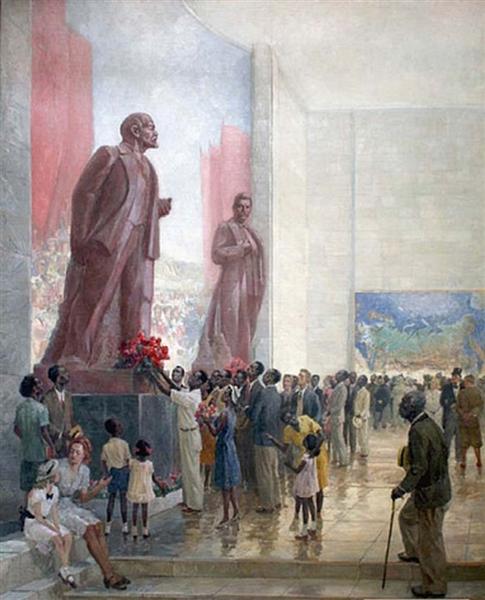

Symphony no 7 in C major, opus 60, the “Leningrad”- Dmitri Shostakovich

“Leningrad in blockade. Sketch on the theme of

“Leningrad Symphony” of D. D. Shostakovich.“

(c.1943)

__________

though I’ve been through the Seventh

three times already, consecutively, it

doesn’t reach, for me, the heights the

Fifth did, its first movement is

manifestly imperious, nearly even

overwhelming, certainly unforgettable,

I’ve been humming the ostinato in my

sleep

but the following movements seem to

me – not being Russian, nor having as

intimately incorporated their culture,

where rhythms and history are

inextricably intertwined – muddled

about the reconstruction of its

shattered world, melodies might be

lovely but are lost in a blur of musical

directions, there isn’t enough repetition

of musical motifs to find solid ground,

angry statements follow lyrical adagios

too often to get our bearings on what

might be going on

the first movement, however, remains a

triumph, note the debt owed to Ravel’s

“Bolero“ in the rousing ostinato, the

part where the same musical phrase

obstinately repeats its peremptory and

ever more vociferous mantra, its

headlong incantation, an interesting

blend in either symphonic work of the

sinuous, the seductive, the beguiling,

turning into the overtly martial, all to

do with pulse

the Symphony no 7, the “Leningrad”,

was first presented in that very city

during its siege by the Germans,

which lasted from 1941 to 1944,

however unbelievably, Shostakovich,

already a giant, was expected to deliver

a masterpiece by both the people and

by the regime, imagine Bono doing a

concert for Syria

Shostakovich doesn’t disappoint

players were culled from what remained

of instrumentalists among the survivors

of both Stalin’s criminal purges and of

the German siege itself left in the city,

those who hadn’t survived the famine

there, Valery Gergiev, an exalted

Russian conductor, describes them as

walking skeletons, meagre from

starvation, we’ve seen these before at

Auschwitz

the world heard, and was moved,

imperialism in any form was being

vociferously condemned, going back

to Napoleon even and his own failed

invasion, if not also to Hannibal

crossing the Alps, Caesar, his

Rubicon

much of this symphony is about cultural

resistance, the survival of a proud and

resilient seed, any proud and resilient

seed, hence its international standing

see Beethoven’s 9th Symphony for

comparable fanfare, flourish, and

circumstance, the only other work of

any such historical political importance

and, appreciably, still unsurpassed,

except for, maybe, Roger Waters

channeling Pink Floyd at the Berlin

Wall, along with, not incidentally

there, again Beethoven

R ! chard

psst: the other great composer of the

20th Century, Messiaen, also

composed a commemoration of

an awful moment in our history,

the Holocaust, his “Quartet for

the End of Time“, played originally

in his very concentration camp by

similarly “walking skeletons”, does

for me everything Shostakovich’s

Seventh didn’t