Just another WordPress.com weblog

Category: Beethoven

_____________

a trio is a group of three instrumentalists,

most often a piano, a violin, and a cello,

in our Western musical tradition

but it is also a musical form, like a waltz

is, or a prelude, or a nocturne, a trio is

a sonata, essentially, but written for

three instruments, not one, nor two,

consisting of more than one segment,

or movement

though I’ve presented trios as trios to date,

sonatas for three instruments, here’s a piece

for three instruments but in one movement,

though segmented, admittedly, as variations,

see above, a similar collection of rhythms

and styles, brought together by a common

essential element, a game audiences played

back then, and still do even now, trying to

distinguish the individual variations, before

falling prey to their enchantment

R ! chard

_________

the best way to sharpen your aesthetic pencil

is always to put one thing up against another,

then decide which you like best, the outcome

is never right or wrong, it is quite simply a

function of your aesthetic sensibility, the

more you exercise that taste muscle, holding

one element up against another, to compare,

the more you develop an informed, if not ever

conclusive, opinion, which develops eventually

into, if not authority, at least wisdom

what do you want to be when you grow up,

I asked myself in my very early teens, I

want to be wise like my grandmother, I

answered, have I reached my goal, you

tell me, though it is still, and ever will be,

my quest

Beethoven’s “Archduke“, also a trio, his

which do you like best, there is no correct

answer, but your choice will tell you a lot

about yourself

enjoy

R ! chard

________

Beethoven’s Opus 111 is, to my mind,

the equivalent of the Sermon on the

Mount, or Moses’s rendering of the

Ten Commandments, see above, in

our post-Christian world, the world

where God is dead and where we’re

all left to our own devices for better

or for worse

Beethoven confronts a Listener,

who is, or is not, there, pleading

for meaning, purpose

the first movement is rebellious,

despite, ever, his reverence for

his abstract Interlocutor, bowing

before, heeding, this self-anointed

Adjudicator, the Deity we fashion

for ourselves

we are witness to this interchange

the second movement is more

subservient, pleading more

rationally, less explosively, his

case, we hear this too

there are only two movements,

dichotomies, war, peace, man,

woman, chaos, order, none of

them a choice

Beethoven says to exist, to be,

itself, encompasses its own

glory, that is our grace,

whether or not there is a

hereafter

R ! chard

psst: thank you so much for your

participation, however

intermittent, in my Month

of Sonatas, I am not only

grateful, but honored, by

your presence

_______

from the very first few notes of Beethoven’s

we understand we’ve entered an entirely other

reality, the melody is unorthodox, not a lyric,

but, talking against the grain, the beat,

become a sentence, we are witness to

Beethoven addressing the infinite,

Beethoven at prayer, see above

the notes are clear, concise, naked,

happening, again, against the beat,

profoundly intimate, arhythmic,

unadorned, unadulterated, they are,

consequently, prophetic, not only

entertaining, but a moral code, a

metaphysical example of our role

in the shared fate of our nebulous

universe

Beethoven says we must believe

in our own beauty, our worth, it is

our only salvation

it is a mighty revelation

R ! chard

_______

we’re reaching the end of November, with

only three sonatas to go, which will be

devoted to Beethoven’s last three, they

exist in their import, impact, beyond

whatever’s been since, or before,

recorded

treatise on the physical possibilities

of a piano, its breadth of tonal range,

the scope of possible volumes, soft,

loud, not to mention its ability to, in

one instrument, play all the scales,

his following three sonatas, evolved

from the physical to the metaphysical,

“To be, or not to be”, he might as well

be asking, much like Shakespeare

there’d been metaphysical works before,

Bach’s cantatas, Handel’s Messiah, but

this metaphysics was of another order,

there’d been a revolution in France, the

Christian God had been there even

made illegal, Christians sent to the

guillotine, see Poulenc’s formidable

of that

Beethoven’s prayer, his evocation, in

his last three works for solo piano,

were to the Entity that might, or might

not be, out there, “To be, or not to be,

that [remained] the question”

