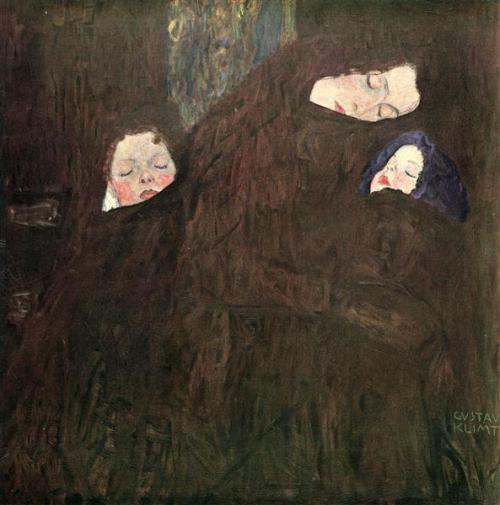

“Mother with Children” – Gustav Klimt

“Mother with Children“ (c.1909 – 1910)

_______

Gustav Klimt has long been one of

my very favourite painters, a large

reproduction of a detail of his

masterpiece, “Music“, hangs even

on one of my walls

how much is that Klimt in the

window, I’d asked the merchant

when I saw it from the street in

his shop’s display

later, I invited people over, to see

my Klimt, I’ve got a very large

Klimt, I’d say – this is before

anyone even knew of him, I was,

I’ll admit, a bad boy

around all that, I’ve had the good

fortune to see many of his works

during the several times I’ve been

to Vienna, where most of his

wonders reside, where they grace

that immortal city, the great hall of

the Kunsthistorisches Museum,

the Art History Museum in English,

for instance, the Beethoven Frieze

at the Vienna Secession Building

and, of course, at Belvedere, the

summer palace, where among

other paintings of his, you can

still see the iconic “The Kiss“,

their national treasure

but the painting above, part of a

private, apparently, collection, is

utterly new to me, and therefore

striking,

note how stark the background is

here, above, compared to Klimt’s

usually more ornamented

constructions, how the subject is

starkly the gentleness, the

intimation of peace, even serenity,

in the rosy cheeks of not only the

children, but of also the mother,

the slumber and surrender, midst

the imprecations of the

surrounding, and portentous,

darkness, note the paradoxical,

genetically determined even, trust

and love, in the consonant colours,

cherry blossoms blooming in all

three sleeping faces, despite the

threatening miasma of encroaching

and engulfing primordial earth

Shostakovich also said something

like that in his 15th String Quartet,

a fundamental harmony develops,

despite even strident distortions,

disturbances, in otherwise

unbearable situations, to provide

some solace, redemption

listen, I urge you, if you dare

compare the crook in the mother’s

neck, above, a nearly Baroque angle,

to the same docile, though resilient,

bent in Klimt‘s lover in “The Kiss“

for his provocative, maybe even

enlightening, perspective on

women

happy Mother’s Day, mothers, for all

your invaluable attention

R ! chard