos Santos, conductor

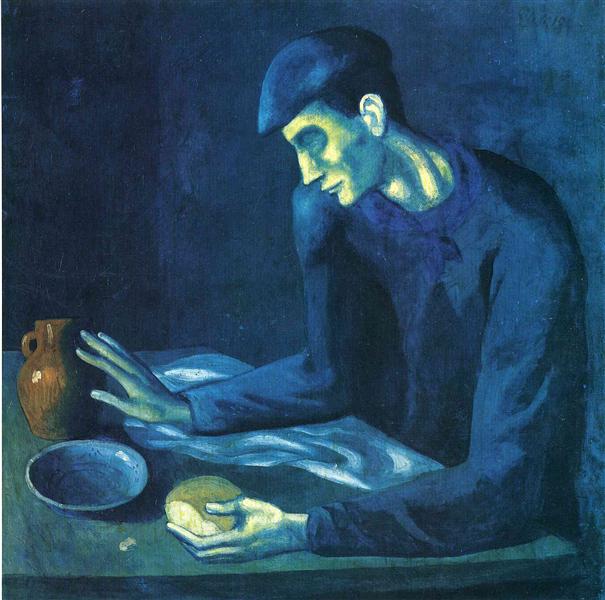

“Blind Man’s Portion“ (1903)

________

though you’ll have to actively listen

to Christopher King rather than

merely hear him here, as you might

have been doing with many of my

suggested musical pieces, should

you be at all interested in the history

of music, he is fascinating, dates his

investigations back millennia to very

Epirus, Ancient, nearly primordial,

Greece, to mirologia there, ancient

funerary chants

some have survived, and have been

recorded for posterity, one, in 1926,

by a Greek exile fled to New York City,

Alexis Zoumbas, a year later, however

improbably, by an American, a blind

man, his own story inspirational, akin

to that of Epictetus, one of the two

iconic Stoic philosophers, the other,

incidentally, an emperor, though the

blind man here, Willie Johnson, was

never himself a slave, but only, by a

historical whisker, the emancipations

of the American Civil War

Christopher King‘s comparison

of an Epirotic miralogi with an

American one brings up, for me,

the difference between Mozart

and Beethoven, notice how the

Willie Johnson version is more

rhythmic, the cadence is much

more pronounced than in the

Greek one, Johnson would’ve

got that from the musical

traditions Europeans had

brought over from their native

continent, probably also from

Africa, Africans

Beethoven would’ve been

surrounded, meanwhile, by Roma,

perhaps called gypsies then, their

music ever resonant in his culture,

not to mention later Liszt‘s, and

the Johann Strausses’ even, for

that matter, Paganini also seems

to have been imbued with it, it

having come up from Epirus

through, notably, Hungary – not

to mention, later still, that music’s

influence, and I’ll stop there, on

late 19th-Century Brahms

Christopher King, incidentally,

sounds a lot like someone you

already know, I think, from his

eschewing – Gesundheit – cell

phones, for instance, to his

enduring preoccupation with

death, not to mention his

endearing modesty, indeed

his humility, his easy

self-deprecation, despite his,

dare I say, incontestable, and

delightful, erudition

makes one wonder why that

other hasn’t become also

famous yet

what do you think

R ! chard