the miraculous is that Beethoven, with

profound humility and respect, notes

that are clear, concise, and

straightforward, confronts the Entity

with nothing but his unadorned self,

at a loss in a sea of meaning, even

suffering despair, presenting, as an

argument the evidence of his life,

his art, his manifest and irrevocable

being, much as a flower would,

could it speak, no more, admittedly,

no less, but nevertheless a flower,

see above, and there is, Beethoven

says, glory in that

ponder

R ! chard

________

Johannes Brahms is pretty well the last of

the great Romantics, 1833 – 1897, he wrote

when he was not quite twenty, with the

same bravura as Beethoven, let me point

out, his sonata has five movements, a sign,

as I’ve said before, of bristling confidence

as a form grows from its original, pristine,

shape, it can only grow by evolving,

becoming something, eventually, that it

wasn’t, by dint of breaking all the rules,

transgressing

style becomes the manner in which a

work is transformed from its integral

state into something more decorated,

more intricately designed, like adding

lace to a perfectly adequate collar, or

making a soufflé out of an egg

but who wouldn’t, won’t

a point is reached where style overcomes

substance then, and becomes the focus

of the entertainment, one watches the

bravura

sonata, hasn’t the emotional appeal

that I’d heard in the earlier Romantics,

that would keep me rapt to the end,

the draw for me is the prestidigitation,

the manual dexterity, which is like

watching someone fly through the

air with the greatest of ease, but be

not otherwise moved, see above

but that’s me, and that’s to my mind

incidentally, since this is Brahms’

this is probably the last of the

great Romantic sonatas, after

which Impressionism

R ! chard

________

though there are other, and quite significant,

composers who fit into this category,

Beethoven, Schubert, and Chopin pretty

much define, all by themselves, the

Romantic Period

Chopin composed only two sonatas of note,

plus one more that is overlooked for being

an early, student effort, not up to the

standard of his later ones, Chopin, rather,

wrote mostly shorter pieces, nocturnes,

études, preludes, polonaises, and more,

that later became the very stuff of his

reputation

Schubert wrote enough sonatas that he

could be compared to Beethoven, indeed

it can be difficult to tell one from the other,

much as it can be difficult to tell Haydn

from Mozart, products in either case of

being both of their respective eras

when I was much younger, a guest among

a group of academics, where I’d been invited

by the host’s wife, a co-worker, what I knew

of Classical music, in the large sense, which

is to say comprising all of the musical periods,

Classicism, Romanticism, Impressionism,

and beyond, was all self-taught

is that Beethoven, I asked the host, about

a piece of music he’d put on

that’s Schubert, he replied, aghast, as

though I’d just farted

I blushed, deep red, confounded

Schubert, having great admiration for

Beethoven, took on many of the older

composer’s lessons, four movements

instead of the Classical three, for

instance, and many of the technical

tricks of his forebear

but there’s an essential component of

their styles that marks one from the

other, an easy way to tell them apart,

Beethoven always composes against

the beat, Schubert following it

listen to the first few notes of Beethoven’s

“Pathétique”, for instance, the beats are

erratic, confrontational, the mark of a

revolutionary, Beethoven was brashly

proclaiming his worth, he had something

to prove

Schubert, who was essentially playing

for friends, just wanted to entertain

them, which he did in spades, without

bombast or bluster

D959, for example, no swagger, no

ostentation, delivering nevertheless

something quite, and utterly,

enchanting, everything following,

unobtrusively, the beat

enjoy

R ! chard

_______

to say, I’ll try to make it clear and simple

first of all, hammerklavier is the German

word for piano, more specifically, klavier

means keyboard, hammer is a hammer,

what strikes the strings that make the

notes sound, rather than pluck them,

as in the harpsichord

the harpsichord had gone a long way, from

fortepiano to pianoforte, through to,

eventually, our modern piano

into his late stage, he’s not only telling

a story but delivering a thesis, on the

depth and range of the piano, not only

technically, structurally, but also

metaphysically, for that time

listen to the adagio sostenuto, the third

movement, Beethoven transports you,

moments after the first few notes have

been struck, into a meditation

adagios had been only emotional until

then, sentimental

this one’s a precursor to the adagio of

his last piano sonata, his no. 32, so

profound I want them to play it at my

funeral, it’s like looking in a mirror,

but more about that only later, maybe

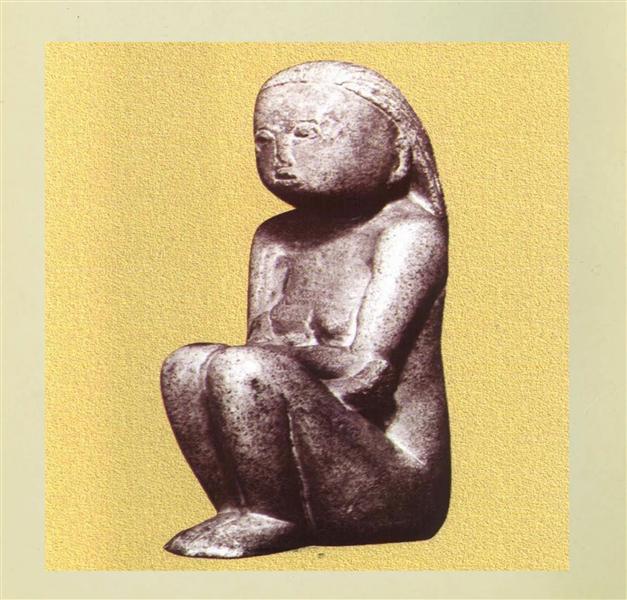

I remember turning a corner in the

Louvre – I’d been overwhelmed by

the quantity of works, stopped only

briefly before famous representations,

the “Mona Lisa”, for instance, more

historically interesting to me than

aesthetically, dusty, it seemed, with

age – and coming upon the “Venus

de Milo”, shimmering, breathing

apparently, see above, and being

transfixed forever

that someone, centuries ago,

millennia, could create something

so beautiful, so transcendent, so

timeless, full of grace, who’d have

someone, centuries later, be

mesmerized, made me believe

in beauty as a saving grace

this is what happened to me with

always happens

may this happen to you

incidentally, this version is the first

one I ever heard of the piece, a

gift from, if I may be indiscreet,

an Austrian lover, for my birthday,

way back when, the early Seventies

it has served me well

R ! chard

________

both have three movements, fast, slow,

fast, Beethoven still doing Beethoven,

each only about a year apart, 1804,

1805, listen to them side by side, from

movement to movement, the moods

in either are much the same

I’ll point out, however, that the second

are linked, there is no pause between them,

Beethoven is making clear that the sonata

is an integral whole, not a collection of

disparate elements

what does that mean, it means that

Beethoven is creating a literature, not

only tunes, but a story, with beginning,

middle and end

compare in art with the triptych, see above,

with artists delivering more than individual

paintings, but a narration

both arts, music, painting, are meant to

transcend their original ends

enjoy

R ! chard

______

Beethoven’s piano sonatas are divided in

three sections, Early, Middle and Late,

indeed, the last of his Early sonatas is

the early ones are all still highly influenced

by his illustrious predecessors, Mozart and

and Haydn, and derive, however

idiosyncratically, from the Classical Era,

though there are notable differences, his

addition of a fourth movement, for instance,

instead of the standard three, an upstart

strutting his stuff, asserting his potent

individuality

with the Middle sonatas, Beethoven is well

on his way to defining the Romantic Period,

nearly single-handedly, the works are bold,

expansive, lush, powerful, a story is told,

movements are chapters in a book, a book

of metaphysical dimensions

with the Late sonatas, Beethoven will leave

the planet, deliver musical revelations

compositional issues apply, which I won’t

get into, for being abstruse, but you can

already hear in his Middle sonatas the

powerful voice of a musical prophet

the name, it straddles the Classical and

Romantic Periods, at home in the salons

of the nobles, but dazzling as well for the

new audiences that are flocking to the

flourishing concert halls

and we’re only at the start of his Middle

Period

stay tuned

R ! chard